![]()

Biographers and critics: Adolphe Jullien (1845-1932)

|

Biographers and critics: Adolphe Jullien (1845-1932)

|

|

Introduction

Adolphe Jullien’s career

Adolphe Jullien and Berlioz

Jullien on Berlioz: down to 1882

Jullien on Berlioz: 1888

Edmond Hippeau

Adolphe Jullien

Berlioz and Wagner

Jullien on Berlioz: after 1888

Illustrations

This page is also available in French

Débats = Journal des Débats

Hippeau 1883 = Edmond Hippeau, Berlioz intime (1883)

Hippeau 1890 = Edmond Hippeau, Berlioz et son temps (1890)

Jullien 1870 = Adolphe Jullien, Hector Berlioz 11 décembre 1803 – 8 mars 1869 (originally in Revue contemporaine, 15 March 1870, reissued in Airs variés (1877), pp. 1-64)

Jullien 1882 = Adolphe Jullien, Hector Berlioz. La vie et le combat. Les œuvres. (Paris, 1882)

Jullien 1888 = Adolphe Jullien, Hector Berlioz, sa vie et ses œuvres (Paris, 1888) (see review by Ernest Reyer, Débats 3 February 1889)

![]()

Berlioz died on 8 March 1869 at his home at 4 rue de Calais in Paris. Paradoxical as it may seem, his death marked the beginning of a revival in his fortunes as a composer, and within a decade many of his works were being performed with increasing frequency in Paris and attracting large and appreciative audiences. Among those who witnessed this revival and contributed to it was the writer Adolphe Jullien; subsequently and throughout his long career as a music critic, Jullien presented himself as an active champion of Berlioz, as well as of two other composers: Berlioz’s German counterpart Richard Wagner, and Robert Schumann, the three composers to whom he was most devoted. A number of Jullien’s writings on Berlioz have already been reproduced on his site in the original French, notably his pioneering study of 1870, which appeared within a year of the composer’s death, and extensive excerpts from the many articles he contributed to the Journal des Débats as its music critic over a long period of time from 1893 to 1928. This page presents a general view of Jullien’s work as a music critic, with particular reference to his work on Berlioz and his major publications on the composer.

![]()

The 1860s were the formative period of Jullien as a music-lover and concert-goer, and a major part in his early musical education was played by the Concerts populaires which Jules Pasdeloup founded in 1861. Subsequently Jullien never ceased to sing the praises of Pasdeloup’s pioneering venture, which for the first time made available to a wider public regular concerts of classical music at affordable prices. As well as spreading familiarity with the established classics — Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Weber, Mendelssohn — Pasdeloup actively promoted the music of young French composers — Gounod, Saint-Saëns, Bizet and others. Most strikingly he made a point of championing the music of the two most progressive and controversial composers of the day, Berlioz and Wagner. Pasdeloup was indeed, as Jullien put it, the ‘great musical educator of France’ who paved the way for the concert societies of Édouard Colonne and later Charles Lamoureux, who both learned from his example and eventually overtook him.

Jullien’s very first review appeared in November 1869 in the weekly journal Le Ménestrel and was, appropriately, of a concert by Pasdeloup that included a work by Berlioz, the overture le Roi Lear; it was signed simply ‘A. J.’. Over 30 years later, in 1903, Jullien referred back to that review nostalgically (Débats 22 November 1903). Two more reviews by Jullien of music by Berlioz appeared in the same journal the following year, this time with his full signature (16 January and 6 February 1870). Another Berlioz review by Jullien appeared in 1872 (14 January), this time of a concert at the Conservatoire, though this seems to have been his last extended Berlioz review for Le Ménestrel. A review in 1875 signed A. J. makes a brief comment on a performance of the second movement of the Symphonie fantastique (Le Ménestrel, 28 February 1875, p. 102), but that seems all:

The excerpt from Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, un Bal, was also successful; in it the waltz theme is developed with the opulence of orchestral writing which is found in all the works of the composer. [Signed A. J. i.e. Adolphe Jullien]

This is at first sight rather surprising: according to the regular listing published weekly at the top of every issue of the journal, Jullien was a contributor to it for a whole decade, virtually without interruption, from 27 March 1870 to 28 March 1880, and the 1870s were precisely the period when performances of Berlioz in Paris were multiplying rapidly. In practice it seems that after the early months of 1872 Jullien ceased to contribute regular reviews of concerts to Le Ménestrel. It seems also that during the 1870s Jullien wrote few original articles for the journal (none of them are on Berlioz), though the journal on its side gave him constant support. It frequently referred to his work for various other Paris journals (Revue et Gazette musicale, le Français, le Correspondant, Revue de France), mentioned some of his publications, and on several occasions reproduced excerpts or summaries of these (for example with his book Goethe et la musique in Le Ménestrel, 29 January 1880, p. 102). This pattern continued till early 1880, after which the journal ceased abruptly to refer to Jullien once he had dropped out of the roster of contributors. It does not seem, for example, to have made any mention of the publication in 1888 of his major work on Berlioz (see below) or to have published any review of it.

Many years later Jullien published a retrospective summary of his career as a music critic (Débats, 28 May 1922). In it he dated the beginning of his professional activity to May 1872 when he was entrusted with the regular music column in the daily journal le Français; he mentions casually his earlier contributions to other journals, Le Ménestrel, Revue contemporaine and Revue et Gazette musicale, but gives no prominence to his links with Le Ménestrel, as though this was a stage in his career that he did not wish to dwell on. Instead Jullien writes at length about his links with le Français, which evidently took up much of his attention in the 1870s and beyond. This continued until the journal merged with the older Moniteur Universel; Jullien does not specify at what date this took place, nor when he stopped contributing to it. Throughout the 1870s Le Ménestrel had made frequent reference to Jullien’s work for le Français with occasional citations from his articles, even though he was writing for a rival journal while being officially a contributor to the Ménestrel (for example 23 May 1875, p. 199-200; 15 April 1877, p. 153-4, where he is called ‘le critique musical du Français’). It is unfortunately not possible to trace the detail of Jullien’s contributions to le Français, since unlike Le Ménestrel and the Journal des Débats this journal has yet to be digitised and made available online.

Jullien contributed at various times to many other journals than those mentioned so far, such as the Revue d’art dramatique and le Théâtre. His other long-term association with a Paris daily apart from le Français was with the Journal des Débats; it began in 1893 and was to last till 1928, the longest tenure of the post of music critic in the history of that journal — his first article is dated 4 March 1893 and his last 15 January 1928. In all Jullien contributed well over 600 feuilletons to the journal, all of them published under the general heading Revue Musicale. As mentioned above, numerous excerpts from his feuilletons relating to Berlioz are reproduced on this site.

Jullien owed his position at the Débats partly to his own activities as a music critic for more than 20 years and the solid reputation he had established, and partly to the support of Ernest Reyer, a friend of Berlioz in his final months, a writer and composer in his own right, music critic at the Débats since 1866, and like Jullien an admirer both of Berlioz and of Wagner. Reyer had prepared the ground for Jullien’s entry to the Débats with appreciative comments on Jullien’s previous work (for example Débats 2 January and 11 December 1892), and frequent notices in the issues of 1893 mention explicitly that the Revue Musicale was henceforward to be shared between Reyer and Jullien (for example 28 February 1893 p. 3). The sharing continued for several years until 1898, with Jullien playing an increasingly large role, and from 1899 onwards he was in sole charge of the musical feuilletons.

In addition to contributing to many musical journals Jullien published a large number of books on a variety of artistic topics, starting in the 1870s with books on French opera in the 18th century. His 1888 book on Berlioz (see below) lists among his works to date (they are re-arranged here in chronological order of publication): La Comédie à la Cour (1875); Airs variés (1877, a collection of essays); La Cour et l’Opéra sous Louis XVI (1878); La Comédie et la galanterie au XVIIIe siècle (1879); Histoire du costume au théâtre (1880); L’Opéra secret au XVIIIe siècle (1880); Goethe et la musique (1880); La Ville et la Cour au XVIIIe siècle (1881); Paris dilettante au commencement du siècle (1884); Richard Wagner, sa vie et ses œuvres (1886). This is not a complete list; more publications were to follow later, including collections of essays, and they are too numerous to list here.

![]()

Jullien was still in his early twenties when Berlioz died, and though he had recollections of the composer in his later years he almost certainly never became part of his circle of close friends. His father, the linguist Marcel-Bernard Jullien (1798-1881) had a brief connection with the composer: in April 1867, aware no doubt of Berlioz’s interest in classical antiquity through the performances of Les Troyens à Carthage in November-December 1863, he sent the composer a copy of his just-published book Harmonie du langage chez les Grecs et les Romains. Berlioz’s letter of thanks is extant (CG no. 3230), and in his 1888 book on Berlioz Adolphe Jullien reproduced proudly a facsimile of another letter of Berlioz to his father two weeks later, in which he questioned him on a point of Latin pronunciation (Jullien 1888, p. 349; CG no. 3237). On a number of occasions Jullien related his memories of Berlioz in the 1860s (Jullien 1888, pp. 346-7; Débats 16 August 1903 and 9 March 1919). As mentioned above, his first experiences of Berlioz’s music came in the 1860s, mostly through Pasdeloup’s Concerts populaires, and on a few occasions through performances of excerpts of Berlioz at the Conservatoire (1861, 1863, 1864, 1865, 1866). He also attended some of the performances of Les Troyens à Carthage at the Théâtre-Lyrique in November-December 1863, though not the opening evening (Jullien 1870, p. 35; the same was true of his contemporary Georges de Massougnes, whom Jullien apparently never mentions). Curiously, he gained the impression that the performances had been a disaster and that the work had received a hostile reception, a view he kept repeating almost through his entire career, even though it is somewhat at variance with letters of Berlioz and evidence he himself cites (Jullien 1870 p. 21; Jullien 1882, pp. 10, 11, 33f., 43, 102; Jullien 1888 chapter 12, esp. pp. 285-94; and in later articles, e.g. Débats 16 October 1898, 16 August 1903). Jullien was able to catch glimpses of Berlioz himself on public occasions (such as concerts) and occasionally in private settings, such as with the Amussat family who were friendly with Berlioz. According to Jullien, the impression Berlioz conveyed most of the time was that of a sad and broken man who had almost given up the will to fight, and was to be regarded with pity. ‘Pauvre grand Berlioz’, ‘pauvre grand homme’, are phrases that recur with almost wearisome frequency in Jullien’s writings, down to his last feuilletons in the 1920s (for example Débats 20 July 1919, 4 April 1920, 2 October 1921, 1 October 1922). But this view of Berlioz was based on acquaintance with a man at the very end of his career who had been seriously ill for many years, more so than Jullien seems to have appreciated, and it hardly applies to his career as a whole.

In March 1870, a year after the composer’s death, Jullien published in the journal Revue contemporaine an extended study of Berlioz entitled simply ‘Hector Berlioz 11 December 1803 – 8 March 1869’. The study was meant to coincide with a celebratory concert on 8 March organised by the composer’s friend and champion Ernest Reyer. It was the first general study of Berlioz to be published since the composer had died, and sought to give an all-round view of his life, his music, the writer, and the man (the book on Berlioz by Georges de Massougnes, also published in 1870 and reproduced on this site in the original French, was not a biography and only covered part of his musical output). The full text of Jullien’s article is also reproduced on this site.

In assessing this work a number of allowances must be made. At the time of writing a great deal of information about Berlioz was either unpublished or not readily available (especially his correspondence). Much of his music had yet to become part of the regular concert repertoire. The work is not a full-length book but an extended article in four sections, each of which receives only summary coverage. The biographical outline is uneven, compressed in parts, and sometimes vague or inaccurate in chronology. And there are some sweeping and questionable assertions which call for more detailed argument if they are to be allowed to stand: for example ‘Berlioz’s music is rather difficult to understand because of the excessive complexity of his orchestration’ (p. 55); ‘Berlioz tried to extract more from music than it is able to express … he yielded too often to the urge to write descriptive and imitative music’ (pp. 56-7). Nevertheless, by making a stand on behalf of Berlioz at this particular time, so soon after the composer’s death, Jullien was pointing the way forward, and his defence of Berlioz was soon to be rewarded.

Twelve years later, Jullien published the first of his two books on Berlioz (Jullien 1882). The very short preface (pp. 7-8) does not explain the purpose of the work but merely states that the ‘real author of the book is the public’, that is, the concert-going public in Paris, who in the course of the 1870s had rediscovered the music of Berlioz and had come to appreciate it. The book is divided in two parts; the first is subtitled La vie et le combat and comprises seven chapters, and the second, called simply Les Œuvres, adds a further six chapters. These subtitles seem to imply that the first half of the book is biographical and the second is devoted to a study of the composer’s works. But this is not the case. Only the first chapter is biographical; it presents a very compressed summary of the composer’s life, which does not represent any advance on his 1870 article. From the second chapter onwards the whole of the rest of the book consists in practice of a series of review-articles which Jullien had written between December 1872 and December 1879, and which seem to be reproduced more or less as originally published. All but two of them (chapters 4 and 5 in Part I) are related to concert performances which took place during the 1870s in Paris, given by the concert societies of Jules Pasdeloup, Édouard Colonne and the Conservatoire, and which document the reception of Berlioz in Paris in the 1870s. In practice the chapters in both parts of the book treat at once of events in Berlioz’s life and of particular works. Jullien does not specify in which journal or journals the reviews were originally published; most probably it was in le Français, the journal of which Jullien became the regular music critic in May 1872 (see above). The book ends with a review of the concert performances of La Prise de Troie in December 1879, and there is no conclusion to pull the threads together or look forward to the future. Jullien does not give the impression that at that stage he was planning further work on Berlioz; he merely looks forward (in the preface) to seeing Wagner achieve the same recognition in Paris as Berlioz had now received.

Jullien’s next and largest book on Berlioz was altogether more ambitious (Jullien 1888), and this time Jullien provided a detailed preface to present the work. Unexpectedly, the preface begins not with Berlioz, but with Wagner. In 1886 Jullien published a large and lavishly produced study of Wagner entitled Richard Wagner, sa vie et ses œuvres (Richard Wagner, his Life and Works); this was the work that Jullien evidently regarded in 1882 as his next major objective as a writer: his ambition at the time was to see Wagner’s music gain the same recognition in Paris as Berlioz had. This in fact started to happen in the course of the 1880s, thanks to an important extent to the efforts of Charles Lamoureux and the concert society which he had founded in 1881. To Jullien’s satisfaction his book on Wagner was well received everywhere, and particularly in Germany. In writing the book Jullien claimed to have sought to reconcile his admiration for Wagner with the strictest critical impartiality; he was rewarded with the accolade of having written, according to an unnamed critic he proudly cites, ‘the first biography of Wagner that was truly worthy of the name’. The success of the book led to the demand that Jullien should do the same for Berlioz: Berlioz was the other great contemporary composer whom Jullien had been championing in his work as music critic. Apparently Jullien had not so far contemplated writing a large-scale study of Berlioz that would go beyond his works of 1870 and 1882, but the success of his biography of Wagner changed that. The new book appeared in 1888, a mere two years after the Wagner biography, which suggests that Jullien had already accumulated enough material to be able to complete the book in a relatively short period. It was dedicated ‘to my friend Ernest Reyer’, to whom Jullien had become close in the 1870s, and who went on to review the work very favourably a few months later (Débats, 3 February 1889).

According to Jullien’s Preface, there was as yet no proper full-length biography of Berlioz, and it was Jullien’s aim to fill that gap (p. IX). Jullien then proceeds to outline his own method: he starts from the assumption that Berlioz’s own Mémoires cannot be regarded as a trustworthy and truthful guide; they have to be tested and verified with evidence from contemporary newspapers, Berlioz’s own available correspondence (only a small part of which was published at the time), and the recollections of friends of the composer who were still alive. Two pages later (p. XI) Jullien corrects his own earlier statement: there did exist a large biographical study of Berlioz, by Edmond Hippeau (1849-1921), published in 1883 and entitled Berlioz intime (Hippeau 1883). (A second volume by Hippeau, called Berlioz et son temps, was written at the same time as the first volume, but only appeared in 1890 [Hippeau 1890] and was therefore not available to Jullien at the time.) Jullien praises the first book of Hippeau for its detailed research and the method he followed, and acknowledges his debt to him. Subsequently Hippeau is frequently cited by Jullien on points of detail, most of the time approvingly (pp. 9 n. 1, 16 n. 1, 31 n. 1, 52 n. 1, 67 n. 1, 72 n. 1, 112 n. 2, 134 n. 1, 158 n. 1, 170 n. 2, 298 n. 1). But Jullien then qualifies his praise: for all his valuable research Hippeau had failed to write a proper biography of the composer (see the full quotation below).

Hippeau, according to his own testimony (preface to Hippeau 1883, p. I), had started his detailed researches into Berlioz’s life several years earlier, around 1876. In both his books Hippeau was at pains to present himself as a devoted admirer of Berlioz (for example Hippeau 1883, pp. I, IV, 154-6, 490-3; Hippeau 1890, pp. 180, 400-3). Yet it is doubtful whether he should be enlisted among the leading Berlioz champions of his time, to be placed on the same level as, for example, Ernest Reyer and Julien Tiersot among critics and writers, or Édouard Colonne and Felix Mottl among conductors. It is noticeable how cool Ernest Reyer was towards both of Hippeau’s books. When the first book appeared in 1883 Reyer briefly mentioned its publication, calling it a ‘very interesting’ book which deserved a special study — but he did not have time for that at the moment (Débats 10 November 1883, p. 1). He only mentioned it again years later, first in the context of his review of Jullien’s 1888 biography of Berlioz, with which Hippeau’s earlier work was contrasted unfavourably (Débats 3 February 1889), then again two months later when it was reissued together with the publication of the second volume. Reyer dealt with both works in a few dismissive lines (Débats 14 April 1889).

One of Hippeau’s drawbacks is an effusive and self-indulgent style of writing which can easily discourage the reader. To quote an example from the concluding pages of his first book (Hippeau 1883 p. 490):

It is with tears that we, his friends in posterity, must address our last farewell to the man, we who love and understand him, we who to this day share beyond the grave the sufferings which tormented him, the baseness and iniquities which outraged the soul of this great artist.

Another major drawback is the lack of a clear and organised structure, which Jullien stigmatised in the first book (see the citation below). The work is divided into three parts which are only loosely chronological. Part I ‘The Man’ covers Berlioz’s early years up to 1827, when Berlioz’s life was changed when he first saw Harriet Smithson on stage at the Odéon theatre in the roles of Ophelia and Juliet; Part II ‘The Novel’ concentrates on Berlioz’s private life from that time up to the renewal of his relations with Estelle Fornier in 1864, and Part III ‘The Torment’ deals with the composer’s career, works and travels up to the time of his death; it therefore goes again over ground already covered in previous chapters, though from a different angle. Although writing at length about Berlioz and his life, Hippeau makes clear that he does not intend to write a formal biography, but is interested primarily in pursuing a ‘psychological analysis’ of the composer (pp. 4, 23, 43f., 363, 388). Another quotation will illustrate the point and bring out the drawbacks of Hippeau’s chosen approach. At the start of chapter XXII Hippeau notes (p. 409):

While following Berlioz in his political digressions [in chapters 58-59 of the Mémoires] to find out about his impressions, I have skipped over the detailed incidents of his career from 1848 to 1852. Chronology is of no significance here, and besides, I am not writing Berlioz’s biography.

While Hippeau’s second book is meant to be complementary to the first one and deal with Berlioz the musician and his works, there is no need to discuss it in detail here: it had no influence on Jullien’s 1888 book, and in any case shares the same characteristics and faults of the first book. Nevertheless, Hippeau is a significant figure in the history of Berlioz studies in France, and deserves some discussion because of the influence he exercised on subsequent writers, as Jullien himself acknowledges:

It was Edmond Hippeau who was the first to have the idea of checking in minute detail the narrative of the Mémoires against the private correspondence of Berlioz; the first, thanks to intelligent research, to have thrown unexpected light on certain episodes which were shrouded in tactful obscurity, as Berlioz wanted. […] I must declare here how valuable the voluminous work of M. Hippeau has been to me, even though he neglected, apparently out of weariness, to give his work the shape and tone of a coherent and well organised biography.

Thus Jullien in the introduction to his own biography of Berlioz (Jullien 1888, p. XI). Berlioz’s Mémoires, though completed in 1865, were first made available to the general public in 1870 after the composer’s death. The work was extensively reviewed by Ernest Reyer in the Journal des Débats the following year (15 and 16 March, 4 and 5 June), but his review was simply an extended summary of the contents of the work and did not raise the question of its truthfulness and accuracy. Jullien’s earlier works on Berlioz (Jullien 1870 and Jullien 1882) similarly did not express any critical view on the use of the Mémoires as a source for Berlioz’s life. This changed with his 1888 biography, and as Jullien acknowledged, it was Edmond Hippeau who was the first to subject the Mémoires to critical scrutiny. While this approach was in itself not only justifiable but necessary, it had the effect of casting Berlioz in an unfavourable light: it gave rise to the view that Berlioz was something of a poseur who, despite his repeated claims for the accuracy and truthfulness of his Mémoires (see the page on their composition and history), had sought to create an idealised view of himself through his autobiography, in which he deliberately suppressed or distorted episodes in his life which were not to his credit. This approach gained widespread currency: it influenced Jullien himself in his 1888 book and in his subsequent writings on Berlioz. Its most zealous proponent was Adolphe Boschot, who in his 3 volume biography of Berlioz developed an unflattering picture of Berlioz as a weak and vacillating character, a picture which was difficult to reconcile with what Berlioz the creative artist had actually achieved. Jullien was later to review Boschot’s three volumes (1906, 1908, 1913), but though he objected to Boschot’s style and the spirit in which he wrote his work, he nevertheless shared with Boschot a common distrust of the Mémoires, which had its origin in the work of Hippeau. Berlioz studies in France had to wait till Julien Tiersot to find a voice that started from the opposite assumption, and was prepared to defend the essential accuracy and truthfulness of the Mémoires.

Jullien was influenced by Hippeau, not just on matters of detail but in his view of Berlioz the man, and he acknowledged his debt to him. Hippeau on his side was consistently complimentary towards Jullien and his work: he praised him in the preface to his first book, and his second book was dedicated ‘to my eminent colleague and friend Adolphe Jullien, who was the first to have worked to glorify the master [Berlioz], and who knows like me how great he is compared to the small masters of the present’ (Hippeau 1890, p. V; Jullien’s 1888 book is also referred to approvingly on pp. 328-9).

It should be added that Jullien’s own work was on a higher level than that of his predecessor; it was better written and more concise, and more clearly organised. In his review of Jullien’s book Reyer described it as ‘the most complete, and I would add the most authentic biography that has been written on Berlioz, without excepting the one published a few years ago by M. Edmond Hippeau’ [Hippeau 1883]. The first impressions of anyone who picks up the book are likely to be positive: this was by far the most attractive-looking book on Berlioz that had been published to date, and it remains to this day something of a collector’s item. The book is in a large and imposing format (21 x 32 cms), it is beautifully printed, and lavishly illustrated with a profusion of contemporary portraits, engravings and drawings (there is a detailed listing of these on pp. 381-4). These include 14 original engravings illustrating the life and works of Berlioz by the artist Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904), a personal friend of Jullien; he had provided a similar set of engravings for Jullien’s 1886 book on Wagner, and had painted what appears to be the only known portrait of Jullien. (For Fantin-Latour’s Berlioz engravings see the section on this site Berlioz-inspired works of art). One of the original features of the book on which Jullien prided himself was the inclusion of a large number of cartoons of Berlioz from the contemporary Paris press, which span Berlioz’s career from the 1830s down to the 1860s and give a satirical perspective on how Berlioz was perceived in Paris.

Despite the lavishness of the presentation a few reservations are in order. The book has no general index, and a chronological chart of the main dates and events in Berlioz’s life and career would have been of assistance to the reader. Also, Jullien did not include a bibliography; he does not mention his own previous writings on Berlioz, not even his 1882 book from which he adapted substantial excerpts concerning Berlioz’s musical works; these were derived ultimately from his reviews of concerts in the 1870s (for example pp. 92-4 on Harold en Italie, 104-5 on the Requiem, 136-42 on Roméo et Juliette, 190-5 on la Damnation de Faust, 226-8 on l’Enfance du Christ, 269-75 on la Prise de Troie and 278-84 on les Troyens à Carthage).

The largest part of the work is biographical. The first thirteen chapters (out of a total of sixteen) chart the life and career of Berlioz in detail, with pauses in the narrative to present and discuss at the appropriate place his major works. Surprisingly Béatrice et Bénédict, his last major work, is discussed in chapter 11 before les Troyens in chapter 12, presumably on the grounds that it received its first performance before the Virgilian epic, but this obscures the fact that the composition of les Troyens started in 1856, a fact not mentioned in its proper chronological place on p. 239 and which only emerges much later when Princess Sayn-Wittgenstein is suddenly introduced (p. 263). After the narrative part of the work chapter 14 deals with Berlioz the artist and creator, chapter 15 with the critic and the man, and the final chapter 16 covers the posthumous revival of interest of the composer after his death up to the inauguration of the Berlioz statue in Square Vintimille in 1886 and the restoration of his tomb in Montmartre cemetery the following year.

It would be tedious to attempt to discuss at length the many points that the book raises, but a few general observations may be made.

First, the focus of the book seems rather too much concentrated on Paris. Paris was indeed the centre of Berlioz’s career as a composer, writer and music critic; he kept returning there despite the very ambivalent feelings he had towards the capital city, and though he was presented at various stages of his career with a number of opportunities to settle abroad he never took these. Berlioz’s many travels abroad figure of course extensively in Jullien’s biographical narrative, but their significance in his career and in the wider history of nineteenth century music is not clearly brought out. For example, although Berlioz wrote little music during his stay in Italy, his experiences of the country, its people and its landscapes left a permanent impression on him, and these were to bear fruit in many of his subsequent works, from Harold en Italie via Benvenuto Cellini, Roméo et Juliette and les Troyens down to Béatrice et Bénédict. Curiously the author fails to bring this out (p. 71). The same applies in various ways to his subsequent travels abroad. It is noticeable that though the book is lavishly illustrated, the illustrations centre mostly around Berlioz’s career in Paris; an opportunity has been missed to give a visual commentary on his travels abroad, from the landscapes and monuments of Italy, to his many travels in German lands, to Russia and his repeated visits to London. There are no illustrations, for instance, of the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London which impressed Berlioz so much, and his trip there to serve as a juror in judging musical instruments submitted at the exhibition receives only the most cursory mention (p. 214).

A second observation concerns Adolphe Jullien as a musician. From an early age Jullien was a keen music-lover who became very knowledgeable on the history of music, and had a wide range of musical interests apart from his special fondness for the music of Schumann, Wagner and Berlioz. But Jullien was not a practising musician: he was not a performing virtuoso or instrumentalist, nor a singer, nor a conductor, and was not a composer either (unlike his mentor Ernest Reyer). This lack of direct personal experience of music-making shows up in his book. In his discussion of individual works, whether in this book or in his other writings, Jullien never makes use of musical examples to guide the reader. His detailed descriptions of particular passages or movements are sometimes difficult to match with the printed score (for example on p. 78, in relation to the fourth movement of the Symphonie fantastique, he confuses drums (tambours) with timpani (timbales), and attributes to the piccolo the reminiscence of the idée fixe which is in fact played by the clarinet). Berlioz was not just a great composer but an eminently practical musician. Early in his career he started to befriend instrumental players, learn from them about their instruments and apply that knowledge in his compositions. Later he became friendly as well with instrument makers such as Jacob and Édouard Alexandre, and Adolphe Sax, and showed a keen interest in their experiments with new instruments. With no pre-existing models to follow he also taught himself the art of conducting virtually single-handed, and developed an effective technique of sectional rehearsals which served him well throughout his career. In the 1840s and 1850s he was thought by many to be the finest conductor of his time. None of this receives any discussion in Jullien’s book. Berlioz’s treatise on orchestration is only mentioned casually, with no indication of its historical significance (p. 168), and while the merits of Berlioz as an orchestrator are extolled in general terms (for example pp. 330-1) there is no examination of the ways in which Berlioz advanced this particular branch of the craft of music. The chapter on the art of the conductor, which Berlioz added to the 1855 edition of the treatise on orchestration, is merely listed among his works but not discussed in its own right (p. 380). An important dimension of Berlioz’s achievement does not receive the treatment it deserves.

Thirdly, and paradoxical as it may seem, it could be argued that Jullien was not in practice wholly in sympathy with Berlioz, much as he may have championed him and his music throughout his career. There is in Jullien a censorious streak which he shares with Edmond Hippeau. As seen above, Hippeau repeatedly proclaimed his devotion to Berlioz, but claimed at the same time the right to seek out the truth, and expose where necessary Berlioz’s weaknesses and shortcomings (as he saw them). Though he does so with greater restraint than Hippeau, Jullien pursues a similar approach; he prides himself on his impartiality, exemplified by his willingness to criticise where appropriate Berlioz, both the man and the artist. Hippeau was critical of Berlioz the man, but on the other hand effusive in his praise of the artist, and drew here a contrast between his first and his second books; according to him, some thought he was too critical of Berlioz in his first book on Berlioz the man, but they may now think that he is too generous in his second book on Berlioz the artist (Hippeau 1890, pp. III-V). Hippeau claimed in that book that it was Berlioz, and not Wagner, who was the true innovator in nineteenth century music, whereas Wagner had merely appropriated what the French composer had originated.

Jullien on his side is ambivalent in his views of Berlioz the man, and in this he is influenced by the approach of Hippeau to the Mémoires. But he can also be equivocal in his pronouncements on the artist and on works which he professes to admire. For example, in relation to the Te Deum Jullien claims that Berlioz ‘dreamt of composing works that were ever more grandiose and noisy’ (p. 234). The idea is picked up again later: ‘Berlioz never cured himself of his obsession with huge orchestras and monster festivals’ (p. 324). The charge is then developed at length, only to be abruptly contradicted with the statement: ‘Surprising as it may seem, Berlioz detested noise in music’ (p. 326). In writing Harold en Italie ‘Berlioz yielded too much to his taste, I might even say his mania, for depicting in sound the most diverse episodes of real life’; in trying to introduce a prominent part for solo viola in a large orchestral work Berlioz was ‘attempting the impossible’, but all the same he displayed in the work ‘his usual wealth of imagination and wonderful understanding of orchestral sonorities’ (p. 92). In his discussion of the Requiem Jullien uses the adjective ‘bizarre’ to characterise the work (‘the Kyrie is one of the least bizarre and most expressive movements’ of the work), though as a whole the Requiem ‘is a creation of genius’ (pp. 104-6). In writing Béatrice et Bénédict as Berlioz the composer is said to have been in contradiction with Berlioz the critic, who had decried many an opéra comique he had reviewed, though the work itself ‘is one of his most exquisite scores’ (p. 254).

Jullien’s conception of Berlioz the man is of a personality that was impetuous, impulsive and overwrought. Berlioz, for example, composes la Damnation de Faust ‘in his usual state of frenzy’ (p. 183). There is little acknowledgement of the other side of Berlioz, rational, objective and analytical, a man who was capable of seeing himself and his own work with cool and critical detachment, and of pursuing his long-term objectives with patience and tenacity. For instance, Berlioz wrote the Huit scènes de Faust in 1828 under the immediate impression of Goethe’s poem and published it without delay, but then withdrew the work and only returned to the subject many years later, in 1845-1846, when he was ready to tackle it to his satisfaction; the full score of la Damnation was only published in 1854. Similarly he composed the Symphonie fantastique in 1830, but then revised the work extensively during his stay in Italy and only allowed the score to be published as late as 1845.

For Jullien, Berlioz was a ‘romantic’ through and through. This view is developed in the chapter on Berlioz the artist and creator (pp. 317-34), in which Berlioz is systematically characterised as ‘romantic’: ‘Berlioz was not only romantic in his literary aspirations and his artistic refinements … he was romantic to the core and remained so all his life, in every sphere of his activity, in his compositions, in his writings, in his letters, and in his loves’, and so on at length (p. 318). The all-purpose word ‘romantic’ is assumed to be self-defining and all-explaining. It also carries a pejorative colouring: ‘romantic’ is often taken to be synonymous with ‘extravagant’ or ‘excessive’. But it is easily overlooked, as has been pointed out by P.-R. Serna (Berlioz de B à Z [2006], p. 183), that the words ‘romantique’ and ‘romantisme’ were not used very often by Berlioz. Most important, they are words that Berlioz did not apply to himself or to his music (see for example how he characterises his own style and musical tendencies in the Post-Scriptum of the Mémoires). All this can be verified with a word search through his writings and his feuilletons. Yet the words are constantly applied to Berlioz, as by Jullien in 1888 and others later: Adolphe Boschot defined Berlioz as a ‘romantic’ in the title of each of the three volumes of his biography of the composer.

Having characteristed Berlioz as a romantic to the core, Jullien then qualifies this elsewhere in his book with a different view of Berlioz: he identifies in Berlioz two conflicting tendencies, the ‘classical’ versus the ‘romantic’ (pp. 270, 333). Berlioz started off as a ‘romantic’, influenced primarily by Weber and Beethoven (with the Symphonie fantastique and his works of the 1830s and 1840s). He then returned in the 1850s and 1860s to a ‘classical’ style, where the predominant influences were Gluck and Spontini (with l’Enfance du Christ, les Troyens and Béatrice et Bénédict). It may be wondered whether these simple labels characterise adequately individual works. Berlioz’s four symphonies, composed between 1830 and 1839, are all very different from each other, and each of them is full of contrasts between their different movements; it is of little use simply to label them all as ‘romantic’. Are the Nuits d’été of 1840-1841 to be described as ‘romantic’? If the Requiem of 1837 is ‘romantic’ (p. 104), how should the Te Deum of 1848-49 be described? What all of this overlooks is Berlioz’s lifelong search for novelty and variety in his output: each new work had to be different from its predecessors and break new ground. As for l’Enfance du Christ it may be worth citing Berlioz’s own comments (Post-Scriptum of the Mémoires):

A number of people thought they could detect in this score a complete change of style and manner on my part. Nothing is further from the truth. The subject naturally called for music of a naïve and gentle kind […] I would have written l’Enfance du Christ in exactly the same way twenty years ago.

Jullien thought of himself as championing equally the two great contemporary composers Berlioz and Wagner, and his two largest books were devoted to each of the two, though written in the reverse order, Wagner first then Berlioz. It might be argued that Jullien was more naturally in tune with Wagner than he was with Berlioz. In his 1888 book he drew an elaborate contrast between the two, which was to the advantage of the German over the French composer. In so doing he came to a conclusion that was the opposite of Hippeau’s in his 1890 book.

In Jullien’s view, Wagner pursued single-mindedly and from an early date a well-defined ideal, the fusion of drama with music, and brought musical drama to the highest degree of perfection it could achieve. Berlioz on his side had grasped all the changes he thought could and should be made to the symphony and to opera, but did not aim at a comprehensive reform of either. Berlioz was not consistent with himself: he assigned to the symphony a much more complex role than was normally assigned to it, yet pretended to respect established forms; he sensed that opera was capable of reaching a much higher degree of dramatic truth, but believed this could be achieved without modifying the traditional forms. In short he was trying to conciliate the irreconciliable: whether he was writing a mass, a symphony, an overture or an opera, he wanted to stay within the conditions of pure music, yet at the same time he wanted to compose music that was in the first instance expressive. By extending musical forms which were not susceptible of indefinite extension, he ran the risk of subverting the art of music, while believing he was simultaneously enriching and consolidating that art. Hence Berlioz failed to conceive the new art that was to be born from the fusion of poetry and music; and yet, without being aware of it, he sowed the seeds which were to bear fruit in the works of Wagner.

This is a necessarily compressed and simplified summary of a longer passage (pp. 326-8). Whether it fairly represents Jullien’s argument; whether it gives an adequate summary of Berlioz’s varied achievement; whether Berlioz was mistaken in refusing to formulate a coherent ‘system’ of his own and implement it in his works; and whether Wagner’s music dramas should be thought of as the ultimate destination of nineteenth century music — these are questions that may be left for the reader to decide.

The scale of Jullien’s 1888 biography of Berlioz and the prestige of its author ensured that it would enjoy lasting status. No comparable work was published in France during the decade that followed. When in 1904 Julien Tiersot published his Hector Berlioz et la société de son temps, he specified that this was not a biography but a thematic study, and he professed himself satisfied with Jullien’s existing work. It was not till after the centenary of Berlioz in 1903 that other critics were encouraged to publish large-scale biographies of the composer, first Prod’homme in 1905, then Boschot in his 3 volume work (1906, 1908, 1913) which surpassed Jullien in its scale and attention to detail.

The 1888 biography was the largest work Jullien had published on Berlioz so far, but it was also the last extended work he devoted to the composer. Although he continued to publish on Berlioz for many years to come, it was on a smaller scale and he did not attempt to break new ground. Jullien did not apparently think of ever issuing an updated or revised edition of his work, such as a more concise version without the numerous illustrations. He ended the 1888 biography on a note of finality, with the inauguration of the statue of Berlioz in Square Vintimille in Paris (17 October 1886) and the restoration the following year of the composer’s tomb in Montmartre cemetery (8 March 1887). The great man had finally achieved official recognition in the capital of France which had long disdained him, and could now rest in peace. It is as though Jullien felt that his own work was now complete and did not need adding to. There is no suggestion in the book that there remained a great deal of research to be done on Berlioz, and that new material would continue to be discovered and published; Jullien made no attempt to sketch out lines of enquiry that future Berlioz scholarship might pursue.

What Jullien did continue to contribute, for many years to come, were shorter articles, above all the long series of feuilletons which he wrote for the Journal des Débats from 1893 till 1928, at first down to 1898 together with Ernest Reyer, then on his own thereafter. Most of his feuilletons relating to Berlioz are reproduced in the original on this site.

A very large number of these feuilletons consist of longer or shorter reviews of performances of Berlioz’s music in Paris. These concern only a small proportion of those performances that took place, as Jullien was naturally very selective in which concerts or performances he would review. By the time he became a contributor to the Débats the music of Berlioz was firmly established in the regular repertoire of Paris’ concert societies, and performances of some works — above all the very popular Damnation de Faust — were unexceptional. Hence Jullien normally concentrated on works or performances that were more noteworthy, such as the Requiem (1894, 1900, 1912, 1914, 1925), the Te Deum (1895, 1905), la Prise de Troie (1898, 1899), l’Enfance du Christ (1908, 1909), Benvenuto Cellini (1913), or les Troyens (1921). He occasionally singled out special occasions, such as the 100th and 150th performances of la Damnation at the Colonne concerts (1898 and 1907), or concerts conducted by celebrity German conductors in the pre-1914 period, such as Felix Mottl (1897, 1898, 1899, 1909) or Felix Weingartner (1898, 1901, 1905, 1906). In many of these cases the comments made by Jullien about the works themselves frequently echoed, sometimes word for word, what he had written about them many years earlier: the reader may recognise in them passages that are taken from reviews originally written in the 1870s and already reproduced in his 1882 book. Jullien’s views on all Berlioz’s works were formed early in his career, in the 1870s and early 1880s, and did not change thereafter.

One work, however, was new to Jullien in his period as critic of the Débats, and had not been dealt with by him previously: la Damnation de Faust — not the original work itself, of course, but its adaptation for the stage, which was due to the impresario Raoul Gunsbourg, director of the Monte-Carlo opera house, where he staged it for the first time in 1893. Jullien, following in the steps of his mentor Ernest Reyer, took strong exception to this arrangement of a work that Berlioz had intended for the concert hall. He attacked the idea in his very first feuilleton for the Débats in 1893 and frequently returned to the subject (1902, 1903, 1910, 1921), even taking issue publicly with the heirs of Berlioz (the Chapot family) in 1902 for sanctioning what he regarded as a travesty. To his great regret, the staged version of la Damnation became very popular and in the 1920s even supplanted in popularity the original concert version of the work.

Apart from performances Jullien also reported on Berlioz-related events of note, most important of which were the celebrations in 1903 for the centenary of Berlioz’s birth abroad and in France (Grenoble and La Côte Saint-André, as well as Paris). Of more personal interest is his account of a visit to the tomb of Berlioz at Monmartre cemetery in 1902, which echoes the concluding chapter of his 1888 book, as do later his memories in 1919 of Berlioz’s last years, published on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Berlioz’s death.

Jullien’s feuilletons comprise also a large number of book reviews; these often appeared during the summer months, in the interval between the end of one concert season and the start of the next. Reproduced on this site are several reviews of some of the most important Berlioz publications of this period, notably by Julien Tiersot (1904, 1907, 1919), J.-G. Prod’homme (1905), and Adolphe Boschot (1906, 1908, 1913, 1920). Jullien was always scrupulously fair in acknowledging the work of his colleagues, yet his reviews do not convey the sense that he felt that they added anything more than interesting footnotes to existing Berlioz scholarship. For his part he had reached his own conclusions on Berlioz many years earlier, he was now regarded as the ‘Doyen of Berlioz scholars’ (Débats, 15 August 1920), and did not see the need to change his mind.

One illustration of this attitude is his reaction to the question of a new edition of Berlioz’s music. The desirability of a new and complete French edition of Berlioz’s musical works was raised in an article by André Hallays in the Journal des Débats (12 September 1902) concerning the centenary celebrations planned in Grenoble for August 1903. Hallays was quoting there a letter of G. Allix to the committee organising those celebrations. Two days later Jullien dismissed the idea (Débats 14 September 1902): a complete edition was already in progress in Germany (the Breitkopf edition by Malherbe and Weingartner), hence a competing French edition would be superfluous. Besides, copyright rules in France made such an undertaking impossible until 50 years after the death of the composer (i.e. March 1919), whereas in Germany copyright expired only 30 years after Berlioz’s death, and Breitkopf & Härtel were at liberty to start publishing a new edition in Germany to coincide with the composer’s centenary in 1903. Jullien returned several times to the question (Débats 28 September and 26 October 1902; 16 August 1903). In a review of a concert in 1906 he referred to the ‘absolutely complete and perfect edition’ of Berlioz’s works, published in Germany and edited by Charles Malherbe and Felix Weingartner (Débats 6 May 1906).

The praise was premature: the edition was not complete at the time and several volumes were still to be published. Malherbe was to die in 1911; Jullien does not seem to have mentioned his death in his feuilletons, though earlier that year, in a review of a book on Auber (Débats, 23 July 1911), Jullien had warmly praised Malherbe’s ‘great concern for precision and his constant recourse to unpublished documents, and the great warmth of spirit which he displays in all his writings and which make him much more inclined to praise than to criticise’. With Malherbe’s disappearance the Breitkopf edition of Berlioz was left unfinished, and Weingartner made no further contribution to it. The two operas Benvenuto Cellini and les Troyens were the most conspicuous absentees from the edition. On the occasion of the half-centenary of Berlioz’s death in March 1919 Jullien contributed an article of reminiscences about Berlioz, but said nothing about reviving the plan for a French edition, at least for the two missing operas, and never returned to the subject subsequently. As for the ‘perfection’ of the Breitkopf edition, one wonders what Jullien’s opinion was based on, particularly since the Breitkopf edition was not available in France at the time. It was left to Tom Wotton to question its merits, first in an article published during the war, in 1915, and later in his 1935 book on Berlioz.

![]()

Throughout his career Jullien was consistent in his championship of Berlioz, and it mattered to him that the composer should receive recognition in his own country, and not just abroad: this is the guiding thread of so much that he published on Berlioz. It mattered to him that Berlioz was a French composer and should be thought of as part of the national heritage. Although free from any suspicion of chauvinism — Jullien was equally sincere in his championship of Wagner and of Schumann — he constantly referred to Berlioz as ‘notre grand Berlioz’, just as Rameau was ‘notre grand Rameau’ (see the feuilletons of 16 August and 20 December 1903; 17 January 1904; 7 May 1905; 12 May 1912; 4 April and 15 August 1920; 1 April 1923). In this he reflected attitudes that were common not just in France, but throughout Europe in the late nineteenth century, and were shared by many of his contemporaries, for example Octave Fouque, Charles Malherbe, and others. Edmond Hippeau thought of Berlioz as the ‘leader of the French national school’ (Hippeau 1883, pp. 2-3; Hippeau 1890, pp. 140, 399-400). Berlioz would have been doubly surprised: he did not present himself as a specifically French composer and once described himself as ‘three-quarters German’ (Débats, 9 February 1860, reproduced in À Travers Chants); he did not either think of himself as leader or founder of any particular ‘school’, but declared rather his allegiance to ‘the religion of Beethoven, Weber, Gluck and Spontini’ (Mémoires, Post-Scriptum).

Among champions of Berlioz in France in the period before and after the first World War Jullian holds a significant place. He both witnessed and contributed to the Berlioz revival that blossomed after the composer’s death. His 1888 biography was an important milestone in Berlioz studies, but it had its limits and was eventually overtaken by the work of others. Of special importance was the work of Jullien’s younger contemporary Julien Tiersot, whose series of Berlioziana studies explored new areas of Berlioz scholarship, and who was also the first to conceive and begin to implement the project of collecting the complete correspondence of the composer. Jullien praised the work of Tiersot — but he had not thought of undertaking himself what his younger colleague did.

![]()

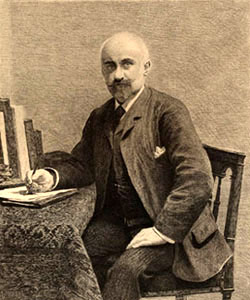

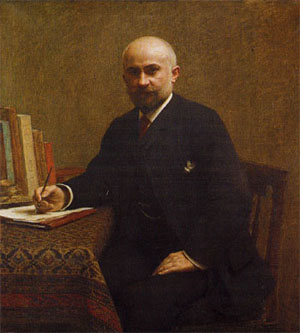

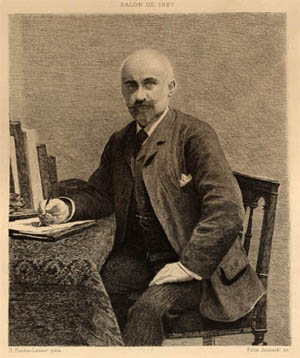

The original copy of this portrait by Fantin-Latour (1836-1904) is in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, reproduced here courtesy of Jean-Jacques Lévêque, Henri Fantin-Latour (ACR Edition, 1996). This appears to be the only extant portrait of Adolphe Jullien. Surprisingly, there do not seem to be any known photographs of him; did Jullien refuse to be photographed?

This 1887 engraving by Félix Jasinski (whose exact dates are unknown) was created after Fantin-Latour’s painting displayed above.

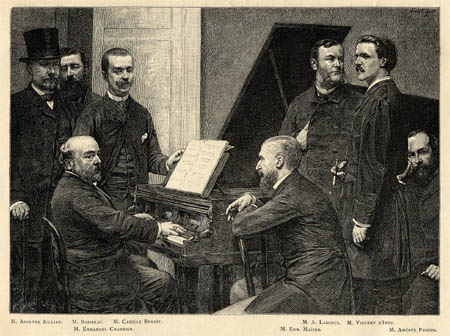

The above 1885 painting, also by Fantin-Latour, depicts a group of friends sitting around a pianist, the composer Emmanuel Chabrier (hence the title by which the painting is known). The friends are writers, and professional and amateur musicians; they are, from left to right, Adolphe Jullien (in top hat, holding a cane), Arthur Boisseau, Camille Benoît, Antoine Lascoux, Vincent d’Indy, Edmond Maître and Amédée Pigeon. Fantin-Latour presented the painting at the Salon de 1885. This appears to be the only representation of Adolphe Jullien apart from the portrait by Fantin-Latour reproduced above. Strikingly, Jullien’s face is obscured under his hat, whereas the faces of all the other persons present are brighter (and none of them wears a hat). The original painting is in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, reproduced here courtesy of Jean-Jacques Lévêque, Henri Fantin-Latour (ACR Edition, 1996).

This engraving, by Thirat after Fantin-Latour’s painting above, was published around the same time in an 1885 issue of Le Monde Illustré, reporting on Fantin-latour’s latest paintings. At the time Adolphe Jullien was one of the contributors to the paper, and in the text accompanying the engraving is referred to as notre confrère [our colleague].

|

|

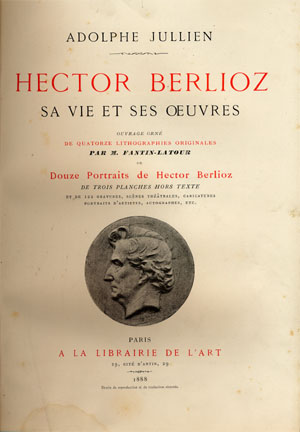

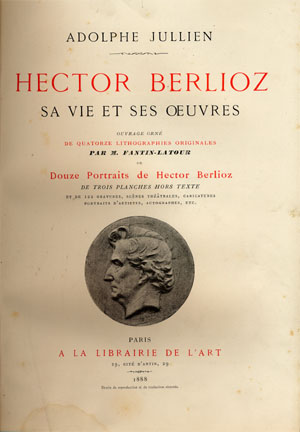

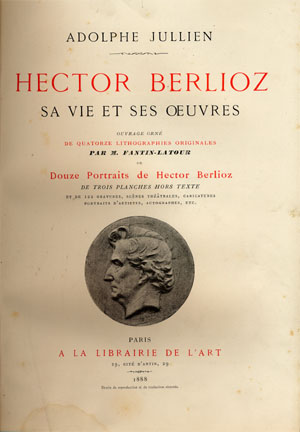

This shows the spine and title page of Jullien’s 1888 biography of Berlioz, reproduced from a copy in our collection. On the book itself see the discussion above.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir

Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997;

Page Berlioz: Pioneers and Champions created on 15 March 2012; this page created on 1 June 2020.

© (unless otherwise indicated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights reserved.