![]()

Introduction

The search for the Prix de Rome: 1826-1830

Election to the Institut: 1839-1856

Berlioz at the Institut: 1856-1869

Epilogue

Selected letters

Ilustrations

Chronology (separate page)

This page is also available in French

Abbreviations:

CG = Correspondance générale (1972-2003)

CM = Critique musicale (10 volumes, 1996-2020)

NL = Nouvelles

lettres de Berlioz, de sa famille, de ses contemporains (2016)

Bloom 1981 = Peter Bloom, ‘Berlioz à l’Institut

Revisited’, Acta Musicologica vol. LIII, fasc. 2, 1981, pp. 171-99

Tiersot 1911 = Julien

Tiersot, ‘Berlioz à l’Institut’, Le Ménestrel, August-September 1911

![]()

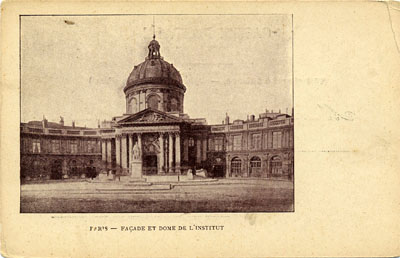

The Institut is something which is peculiar to France. Several countries have academies which may rival our own as regards the distinction of their members and the importance of their work. But France alone has an Institut where all the endeavours of the human mind are, as it were, bound together in a single whole, where the poet, the philosopher, the historian, the critic, the mathematician, the physicist, the astronomer, the natural historian, the economist, the lawyer, the sculptor, the painter and the musician can call each other colleagues.

Ernest Renan in 1867

In the sphere of intellectual and artistic endeavour, there existed one authority: the Institut. Berlioz was always attracted to it. This very attraction meant that at times he appeared inclined to combat it. But even when this was the case, his respect for the learned body was not thereby shaken. He may have been an opponent of academicians, but he was not opposed to the Academy. He never ceased to acknowledge what was superior in it. He could have adopted as his motto the saying of a later date: « If there is an Academy, I must belong to it », and in thinking this he was not doing it any injustice.

Founded in 1795, the Institut de France grouped together in Berlioz’s time no less than five Academies, all of which were even more ancient than the Institut itself: the Académie française (founded in 1635), the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres (founded in 1663), the Académie des sciences (founded in 1666), the Académie des sciences morales et politiques (founded in 1791, abolished in 1803, then reinstated in 1832), and the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which resulted itself from the fusion in 1816 of three Academies, those of painting and sculpture (founded in 1648), music (founded in 1669), and architecture (founded in 1671); these became the three sections of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Académie des Beaux-Arts, and the other two specifically musical institutions, the Académie royale de musique (the Opéra) and the Conservatoire de musique (the Conservatoire) were the three state institutions in France with which the whole career of Berlioz was closely associated, almost from the moment of his arrival in Paris in 1821 till his death in March 1869. Ambivalence was the keynote of his relations with these three bodies; an independent-minded outsider of genius, he found himself frequently in conflict with the French musical establishment and was viewed by it with suspicion.

Berlioz’s relations with the Institut divide naturally into 3 periods: first, the period from 1826 to 1830 when Berlioz as a student of music at the Conservatoire entered every year and eventually won the prestigious Prix de Rome competition for musical composition; second, the period from 1839 to 1856 when Berlioz sought to be elected to one of the seven places in the music section of the Académie des Beaux-Arts; and third, the period from his election to that position in June 1856 down to his death in March 1869, when he was now himself a member of the Academy (a separate page gives a chronological outline of the main dates and events). Berlioz’s relations with the Opéra and the Conservatoire are dealt with elsewhere on this site in separate pages. With these two specifically musical institutions, Berlioz was never able to achieve full acceptance: in the 1860s, in the final stages of Berlioz’s career, the Conservatoire gave only a limited number of performances of his works, and the Opéra failed to stage his greatest work, the opera les Troyens which had been conceived and written for it. But with the Académie des Beaux-Arts at least, Berlioz eventually became a full member and was able in his later years to enjoy the benefits as well as the obligations attached to his new status.

In his writings Berlioz has a great deal to say about the Institut and his relations with it, though there are significant differences in the evidence provided by different works. The Memoirs give detailed and colourful accounts of his successive attempts at obtaining the Prix de Rome in the period 1826 to 1830; the substance of these chapters goes back to articles written already in the 1830s (CM I pp. 99-112, 153-65), which were later reproduced in the series of excerpts published in the journal Le Monde Illustré in 1858-1859 under the title Mémoires d’un musicien. They also give a very extensive account of his subsequent trip to Italy in 1831-1832 as winner of the Prix de Rome (chapters 32-43). But they say nothing about his various attempts to become a member the Institut, and only include in the Postface a very brief retrospective summary of his election and time as academician. The gap is filled by the composer’s correspondence, by far the most detailed source of information for every stage of his relations with the Institut; the evidence of the letters has been extensively used here in a series of excerpts which span a period of more than 40 years from 1826 down to 1868 (all translations from the letters are by Michel Austin). Berlioz’s feuilletons in the Journal des Débats, the full text of which is available on this site, also have frequent occasion to mention the Institut in various contexts and will be referred to where appropriate.

![]()

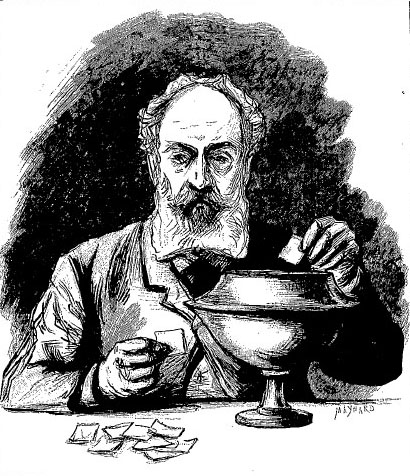

The Prix de Rome had a very long history: it was founded as far back as 1663, long before the Institut itself. Initially it was awarded only for painting and sculpture; the prize for musical composition was added much later, in 1803 (coincidentally, the year of Berlioz’s birth). Every year a first and a second prize were awarded for the composition of a cantata on a set libretto. Berlioz describes the rewards attached to the second and first prizes respectively (Memoirs, chapter 22):

This distinction (sc. the second prize) consists in crowns that are awarded in public to the winner, and a gold medal of little value; in addition it gives to the successful candidate free entry to all opera houses and plenty of opportunities of winning the first prize at the following competition.

The first prize has far more important privileges. It guarantees to the successful composer an annual pension of 3,000 francs for five years, on condition that he spends his first two years at the Académie de France in Rome [the Villa Medici], and the third travelling in Germany. He gets the rest of his pension in Paris, where he then does his best to get his music performed and avoid dying of hunger.

For Berlioz the Prix de Rome was a means to an end and not an end in itself: he needed official recognition to convince his sceptical parents who were opposed to his plans for a musical career. The material rewards of the prize mattered far more to him than any prestige attached to it. As early as 1827, at his first full attempt, Berlioz formed an unflattering view of the competition and how it was run (CG no. 76), and all his subsequent writings give the same negative presentation, starting with the letters written during the years when he was competing for the prize. The competition was marked by favouritism (CG nos. 76, 125), it was run by amiable but old-fashioned gentlemen terrified of novelty (CG nos. 125, 132, 133), the style of music expected from the candidates was pedestrian and unimaginative, and Berlioz had to restrain his own creative instincts if he was to win the prize (CG nos. 77, 132, 133, 160, 166). There was the further absurdity of the jury assessing the music from a piano reduction and not the original accompaniment for full orchestra (CG no. 77). The only incentive for competing was money (CG no. 95) and the need to impress his parents (CG nos. 127, 133). Winning the prize brought an additional and unwelcome twist: the enforced two-year stay in Rome and Italy, which made sense for students of the visual arts (for whom the prize was originally devised), but was an absurdity for musicians, given the pitiful level of music-making in contemporary Italy as compared with Paris or the German world.

The feuilletons Berlioz wrote in later years constantly return to the same ideas. He more than once refers ironically to his own experiences of the competition and the subsequent trip to Italy (Journal des Débats 15 August 1846; 14 July 1849; 19 October 1850; 10 June 1854). The style of competition cantatas was flat and conventional (23 June 1835; 14 December 1841; 31 May 1857). Prize-winners often turned out to be undistinguished composers, and if they showed merit, it was in spite of having won the prize and made the trip to Rome (29 June 1850; 2 December 1850; 29 May 1861). The absurdity of forcing musicians to spend two years in unmusical Italy is a theme Berlioz repeatedly returns to down to his very last feuilleton (3 October and 19 October 1841; 29 October 1844; 8 October 1863: ‘M. Bizet, a prize-winner at the Institut, has made the trip to Rome; he came back without having forgotten music’).

The posthumous Memoirs present the same view in the chapters which relate Berlioz’s successive attempts from 1826 to 1830 to win the prize (see esp. chapters 14, 22-23, 25, 29 and 30). The presentation is deliberately satirical and the competition is presented as a farce. Berlioz characteristically gives prominence in chapter 23 to the revelations of the porter of the Institut, an old man of the name of Pingard. Pingard gives Berlioz the inside story of how the competition is actually run and the prizes awarded, with elaborate horse-trading between the different members of the jury over their favourite students, and Pingard is the first to tell Berlioz off-the-record that he had won the second prize (in 1828).

In the Memoirs Berlioz relates briefly his very first attempt at the competition (ch. 10):

[…] I entered the competition for musical composition which takes place every year at the Institut. Before being admitted to the competition the candidates have to undergo a preliminary test [by writing a fugue], after which the weakest are eliminated. I had the misfortune of being among these. My father got wind of this and this time had no hesitation in warning me that I should no longer count on him if I persisted in staying in Paris, and that he was withdrawing my pension.

No specific date is mentioned by Berlioz for his first attempt to compete, except that he places it after the performance of the Messe solennelle, which took place on 10 July 1825 at Saint-Roch in Paris. It must belong to the following year 1826. A letter of Berlioz to his friend Édouard Rocher dated 15 July 1826 (CG no. 61) mentions that the competition had already started then, but strikingly it does not specify whether Berlioz had taken part in it. Presumably he did, and the likelihood is that in this letter Berlioz kept quiet about his failure, though word of it evidently reached his parents (the fugue he wrote on this occasion is extant, as is that for the competition of 1829: see NBE vol. 6). The next letter, about two months later and to the same correspondent (CG no. 63), implies that by this time Berlioz was actively looking forward to the competition of the following year, though in the event he took much longer to win the prize than he anticipated (cf. on this CG no. 79).

The following year (1827) Berlioz passed the preliminary test successfully and entered the competition on 28 July (CG no. 76). The subject of the cantata was La Mort d’Orphée and Berlioz felt he had a good chance to win at least a second prize. But his work was ruled out of court on the grounds that it was ‘unperformable’: the pianist entrusted with the piano reduction of the full score was simply out of his depth (Memoirs ch. 14; cf. CG no. 77). In a concert on 26 May the following year he attempted to get the cantata performed in public, though that attempt fell through (Memoirs ch. 19). Later in that year (1828) Berlioz had more success with the cantata Herminie, and this time he obtained the second prize (Memoirs ch. 22; CG no. 95). According to all precedents Berlioz could have expected to win the first prize the year after (1829) and letters written earlier in that year, before he entered the competition, show his optimism (CG nos. 125, 127). This proved to be a miscalculation. The subject of the cantata was Cléopâtre, and it so fired his imagination that he threw caution to the winds and wrote a work of daring originality. The musicians of the Academy were so disconcerted that they could think of no other way of saving face than not to award any prize that year (Memoirs ch. 25; CG nos. 132, 133).

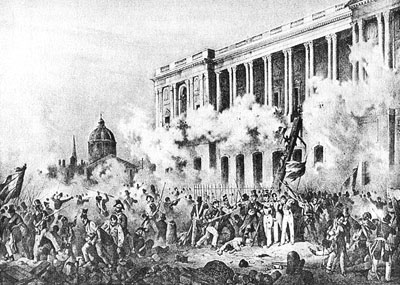

For Berlioz this was a serious setback; it had at least the advantage of almost guaranteeing his success the following year (1830), when two first prizes were now on offer, but only if he was careful to write a safe work that could not cause any offence. There was now also a new incentive of a personal kind: during the spring Berlioz had fallen in love with the young and talented pianist Camille Moke, and success at the competition was a precondition for Camille’s parents to consent to Berlioz’s engagement to their daughter (CG nos. 160, 166, 168). The competition took place in extraordinary circumstances: on 27 July, while Berlioz was locked up in the Institut writing his cantata Sardanapale (CG no. 169), the people of Paris rose up against the monarchy of Charles X and the Institut came under cannon fire; Berlioz emerged from the Institut on the 29th, the last day of the revolution, and promptly joined the insurgents in the streets of Paris (CG no. 170). Calm was restored; Berlioz was now confident of having won the prize (CG no. 171), though confirmation only came with the official decision on 21 August (CG no. 172). After several postponements (CG nos. 173, 176, 183), the prize-giving ceremony took place on 30 October (CG no. 188). It was a double disappointment for Berlioz, musical and personal. Once sure of the prize he had added a spectacular finale to the cantata; it made a great impression at the rehearsal but misfired completely at the public performance through an error on the part of the players. And Berlioz was alone at the public ceremony: Camille Moke and her mother failed to attend after all despite earlier promises (CG nos. 173, 183). The Memoirs give a detailed account of the whole competition and the prize-giving ceremony which is in line with the account in the letters at the time (chs. 29-30).

Alone of the four cantatas Berlioz wrote for the Prix de Rome competition, the complete score of Sardanapale has not been preserved and exists at present only in a fragment, though a copy of the work may conceivably lurk somewhere in the vaults of the Institut (the scores of all the cantatas are to be found in NBE vol. 6). Berlioz never intended to publish any of his Rome cantatas, but he made extensive use of music from them in later works (see Berlioz and his music: self-borrowings).

Winning the prize committed Berlioz to go and spend the next two years in Italy; for personal as well as musical reasons he tried to secure exemption from the rule, but despite influential support he was unsuccessful and had to depart at the end of the year, uncertain of the future and about Camille Moke’s true feelings and intentions. The story of his trip to Italy and experiences there is covered in detail elsewhere on this site.

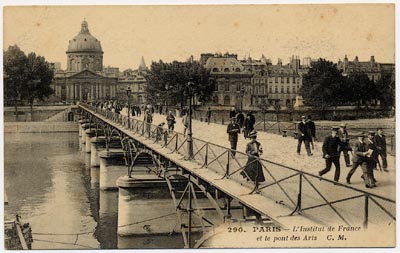

![]()

The total membership of the three sections of the Académie des Beaux-Arts was fixed in 1816 at 50 in all; the music section, the one which concerned Berlioz, was the smallest and in Berlioz’s time numbered only 7 members. The members of the different sections, known as the ‘immortals’, remained in post until their death, at which point the vacancy was filled by the election of a new ‘immortal’. Membership of the Institut carried special status, in itself and because of its permanence: it was a privilege in French society to be able to advertise the title ‘Membre de l’Institut’. Membership of the Institut carried with it duties and responsibilities, such as attending the sectional meetings, which in Berlioz’s time normally took place every Saturday throughout the year, one annual session of the whole Académie des Beaux-Arts which was open to the public (normally in October; cf. CG no. 2768), and sessions every 3 months of all five Academies of the complete Institut.

Berlioz evidently regarded membership of the Institut as a privilege worth acquiring, and considered applying from the very first opportunity that presented itself (in 1839; see below). But from his letters it is clear that the honorific aspect, though important, was not decisive by itself: he regarded a number of Academicians as nonentities who did not deserve their place, and stated quite frankly that for him a major attraction of the position was that it guaranteed a regular annual income for life (NL no. 773bis, CG nos. 1783, 2145, 2156bis). The sums involved were relatively modest (membership carried a lifelong pension of around 1,500 francs, paid monthly subject to attendance — see below); but it should be remembered that Berlioz had no regular income apart from his salary as librarian of the Conservatoire (from 1839 onwards; cf. CG no. 608 and the letter of Félix Marmion to his niece Nancy Pal of 17 January 1839), and for 30 years of his life he had to earn his living by writing feuilletons, an obligation that he found time-consuming and often irksome (see the collection of material on this subject on this site).

Since membership of the Institut was for life, vacancies, particularly in the small music section, were both rare and unpredictable (unlike the annual Prix de Rome competition for musical composition). They could therefore happen at inconvenient times. In 1844 Henri Berton died (22 April); he had been an opponent of Berlioz in the days of his attempts to win the Prix de Rome (cf. CG nos. 77, 125, 172). Adolphe Adam was appointed as his successor the following June. There is apparently no evidence that Berlioz even considered applying for the vacancy: at the time, as well as serious problems in his domestic life, he was very busy with preparations for a large festival which eventually took place on 1st August. In 1853 Georges Onslow died (3 October); Berlioz did apply, but at the time he was travelling in Germany giving a series of concerts, and the application he put in from a distance was both perfunctory and late (CG nos. 1644, 1645, 1653).

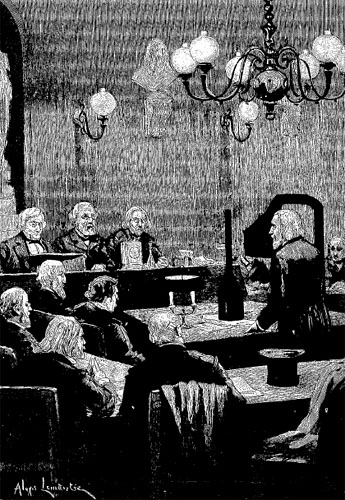

The electorate for the appointment of new members consisted simply of the 50 members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts; in practice not every member actually took part in the vote, as shown by the figures for elections which involved Berlioz as a candidate. In 1851 Ambroise Thomas received 30 votes, Niedermeyer 5 and Barton 3, making a total of 38 votes cast (Berlioz did not receive a single vote; CG IV p. 30 n. 1). In 1856 when Berlioz was elected he received 19 votes, Niedermeyer 6, Gounod 6, Félicien David 4, and Panseron 2, making a total of 37 votes cast (CG V p. 321 n. 1). Since the electorate was very small, it was essential for candidates to canvas in person for the support of individuals, a time-consuming obligation that Berlioz (and no doubt other candidates) found irksome but unavoidable (numerous references to this: CG no. 649, NL no. 773bis, CG nos. 1388, 2132, 2139, 2145). In 1854 Berlioz had to abandon a projected visit to Munich in order to be able to concentrate on his application (which in the end was unsuccessful: CG nos. 1783, 1784, 1785). Though in principle every member of the electorate had an equal vote, in practice the attitude of the members of the relevant section, in Berlioz’s case the music section, was influential with the other sections. Berlioz believed that one reason why he took so long to be elected was because of the enemies he had made through his writings as music critic: he could have become a member of the Institut eight or ten years earlier (CG no. 2125, in 1856). As late as 1851 the entire music section was hostile to him, and he did not obtain a single vote (CG nos. 1382, 1388, 1392). In 1856, by contrast, the music section was now well disposed, with the exception of Carafa (CG nos. 2132, 2139, 2141, 2145, 2155).

Vacancies for which Berlioz applied or considered applying occurred in 1839, 1842, 1851, 1853, 1854 and 1856, when he was eventually successful. The evidence for these comes not from the Memoirs, which are completely silent on his attempts before 1856, but from the composer’s correspondence, and from the official archives of the Institut which, among other documents, have preserved the formal letters of application that candidates had to submit. There is no need to go through each episode in detail, though 1839 calls for a word of comment. On 3 May of that year Ferdinand Paër died; a letter of Berlioz to his father dated 11 May mentions the event and states explicitly that he intended to apply for the vacancy at the Institut, even though he knew he had no chances of being elected, and expected either Onslow or Adam to succeed; he also refers to the chore of having to make a series of visits [sc. to solicit the votes of other academicians] (CG no. 649). Two entries in the Paris paper la Revue musicale, dated 9 May and 23 May, refer to this. On 9 May: ‘The death of M. Paër leaves a vacancy at the Institut. The candidates who are applying to fill it are MM. Adam, Berlioz and Onslow’. Then on 23 May: ‘There are only 4 candidates left for the vacancy at the Institut caused by the death of Paër. M. Berlioz, on learning that Spontini was lodging an application, felt he had to withdraw’ (cited by Julien Tiersot, Le Ménestrel 26 August 1911, p. 269). This evidence seems conclusive, but it is not mentioned by Peter Bloom 1981, pp. 174-5 (also NL p. 172 n. 1) who emphasizes — correctly — that Berlioz did not submit a formal application, since none is preserved in the archives of the Institut, and challenges the standard view of Tiersot and others that Berlioz did apply but then withdrew on hearing of Spontini’s application. The standard view still seems to us to be correct.

The first formal letter of application by Berlioz dates from 1842, and is the first of five; they are too long to quote in full but show interesting variations (for excerpts see CG nos. 786, 1389, 1645, 1781 and 2133). The applications of 1842 and 1854, as well as listing his musical works to date, also mention his work as a writer and music critic. The application of 1853 is astonishingly perfunctory and does not even list his musical works. The application of 1856, which was successful, is the most polished; Berlioz took great trouble in preparing the ground, as letters of 1856 show. In his application he concentrates exclusively on his musical works which he lists in sequence with their opus numbers, and makes special mention of l’Enfance du Christ, first performed on 10 December 1854 in Salle Herz in Paris: the work proved an instant success and was soon performed several times in Paris and abroad, and enhanced his reputation as composer in France. It is likely that it contributed significantly to the success of his application in 1856, though it should be noted that it took 4 rounds of voting before Berlioz could achieve an absolute majority over 4 other competitors. Tiersot observes that this was in practice probably Berlioz’s last chance to be elected: the next vacancy only occurred in 1866 with the death of Clapisson (CG nos. 3112, 3132), by which time it might have been too late.

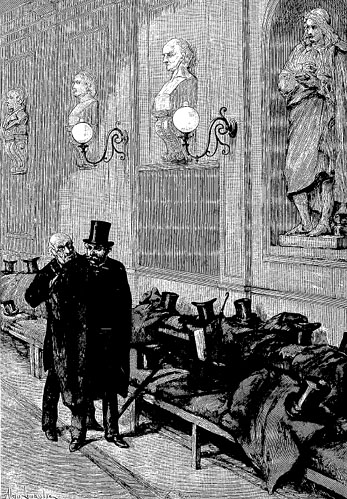

![]()

To my great surprise, I was made a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts of the Institut. I speak there from time to time, and though the remarks I make about our academic habits are rather useless and do not produce any results, the relations I have with my colleagues are entirely friendly and extremely pleasant.

Thus Berlioz in the Postface of his Memoirs, summarising in one short and rather dismissive paragraph well over a decade of his life as an active member of the Institut following his election on 21 June 1856. The only other mention of the Institut in the last two sections of the Memoirs is an anecdote later in the Postface: when asked by the Grand-Duke of Weimar about the nocturnal duet of the women at the end of Act I of Béatrice and Bénédict, Berlioz told him that he had sketched it one day at the Institut while a colleague was making a speech…

The Memoirs leave here a great deal unsaid. They do not mention the repeated attempts made by Berlioz over the years to be elected to the Institut (see the previous section). And despite what Berlioz implies, his election in 1856 was not entirely unexpected. Since at least 1854 he had set his heart on securing admission to the learned body come what may (CG nos. 1784, 1785), and when the vacancy occurred in 1856 his correspondence shows that he went to great lengths to prepare the ground for his application (CG nos. 2124, 2125, 2132, 2134, 2138, 2139). The letters also show how pleased he was at his election, and especially how gratified he was by the joy it caused to his friends (CG nos. 2141, 2143, 2144, 2145, 2146, 2149, 2156bis). Significantly, whereas in general only a small proportion of the numerous letters adressed to Berlioz have survived (on this point see the remarks elsewhere on this site), a large number of the letters of congratulation he received on this occasion were preserved by him and are extant (CG no. 2140; see also CG nos. 2142, 2147, 2151 and CG V p. 322 n. 1; CG [VIII] nos. 2141bis, 2148bis, 2148 ter; NL pp. 445-60). Many of these letters are now at the Hector Berlioz Museum in La Côte Saint-André, such as the letter of 23 June from his sister Adèle. The title ‘Membre de l’Institut de France’ evidently meant more to him than he admitted: he put it on the title-page of his Memoirs, but also on his visiting card, as emerges from a letter: the title could unlock doors (CG no. 2334). He occasionally used the title after his signature in letters of an official kind (CG nos. 2223, 2285, 2382, 2572, 2875 and the letter of 21 May 1865 published on this site).

To the bare summary of the Memoirs Berlioz’s correspondence down to 1868 adds some circumstantial detail and provides a more rounded view of what it meant to be an academician; there is also the evidence from the archives of the Institut itself (for which see Bloom 1981, pp. 183-99).

As a result of his election Berlioz’s timetable changed abruptly: he was now saddled with the obligations of his new status. On 28 June he was introduced to his new colleagues and soon after started judging the annual competition for the Rome prize (CG no. 2149). From the time of his election to the end of the year he attended no less than 16 meetings at the Institut in all, as indicated by the attendance lists which are preserved among the archives at the Institut, and henceforward this was to be a normal pattern (see Table I in Bloom 1981, p. 198). The attendance lists show that in general Berlioz was assiduous in signing on for the regular sessions at the Institut, which took place every Saturday throughout the year. Comparison of the attendance lists with the dates of his major trips abroad reveals an interesting fact: as a general rule Berlioz did not allow his travels abroad to interfere more than necessary with his presence at the Institut, and made a point of signing the attendance list regularly before his departure and then again soon after his return.

For example, he missed all or most sessions during the month of August between 1856 and 1861, when he was away in Baden-Baden organising and conducting a major concert; he nevertheless signed on for 3 sessions in August 1862 and 4 in August 1863, despite having travelled to Baden-Baden for performances of Béatrice et Bénédict. In April 1863 he spent much of the month on a visit to Weimar and then to Löwenberg, but he attended the Institut on 28 March just before his departure and on 28 April after his return. In December 1866 he was away from Paris from the 5th to the 21st to conduct a performance of the Damnation of Faust in Vienna, but he attended the Institut on 1st December before his departure and again on 22 December immediately after his return. In February 1867 he departed from Paris on the 22nd for a visit to Cologne and was back at the end of the month; he signed in at the Institut on 16 February before leaving and again on 3 April after his return.

Visits to the Institut are mentioned in the composer’s correspondence quite frequently and imply that for him it was a regular activity (CG nos. 2150, 2256, 2267, 2315, 2480, 2502, 2564, 2630, 2724, 2768, 3030, 3073, 3110, 3149, 3241, 3279). Two letters hint at one reason why he was assiduous in his visits: if he did not sign on for attendance he would lose his ‘token’ (jeton) and would suffer financial loss as a result (CG nos. 3240, 3274). How the system worked in practice is explained by a passage from a book on the Institut of 1896 which is reproduced below in translation: originally, in the 17th century, tokens with monetary value were distributed to members at the sessions they attended; this was later replaced by attendance lists, on the basis of which members were paid in cash at the Institut every month, the amount depending on their attendance record. It will be noted that in CG no. 3240 Berlioz seems to imply that by going to sign on at the Institut he received an actual physical token (jeton); these were in fact commonly used in many institutions in France at the time and were known as jetons de présence [cf. CG no. 3239], though it is not clear whether they were still used at the Institut. It may also be that by this time the word jeton was only used figuratively as being the equivalent of signing the attendance list. Be that as it may, this evidence helps to understand Berlioz’s regularity in attending meetings. Rightly or wrongly Berlioz was worried about his budget, and money matters figure frequently in his letters, increasingly in his later years after he had given up writing feuilletons (CG nos. 2839, 3092).

With his election in June 1856 Berlioz moved from being an outsider and frequent critic of the Institut to being a full member. This involved a series of obligations. He was now part of the jury that judged entries for the Prix de Rome (CG nos. 2149, 2502, 2564, 2870, 3244; see Bloom 1981, Table 2 p. 199). After the reorganisation of the competition in November 1863 (Memoirs ch. 22 note 1), he continued to serve as member on the jury (CG nos. 2870, 3239, 3244). He was involved in the election of new members to the Institut (CG nos. 2195, 3030, 3112, 3149). In 1859 he supported Liszt’s application to become foreign member of the Institut, though he was not successful (CG nos. 2428, 2429, 2442, 2443, 2447, 2449, 2678). He was called upon to participate in various commissions and juries, which could be time-consuming and onerous (CG no. 2315, 3239). In 1862, on the death of Halévy, Berlioz was pressed against his better judgement to apply for the post of permanent secretary of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, though to his relief he was not appointed (CG nos. 2601, 2608). On a lighter note Berlioz sent to the Académie in two instalments an irreverent letter relating his visit to Baden-Baden in August 1861. It was supposed to be read out at the annual public session of the Académie, but when they were published in the Journal des Débats on 11 September and 12 September 1861 a note was added: ‘The letter seemed written in a style too far removed from academic habits and was not read out in the public session’ (the letter was later reproduced in À Travers chants). Though Berlioz was now a member of the musical establishment, there was no risk of his ‘going native’ (cf. CG no. 2153).

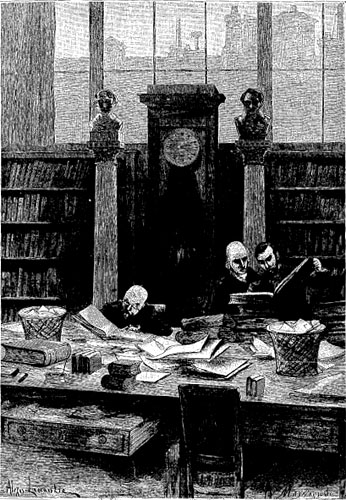

Membership of the Institut had its compensations. One attraction of the Institut was its library: throughout his life Berlioz was an avid reader. Ernest Legouvé, a friend of Berlioz, related in his Soixante ans de souvenirs of 1886 (chapter 16, section 9) that according to the librarian of the Institut, Berlioz usually arrived early on Saturdays before the meetings to read Virgil in the library. A letter of 1866 corroborates this: it shows him spending time in the library reading biographical works before the official sessions (CG no. 3147). Berlioz also used the library for writing: some letters were probably written there (CG nos. 2150, 3030) and a letter of 1860 indicates that the review he published of Wagner’s concerts in the Journal des Débats (9 February 1860, reproduced in À Travers chants) was partly drafted there (CG no. 2477).

There was also the personal side to the Institut: in his own and in the other academies, Berlioz had congenial friends and acquaintances, some of them of long standing, as for example the painter Horace Vernet, the architect Pierre Duc, and the writer Ernest Legouvé, all of whom he met during his stay in Italy in 1831-1832. In 1858 Berlioz organised a reading of the poem of les Troyens at the home of Jacques Ignace Hittorff, an architect and friend at the Institut, before a gathering of painters, sculptors and other architects from the Institut, and the occasion was a success (CG nos. 2274, 2279). In the autumn of 1866 a revival of Gluck’s Alceste at the Opéra, carried out under Berlioz’s supervision, attracted appreciative listeners from painters and sculptors from the Institut ‘who have a feeling for antiquity’ (CG no. 3180). In general membership of the Institut brought with it a more active social life for both Berlioz and Marie — and additional expenses (CG no. 2348).

Membership of the Institut also brought with it a series of formal social obligations: the academies were institutions of state. Hence when on 14 January 1858 an attempt was made on the life of the emperor and empress as they attended a performance at the Opéra, Berlioz went with many others to the Tuileries palace to sign a declaration of support; he then helped in drafting a collective address to the emperor on behalf of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which was then amplified into an address by all the academies together (CG no. 2272).

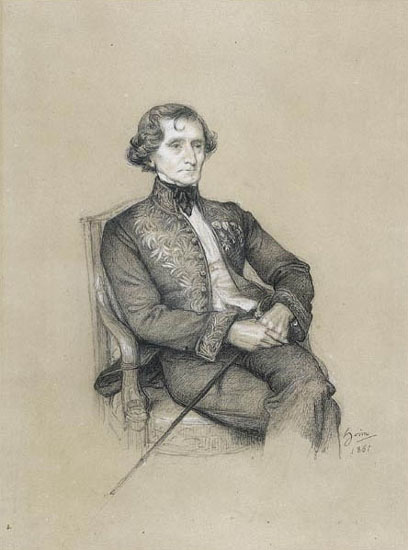

Members were expected to participate in official occasions, at which they were required to wear the official uniform of their status, complete with ceremonial sword, something which Berlioz disliked but could not avoid (CG nos. 2214, 2961, 2970, 3074; see below a portrait of Berlioz in formal academic dress). Receptions and balls were frequently given by the Emperor at the Tuileries palace; Berlioz and Marie attended many of them over the years, though evidently Marie enjoyed them more than Berlioz did (CG nos. 2214, 2689, 2850). But Berlioz did try to turn the ease of access to the court which he now enjoyed to good use: he sought to interest the emperor and empress in his opera les Troyens, which he was busy composing at the time of his election in 1856 (CG no. 2145). Over the next two years he made a series of attempts to read the poem of les Troyens to the emperor or the empress (CG nos. 2219, 2222, 2235, 2256, 2275, 2277, 2279, 2292, 2293, 2299, 2334). The Memoirs (Postface) reproduce a letter dated 28 March 1858 which Berlioz intended to send to the emperor asking for his support in getting les Troyens performed. The letter, which Berlioz signed ‘Membre de l’Institut’, was never sent: the emperor, he was told, would have found it ‘inappropriate’. The Memoirs go on to relate the fruitless attempts Berlioz made to get the emperor at least to read the poem of the opera: but Napoleon III was not interested in music (CG no. 2334), unlike some of the German kings and princes that Berlioz had met (cf. CG no. 2857), and in the end Berlioz had to settle for a truncated performance of his opera at the smaller Théâtre Lyrique.

On 12 November 1867 Berlioz left Paris for his last trip to Russia, and only returned to Paris on 17 February of the following year. He signed the attendance list at the Institut on 9 November not long before his departure, and again on 22 and 29 February 1868 after his return and despite his fatigue. After he had recovered from the accidents he had suffered during his visit to Monaco and Nice in March, he resumed his regular visits to the Institut, as he mentions in a letter of 14 June to Estelle Fornier, though he no longer had the strength to attend the sessions (CG no. 3363). Ernest Legouvé tells the story of Berlioz making a special trip to the Institut to cast his vote for Charles Blanc, in return for a service he had received from him twenty years earlier (Soixante ans de souvenirs, chapter 16 section 6). Legouvé melodramatically places the story ‘a fortnight’ before Berlioz’s death; the vote took place in fact on 25 November 1868 (Tiersot 1911; CG VII p. 716 n. 1). As long as he was able to Berlioz attended the Institut: he signed in twice in December, and for the last time on 6 January 1869.

![]()

Berlioz died on 8 March 1869. Members of the Institut participated at the funeral ceremony on 11 March at the church of Sainte-Trinité and then at Montmartre cemetery, as reported in the weekly journal Le Ménestrel of 14 March 1869: the Institut always honoured its deceased members (cf. CG no. 3112). The participants from the Institut included MM. Guillaume, president of Académie des Beaux-Arts, Camille Doucet of the Académie française, Baron Taylor (an old friend of Berlioz), the composers Ambroise Thomas and Charles Gounod from the music section, and a deputation from the Institut which included in addition MM. Dumont, Pils, and Beulé (the permanent secretary who had been appointed in 1862). At the cemetery Guillaume made a speech on behalf of the Institut, which is reproduced at the end of the report in Le Ménestrel. Numerous obituary notices were published at the time, including one by Berlioz’s friend Ernest Reyer in the Journal des Débats (31 March 1869); following perhaps the example of Berlioz who declined to stand against Spontini in 1839, Reyer did not present himself to be Berlioz’s successor at the Institut, and the vacancy was filled by Félicien David (Reyer himself was later elected to the Institut and inherited from Berlioz his academician’s dress).

When Berlioz died his music had not achieved its proper recognition in his native country; yet within a decade of his death it was to experience a remarkable revival in Paris. This is traced in detail in a separate page on this site. One manifestation of the revival was the launching of a subscription in 1884 for the building of a monument in honour of Berlioz at Square Vintimille (later renamed Square Berlioz); Viscount Delaborde, the permanent secretary of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was president of the committee which organised the project, and it was supported by the entire music section of the Institut. The monument was eventually inaugurated on 17 October 1886 and the ceremony received advance publicity in the Paris press. It was reported in several newspapers: L’Illustration and La France Illustrée (both on 23 October), Le Journal Illustré (31 October), and most fully in L’Univers Illustré on 23 October. The Institut participated fully in the ceremony: speeches were made by Viscount Delaborde, Charles Garnier, and especially by Ernest Reyer, whose speech is reproduced in full (in French) in the last mentioned article.

![]()

To Édouard Rocher (CG no. 61; 15 July)

[…] (Berlioz is composing a 3 act opera) M. Lesueur is extremely pleased with the first two acts, and I will do my best with the third. He is adamant that I should enter the Competition of the Institut next year, and to this end he wants me to follow a class in counterpoint and fugue at the Conservatoire. I went to see Cherubini on the subject, and as I wanted to show him something I had written so that he should know what I am capable of, he replied: « No, no, this is not necessary, I know you; just bring me an excerpt from your birth certificate ».

Up till now I was only entered in the Conservatoire’s register as a private pupil of Lesueur. That is why Cherubini himself, after the performance of my Mass, asked Lesueur to send me to him. You can see there once more the self-esteem of masters who, as soon as they spot some talent in a pupil, want to catch him for themselves. When it can be said that I have taken lessons in counterpoint at the Conservatoire, Cherubini will back me with all his influence. Otherwise no!

Because of all this (as Cherubini asked me the other day why I was not bringing him an excerpt from my birth certificate) could you please send it to me. But I do not want anyone to know about it, because of the wild fantasies my parents might conceive as a result. Ask Jardinet for it secretly or in an adroit way, and send it to me as soon as possible. Consult Marc on the matter, but do not talk to anyone else about it.

This year’s competition is already open. Pâris is expected to get the prize […]

To Édouard Rocher (CG no. 63; ca. 10 September)

[…] (Plans for a trip to Brazil, but Berlioz does not want to leave Paris) First, I would have had to give up the Prix de Rome for which I am at the moment the leading candidate, now that Pâris and Simon will be out of the way. At least M. Lesueur is designating me as due to get the first prize in at least two years, if justice prevails. My competitors are all fools, except for a second prize of this year, who will always get the first in preference to anyone else, thanks to the praiseworthy custom of what they call the Institut’s Competition. […]

![]()

To his sister Nancy Berlioz (CG no. 76; 28 July)

[…] I am entering the Institut in an hour and a half.

The preliminary competition took place the day before yesterday, to determine which candidates were to be admitted to the full competition. We were set the task of writing a fugue in strict style, a kind of musical test of very limited value and very difficult to solve. There were only four of us, and out of this number I am the only one who correctly wrote what they call the answer and which is the main object of the fugue. Another one who had already won a second prize last year and to whom the first is assigned this year, had for this reason also got the answer wrong, but had somehow compensated for this shortcoming through another kind of quality which he had spread throughout his work; he could have passed at a pinch, but as of right there should only have been two of us though in practice we are four. The other two, who are pupils of Berton, were admitted despite the very strenuous opposition of MM. Cherubini and Lesueur.

You have there already an illustration of how judgements are made at the Institut. I am resigned to this; they say that I will get the second prize, and if so I will take it, but there will be little glory for me in defeating my two opponents; they simply have very little idea of what dramatic music is. […]

P. S. Every evening we will have a reception in the great courtyard of the Institut, friends and acquaintances are allowed to visit us from six to nine o’clock. There is an invigilator who makes sure that nothing is brought to us from outside which might be related to the subject of the competition.

[See also the letters of Nancy Berlioz to her grandfather Nicolas Marmion of 2 August and of Mme Berlioz to Nancy of 1 or 8 September]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 77 [see vol. VIII]; 29 November)

[…] I had sent letters of invitation to all the members of the Institut, as I was keen that they should hear an actual performance of what they call unperformable music. The fact is that my Mass is thirty times more difficult than my competition cantata, and you know that I was obliged to withdraw because M. Rifaut was unable to perform me on the piano, and that M. Berton lost no time in declaring me unperformable, even by an orchestra.

My great crime, in the eyes of that cold and frigid classical composer (for the time being at least), is that I am trying to do something novel. […]

Must I sink so low as to compete a second time?… But I have to, my father wants this; he attaches very great importance to this prize. Because of him, I will enter the competition again; I will write them music for a little bourgeois orchestra with two or three parts, which will have as much effect on the piano as the most lavishly scored orchestra; I will be generous with redundant phrases, since those are the forms that great masters have submitted to, and that one must not seek to do better than the great masters, and if I obtain the prize, I swear that I will tear up my scene before the eyes of these gentlemen, as soon as the prize is awarded.

I am telling you all this with passion, dear friend; but you cannot imagine how little importance I attach to it; I am consumed with a grief which nothing can dispel […]

![]()

To his sister Nancy Berlioz (CG no. 79; 10 January)

[…] As I was not destined to be a creative artist, my parents were opposed to my following this career, and they only yielded to my persistence; as I had not been encouraged from an early date in this direction, I was not in a position to acquire a talent as performer which would enable me to earn money until such time as my works would do so; all the young composers I know have on the other hand this advantage; and the prolonged opposition I had to put up with has set me back at least three years; I would have had this miserable prize of the Institut two years ago, if I had been able to prepare for it earlier. […]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 95 [see vol. VIII]; 15 July)

[…] I am unable to copy parts myself, since for the last two weeks I have been locked up at the Institut; this abominable competition is of the utmost necessity for me, as it brings money and that nothing can be done without this base metal.

Auri sacra fames, quid non mortalia pectora cogis! [Accursed lust for gold, to what extremities you reduce human hearts!]

My father was not even prepared to provide for the expense of my stay at the Institut; it was M. Lesueur who stepped in. […]

![]()

To his mother Joséphine Berlioz (CG no. 125; 10 May)

[…] The time of the Institut’s competition is approaching, it will be in July. I am going to beg M. Champollion to see Cherubini, whom he knows particularly well, and to try to find out whether he still bears me a grudge and intends to maintain his opposition to me this year. I have another supporter in the music section, namely Auber, who has just been appointed member of the Institut to replace Gossec. I am on excellent terms with him, though I have a strong aversion for the kind of music he writes, he is very well disposed, and I know that he has an extremely favourable opinion of me.

I would very much like to be rid of this pitiful farce; Berton is one of those I am most afraid of, this old driveller cannot forgive me for being passionately devoted to the music of Spontini, who according to him is after all not without talent. The author of La Vestale is not without talent!... Oh really, if there were a few of his calibre, the Institut would be nothing but a lunatic asylum. […]

To Édouard Rocher (CG no. 127; 14 June)

[…] I am obliged to maintain a façade with my parents which is quite different from what I really am, so please do not let anything transpire. But I wish I had the strength to compete at the Institut in a month’s time. All the odds are in my favour, and because of my parents I covet this prize. Everyone believes that I will get it, especially now that my work on Faust which I have just published is causing a tremendous stir in the musical world. […]

To his father Louis Berlioz (CG no. 132; 2 August)

I waited for everything to be over to reply to mother’s latest letter, which I received at the Institut together with the note it contained. The verdict was announced yesterday and there is no first prize, neither for myself nor for anyone else. The Institut declared that there was no case for awarding it now and reserved it for next year, with the option of awarding two first prizes if it thought fit. M. Lesueur was ill and was unable to take part in the proceedings, and that is what did me so much harm. All the same Cherubini and Auber have supported me; Messrs Pradier and Ingres, great admirers of the German School, made a long speech at the end of the session in which they gave vent to their indignation; they said it was inconceivable that such a body should pronounce so lightly on me, whose record was known and whose work could not be understood from such a performance.

The fact is that Mme Dabadie, who was due to sing for me, was forced to break her promise because of the dress rehearsal for William Tell, which was scheduled at the same time as the Institut’s competition. She sent me her sister, a student at the Conservatoire, who is totally inexperienced and had had only a few hours to get ready.

But the main reason for all this is that, since the verdict of public opinion was that the prize was destined for me, I felt I had sufficiently strong support to allow myself to write as I feel, instead of holding back as last year. The subject was the death of Cleopatra; it inspired in me many things which seemed to me grand and novel, and I composed without hesitation, which is where I was at fault. All these gentlemen were well disposed towards me, but they were completely out of their depth, and for the musicians my work was as it were a satire of their style, and this wounded terribly their self-esteem.

I have just met Boïeldieu on the boulevard. He came straight to me and spent an hour in conversation. Here is the gist of what he said. « My friend, what have you done? We intended to give you the prize, we believed that you would be better-behaved than last year, but on the contrary you have gone a hundred times further in the opposite direction. I can only pronounce on what I understand; so I am far from saying that your work is not good, and there are so many things that I have heard that I have only got to understand and admire through repeated hearings! But you see, I have not yet been able to understand half of the works of Beethoven, and you are going further than Beethoven. You have a volcanic temperament which is far above anything we are able to experience; besides, I could not help saying yesterday to these gentlemen: With the kind of ideas he has, this young man must despise us from the bottom of his heart, he refuses absolutely to write a single note like everyone else. He must even have novel rhythms, and would like to invent modulations if such a thing were possible. Everything we do must appear to him commonplace and old-fashioned! »

For Catel and Boïeldieu that is the key to the riddle. Auber and Cherubini nevertheless sided with me for personal reasons, but their reaction to my work was the same, though much less so in the case of Cherubini than the others.

As for the non-musicians among the members of the Institut, they could not make any sense of it; it is as though you asked Prosper [Berlioz’s younger brother, then aged 9] to read Faust. As for the other winner of the second prize who was competing with me for the first, he got nothing for the opposite reason; he was too flat and aroused ridicule. […]

To his sister Nancy Berlioz (CG no. 133; 12 August) [cf. also CG no. 134]

What can I say to you, my poor sister, as you say this damned competition only interested me for my father’s sake. For him it is at least a consolation of sorts that no first prize was awarded and that no one was placed above me. I had it in my grasp, said Boïeldieu, they had all come with the intention of giving me the prize, but they absolutely refuse to encourage me in this direction. I had a long conversation with Boïeldieu, where among other naïve things he confessed that these gentlemen shared his way of thinking, namely that « with the ideas he has and the kind of music he writes, thisyoung man must feel utter contempt for them. Since you detest commonplaces so much, he told me, you must find me abominably flat. But one cannot innovate all the time, and that is what you are trying to do. I bet that you must be an admirer of Gœthe and Shakespeare!… Besides, you have a volcanic temperament, you want to go further than Beethoven, and I cannot understand half of Beethoven, so how do you expect me to understand you, I who have not studied harmony in any great depth and only like music that soothes me. Your outbursts terrify me, I try to discover the reason for your effects but am unable to; I am not saying that your work is bad, far from it, but I need more time to understand it, and especially it calls for an orchestra instead of a piano ».

In response to all these fine words I remained like a stone or like the Statue at the Stone feast.

What can one say in answer to these kind of confessions? He does show special regard for me, mingled with a kind of amazement; he made me promise to go and visit him at home, so that he could study me better. I have been there already once, also to Auber’s; they are in cahoots and say the same things to me, which only serves to convince me that in order to get the prize I must do what I did last year, that is clip my wings and in no way yield to my inspiration; that is the mistake I made this time round. A musician from the Opéra gave me an excellent piece of advice before I entered the competition, which I should have followed. « You ought to get yourself bled in all four limbs, he said, settle for a diet of whey for a fortnight, and then these gentlemen will be satisfied ».

But that is more than enough on this absurd topic. […]

![]()

To his father Louis Berlioz (CG no. 160; 10 May)

[…] If these gentlemen of the Institut believe me worthy of obtaining one of the two first prizes, if I can make myself small enough to get through the gate to the kingdom of heaven, I will stay for as short a time as possible in Italy, and from there I will hurry to Karlsruhe, where Haitzinger is normally to be found, or possibly to Dresden, where the famous composer Spohr is Kapellmeister and professes principles altogether more generous than those of composers in Paris. […]

To his sister Nancy Berlioz (CG no. 166; ?16 June)

[…] (Mme Moke is raising objections to the planned marriage of Berlioz with her daughter Camille) So I said to her in reply that my chances of getting the Institut’s prize this year were enormous, and that if I obtained it, a pension of 1000 écus for five years plus that from my father would give me ample time to take advantage of my compositions. That seemed to her far more reasonable, and if I get the prize the duration of our ordeal will be shorter, whether I get permission to stay in France or am obliged to go in exile for a few months in Italy. […]

The Institut’s competition will probably open in the first fortnight of next month. There are two first prizes to be given, so there are twice as many chances, and the voice of public opinion speaks so loudly for me that one has to believe that I will get one at last. I will spare nothing to write them academic music, whatever the subject given. A bad score cannot frighten me at present; to get money, I cannot think of anything I would not do.

But to be locked up for twenty days, twenty days in the company of brutes; twenty days without seeing her!… You will nevertheless be able to visit me every day between 6 and 8. […]

To his mother Joséphine Berlioz (CG no. 168; 16 July)

I am entering the Institut tomorrow; the preliminary competition took place the day before yesterday, we were six, and only six are admitted. Two first prizes will be given, so there are twice as many chances. For a while the extraordinary importance of this competition, because of the position I find myself in, scared me to death, but now that I have tested the ground I am greatly reassured and I am entering my sad prison with some degree of confidence. I was never put to such a test, and this separation, brief as may it be, seems cruel to me. Camille had conceived such a fright, that at times she even dreaded that I might not be admitted to the competition. Although she has assured me a thousand times that the success or failure of my attempt would in no way change her opinion of me, I can nevertheless see that, besides the financial importance and the consequences of the prize for both of us, the mere idea of the glitter that would accrue to me should I be successful upsets her to an extraordinary degree. […]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 169; 24 July)

[…] We have been separated for several days, I am locked in the Institut, for the last time. I must obtain this prize, on which our happiness depends to a great extent; like Don Carlos in Hugo’s Hernani I say: « I will get it ». She torments herself by thinking about it; to reassure me in my prison Mme Moke sends her chambermaid every two days to give their news and get mine. […]

Farewell; I have work to do. I am going to orchestrate the last aria of my scene. The subject is Sardanapalus. […]

To his father Louis Berlioz (CG no. 170; 2 August)

I was the first to come out of the Institut last Thursday [29 July] at 5 o’clock, at the moment when the capture of the Louvre was being completed. The desperate importance of this competition could only keep me for two days fenced in our barricaded fortress, while people were being massacred under our eyes. Gunfire and cannon balls came to us in a straight line, from an artillery position in the Louvre which swept the entire Pont des Arts and reached the doors of the Institut, which as a result are covered with shrapnel. As soon as I had written the last note you can imagine that my first thought was to run to where a mortal anxiety was calling me, traversing the last shots, the screams, the dead, the wounded, etc. Fortunately I found everything as I hoped. After leaving Mme Moke’s, the first but by no means the easiest thing to do was to go and arm myself to try to be of use; so after running around for three hours all I could do was to get hold of a pair of long horse pistols without ammunition.

The national guards sent me to the Hôtel de Ville; I rushed there, no cartridges. Finally, by dint of asking passers-by, I ended up with a complete outfit. I was given a bullet by someone, gunpowder by someone else, a knife to cut the lead by yet another person. Then that is all, not a single fuse was lit. […]

The idea that so many brave people paid with their blood for the conquest of our liberties, while I am among those who were of no use, does not leave me a moment’s rest. It is a new torture, added to so many others…

I am very impatient to have news from you. What is happening in Grenoble? Here everything is quiet, the wonderful order which has prevailed during this magical 3-day revolution continues and takes root; not a single robbery, no outrage of any kind. What a sublime people! […]

To his sister Nancy Berlioz (CG no. 171; 4 August)

[…] Yes, yes, I will get the prize, have no fear. M. Lesueur is over the moon with my cantata; I have done exactly what was required for the Institut. But this prize will only have any worth for me insofar as it makes me obtain Camille, otherwise I will not derive any benefit from it. Her father arrives here on the 25th or 26th of this month; the awarding of the prize will take place on the 21st.

To his mother Joséphine Berlioz (CG no. 172; 23 August)

At last I have the pleasure to announce to you that I have obtained this famous prize. It is mine. Last Thursday the music section gave its preliminary verdict; it had decided that there was no reason to award two first prizes, in spite of their decision of last year, and I had been named the only first prize by a unanimous vote. Last Saturday a meeting of all the sections together began by ratifying the verdict of the musicians for what concerned me, but rather than leaving to the Minister of the Interior the disposal of the funds that had been allocated for last year’s first prize, which had not been awarded, they awarded a second first prize and made happy a poor lad who was certainly not expecting anything of the sort. As a result I was proclaimed first grand prize in the first round of voting, and M. Monfort second grand prize. […]

I only had one opponent, but as he could see that his opposition was in vain he gave me his voice; it is this old jaw of Berton! He was saying last Thursday « that an Academy could not and should not encourage music of the kind I write ». And Heaven knows whether there is anything non-academic in my work. It is a fixed idea with him; I am a Hun who has come to lay waste to the world of music, a kind of revolutionary who must at all costs be held in solitary confinement and guillotined if need be. […] I have been overwhelmed with congratulations and compliments of all kinds, and with fatherly embraces by all these gentlemen. And look at Cherubini’s bonhomie when saying to M. Lesueur: « Heavens, here is a real man; he must have worked terribly hard since last year. » Can you imagine this degree of blindness, to attribute to an excess of work the invention of a few happy melodies, and to believe I have grown in stature when I have shrunk by a half.

But no matter! […]

[See also the letter of Nancy Berlioz to her sister Adèle of 28 August]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 173; 23 August)

[…] It is on the 2nd of October that my scene will be performed in public with full orchestra; my beautiful Camille will be there with her mother; she never ceases to talk about it. This ceremony, which otherwise would have seemed to me a childish amusement, now becomes an intoxicating celebration […]

[…] (His plans for giving concerts) But I need a success at the theatre, my happiness depends on it. Camille’s parents cannot agree to our wedding until this step has been taken. I hope that circumstances will favour me. I do not want to go to Italy; I will go and ask the king to exempt me from this absurd trip and to allow me to draw my pension in Paris. […]<

To his sister Nancy Berlioz (CG no. 176; 5 September)

I had no doubt that the news of my academic prize would cause you pleasure; I am delighted to see that this success is gratifying to all those who are dearest to me. For my part you know what I think of these scholastic distinctions!… But come, let us not speak ill of the academicians, these good folk have been so good to me that it would be ingratitude not to leave them in peace. It seems that I scored an extraordinary success before the venerable assembly, every day I hear truly remarkable reports of the impressions made by my music on the ears of the painters and architects; as far as the musicians are concerned they have conveyed to me in person their satisfaction. Camille who had awaited the decision with so much anxiety, reacted with truly alarming joy when she was informed. […]

[…] her parents are still of the same opinion; it is true that the Institut’s prize has advanced my prospects, but not sufficiently; I need to have a foot in the stirrup, a work on stage at the theatre, in a word my financial situation needs to be more secure. […]

To his sister Nancy Berlioz (CG no. 183; ca. 20 October)

[…] She [Mme Moke] had promised me to come to the Institut with Camille for the prize distribution, but now she is no longer willing; she says they would attract attention, all the musicians would say that she only came for me. As a result this occasion which I was looking forward to as a celebration causes me nothing but pain. Do not pass on to our parents the details I am giving you. […]

To Adolphe Adam (CG no. 186; 25 October)

[…] If you are keen to hear my scene and wish to attend the session, I cannot help warning you, Monsieur, that it is a very mediocre work which by no means represents my deepest musical thoughts; there are very few things in it that I would acknowledge; this score is not up to the current level of music, it is full of commonplace writing and trivial orchestration, but I was forced to write it to secure the prize. If you are good enough to show interest in my compositions, I would rather invite you to come to the Opéra next Sunday, 7 November […]

To his father Louis Berlioz (CG no. 188; 31 October)

The prize distribution of the Institut took place yesterday. I received mine in total isolation. M. Lesueur was ill in bed and unable to attend. Mme Moke stood her ground and refused to put in an appearance. I had neither father, nor mother, nor master, nor mistress, nothing… except a crowd of onlookers attracted by the stir caused by the last rehearsal of my work. This is what happened. After the award of the prize to me, I added a grand piece of descriptive music for the conflagration of the palace of Sardanapalus; I was no longer afraid of the academicians and gave free rein to my imagination. In the midst of the tumult of the conflagration I brought back all the themes of the scene piled one on top of the other; on one side the song of the Bayadères of the first part, but altered melodically and turned into screams of terrified women, and on the other the defiant passage in which Sardanapalus refuses to abdicate his crown; then all this terrifying conflation of cries of pain, shouts of despair, and the proud tones of defiance that even death cannot quell, the hiss of the flames, which ends in the collapse of the palace which silences all the complaints and extinguishes the flames.

I SCORED A FORMIDABLE SUCCESS. I cannot use any other expression.

The final rehearsal took place at the Institut on Friday. For the first time since prizes have been awarded there, the hall was full as on the days of public sessions; but it was full of artists and musicians, and that was the jury I needed. Two other scenes were performed: that of Montfort who won the second first prize, and an Italian piece by a prize-winner who was just back from Rome. They have both been chutés, which is the word used to described polite hissing. At the end of the rehearsal my scene was heard at last; I had made arrangements with the orchestra not to stop but to go through the whole piece without a hitch; everything went well and at the end the audience was dumbstruck by the conflagration. I was overwhelmed with applause, embraced by I know not how many people, carried so to speak all the way to the courtyard of the Institut, in a word had a shattering success. Then in the evening at the Opéra when I arrived, the same thing happened… […]

Now yesterday at the prize distribution where I also scored a great success, at the proclamation of the names, after and during the performance of my scene (the orchestra was interrupted by applause in the middle), can you believe that I had the misfortune of seeing the grand effect of my conflagration ruined? The end, the collapse of the palace, the crowning piece of my fireworks display, something on an immense scale, something novel which is mine and my own invention, that was all lost. The instruments which are supposed to produce this effect have to count pauses before, then go off all at once like a thunderbolt. Well no, they failed to start!… an inconceivable moment of distraction, a fit of panic!… I was with the orchestra, signalled to them to start, but they thought I was making a mistake, they fail to start, the critical bar passes, and it is too late. Oh! there is nothing like it, a deadly rage, I could not contain myself, I flung my score across the orchestra, knocked over the next music stand, and would have massacred everything around had I been able to. […]

![]()

To his father Louis Berlioz (CG no. 649; 11 May)

[…] You have learnt through the papers that I have just been decorated [with the Légion d’Honneur]. If anything can give any value to this banal distinction, it is that I have never said nor asked for anything to be said to demand it. What matters now is securing something from the succession of Paër who has just died. I have thrown my hat in the ring for the Institut, although I do not for one moment expect to get the nomination; they will choose in preference one of my two competitors who have already applied twice. They are Messrs Adam and Onslow. The series of visits I have to submit to is a terrible chore, but I have to go through this route. […]

![]()

To Gaspare Spontini (CG no. 768; 19 March):

[…] Cherubini has just died; so I must now think of the Institut. I have been to see M. Raoul Rochette several times but did not find him; his compatriot M. Champollion, who like him is at the Bibliothèque du Roi [the Royal Library], has just promised me to talk to him and arrange an appointment. But if you were to pick up your pen to prepare the ground with those members of the Institut you know, I would owe you a huge chance of success. The two other candidates are Adam and Onslow. I have against me Carafa and Auber. It is very likely that Halévy, Ingres, Horace Vernet and David will be on my side; Paul Delaroche has committed himself to Onslow but would switch his vote to me if Onslow does not stand a chance. […]

To his father Louis Berlioz (NL no. 773bis; 8 September)

[…] Will you believe that I have not yet been able to make up my mind to pay my visits to the members of the Institut? I have no hope of being nominated, and am discouraged by this obligation of approaching these gentlemen to say:“I have done this and that and would be pleased to have your vote ”. Nevertheless I will take that decision. They will elect Onslow or Zimmerman… or someone else. Victor Hugo presented himself four times to the Académie, and was only admitted at the fourth attempt. A. de Vigny has already failed twice. For me, it is the story of the Prix de Rome all over again! If there was not a pension for life of fifteen or sixteen hundred francs attached to the title of member of the Institut, I confess that the honour of bearing it would not be enough to lure me into making these silly approaches. Besides, it is an honour that has to be shared with a certain number of fools and quite a few mediocrities. […]

To the President of the jury of the Académie des Beaux-Arts (CG no. 786; between late September and late October [Bloom 1981, p. 175])

Please include me among the candidates for the seat which is vacant at the Académie des Beaux-Arts, in the music section.

Here is the list of works I have written to date and which I venture to submit to the appreciation of the Académie […] (there follows a list of 20 titles, with the Requiem in first place)

I do not know whether the Académie will regard as titles in my favour the works of criticism and musical theory which I have been publishing for the last ten years, in the Journal des Débats, in the Gazette Musicale of Paris and Leipzig, and various periodicals; I believe that I should at least own up to them.

Such is, Mr President, the modest body of work that I venture to submit in support of my candidacy; may the Académie not accuse me of presumption or temerity. […]

To the Director of La Sylphide (CG no. 790; between 1 and 10 December) [cf. CM V pp. 231-4]

[…] About the Institut!… Chhhhhhutttt! is it that… and I who… you dont say!… Really?… just as I am telling you. — Well then, tell us about the musicians who do not belong to the Institut! — I do not know any, they all belong to it; so that you should probably throw your hat in the ring at the earliest vacancy that comes up; you will then be lost for your friends who will say philosophically: « It is an academician’s chair that has fallen on his head! » […]

![]()

To James Pradier (CG no. 1382 [see vol. VIII]; 15 February)

[…] Come to my help for the approaching election, as you did twenty years ago for the Prix de Rome. The music section is still opposed to me, and it is very likely that they will not put my name forward. […]

To his brother-in-law Camille Pal (CG no. 1388; 3 March)

[…] I for my part am extremely busy, occupied and absorbed. I am making approaches for the Institut where a seat is vacant because of the death of Spontini. This is only to put down a marker, because it is certain that Ambroise Thomas will be appointed: the entire music section wants it, and the same section is unanimous in not wanting me. Never mind! I put everything out of my mind and go through my academic visits as though it was going to do me some good. [...]

To the members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts of the Institut (CG no. 1389; 6 March)

A vacancy has become available in the music section of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Please include me among the candidates who are applying to obtain it. I include as is customary the list of my works, comprising even those that have not yet been performed in France. […] (a list of 25 titles follows)

And various works of musical criticism to which it may be appropriate to add the foundation of the great Philharmonic Society of Paris, which is currently flourishing and is of real service to art and artists.

Gentlemen, these are my feeble credentials, and please do not compare their worth to that of the immortal works of the great composer we have just lost. […]

To his sister Adèle Suat (CG no. 1392; 17 March)

[…] You know that against my will I have submitted my name for the vacancy at the Institut caused by the death of Spontini; to my great surprise I learned yesterday from a newspaper that the Music Section had put me forward as its third candidate, although this same section is to a man opposed to me. I was expecting not to be put forward at all by it. The fellows did not dare… Never mind, we know from a reliable source that Thomas is going to be appointed. Do you know him?…

The foreigners who happen to be in Paris cannot help laughing at this preference. But that is always the way with the Institut… […]

![]()

To Jules Janin (CG no. 1644; 10 November, from Hanover)

You have been kind enough to offer to intervene with these gentlemen of the Institut; I am sending you herewith the official letter intended for the president of the section. If, as I believe, the time has come to send it to him, could you please look after the matter. I do not know when I will be able to come back to Paris; my concerts are proliferating and following each other from one city to another. […]

To the President of the music section of the Institut (CG no. 1645; 10 November, from Hanover)

A vacancy has arisen in the music section of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Please count me among the candidates who are aspiring to this honour. […] (the letter does not include a list of his works)

To Adolphe Duchène de Vère (CG no. 1653; 19 November, from Bremen)

[…] You have seen how the latest appointment at the Institut was rushed through. I had not yet written that I was submitting my candidacy. Usually the election of a new member only takes place three months after the death of the previous one. Good luck to them! My mind was elsewhere, I was making music, and that usually does not make one think about academies and academicians. […]

![]()

To the President of the Académie des Beaux-Arts (CG no. 1781; 10 August)

The eminently honourable choice that the Académie des Beaux-Arts has just made of an illustrious composer [Halévy] as its permanent secretary creates a vacancy in the music section. I would like to ask you to include me among the candidates who aspire to the honour of filling it. I was in Germany last year when the Academy was busy nominating a successor to M. Onslow, and that was the reason why, not being well informed of the time of the nomination, I sent to Paris my letter announcing my candidacy three days too late. […] (there follows a list of his musical works, his published books, his trips abroad, and his works of musical criticism)

To his sister Adèle Suat (CG no. 1783; 27 August)

[…] You imagine that I am back from Germany. I had to give up the trip to Munich that I was about to undertake, when I heard that there was a vacancy at the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Everyone piled in on me — « You must put aside your self-esteem — you must go on a round of visits like the other candidates — you must persist in applying for every available vacancy — etc, etc. » In the end I resigned myself, and spent a whole week running around Paris from morning to evening to make my calls, certain in the knowledge that someone named Clapisson, who last year obtained 16 votes while I was in Germany, would be elected. As a matter of fact he was elected yesterday with 21 votes. So now I have no choice but to wait for another vacancy and am obliged to persist, since I have started.

This position is worth 1,500 fr, that is all; but it is a great deal for me. I am not speaking of the honour, which is a fiction the moment you admit people such as those who currently are and have always been at the Académie. So far I have only applied twice [three times: 1842, 1851, 1853]. Hugo was obliged to knock five times at the door; De Vigny four times; Eugène Delacroix has not yet been able to gain admittance after six consecutive attempts, and De Balzac never managed to enter. And you will find there a load of cretins…

You have to be resigned to consider this merely as a matter of money, taking part in a lottery, and following your number patiently. I belong to all the Academies of Fine Arts in Europe, except the Académie de France. […]

To Auguste Morel (CG no. 1784; 28 August)

[…] I missed my trip to Munich because of the vacancy which took place at the Institut. I was pushed to throw my hat in the ring, to make visits and approach people as is customary in such circumstances. This I did, and made visits to all the academicians one after the other; and after many fine and flattering words, a warm reception etc., they appointed Clapisson yesterday.

So now on to the next vacancy. I am determined to persist with as much patience as Eugène Delacroix and M. Abel de Pujol who applied ten times. Thomas played a pitiful comedy, which did not fool me for one moment. Reber showed me every possible mark of sincere sympathy and the three other musicians of sincere antipathy.

Halévy worked for me with one hand, but I do not know what his other hand did. They are now thinking seriously of admitting Leborne sooner or later.

You can see that all is well, and that we are progressing along the path of absurdity. […]

To Hans von Bülow (CG no. 1785; 1 September)