![]()

Chronology: 1843, 1853, 1854

The sequel after 1855

The Court Theatre

This page is also available in French

![]()

28 April: Berlioz arrives in Hanover coming from Berlin

6 May: concert in the court theatre

ca. mid-May: Berlioz leaves Hanover for Darmstadt

28 October: Berlioz arrives in Hanover coming from Brunswick

8 November: first concert in the court theatre

15 November: second concert in the court theatre

18 November: Berlioz travels from Hanover to Bremen

26 March: Berlioz departs from Paris in the evening

28 March: Berlioz arrives in Hanover in the morning

29-31 March: daily rehearsals

1 April: concert in the court theatre

2 April: Berlioz travels from Hanover to Brunswick

![]()

Among the early experiences that Berlioz had of Beethoven’s chamber music were performances of the quartets given in Paris in 1830 and 1831 by a quartet led by the violinist Anton Bohrer (1783-1852). Bohrer’s brother Max played the cello part. The two brothers, together with Anton’s wife playing the piano, also introduced the Paris public to some of Beethoven’s trios. Some years later Berlioz alluded to these performances in one of his feuilletons in the Revue et Gazette Musicale (February 1837, cf. Critique Musicale vol. III pp. 33-4), and in his Memoirs he fondly recalled Bohrer’s playing of the quartets in connection with his first visit to Hanover in 1843. Bohrer’s daughter Sophie was also a prodigy piano player, who first performed in Paris with her father in 1838 at the age of nine (cf. Berlioz’s notice in the Journal des Débats, 22 June 1838 [Critique musicale vol. III p. 487]); Berlioz mentions her in the same passage of the Memoirs.

Anton Bohrer became leader of the Hanover orchestra in 1834 and held that position till his death in 1852; his place as leader of the orchestra was then taken by the young Joseph Joachim (see below). It was probably with Bohrer in mind that Berlioz included Hanover on his projected itinerary at the start of his first visit to Germany (Correspondance Génerale no. 791, hereafter CG for short). In January 1843 while in Weimar Berlioz wrote to Bohrer; his letter is not preserved but Bohrer in reply welcomed the approach and started to prepare the ground for Berlioz’s visit, with advice on the choice of hall (the court theatre rather than the more expensive concert hall which the King never attended) and the need to wait till after February (CG no. 809bis [in vol. VIII], 31 January). In the event the visit was delayed till late April, after Berlioz’s concerts in Berlin (CG no. 831, from Magdeburg, 27 April); he arrived in Hanover on 28 April and stayed there till around the middle of May.

The composer’s extant letters give little information on the stay in Hanover, for which the main account is the tenth and final letter in the series Voyage musical en Allemagne, which was first published in the Journal des Débats on 9 January 1844. It was soon reproduced the same year in the first of the two volumes of Voyage musical en Allemagne et en Italie, and was eventually incorporated in the posthumous Memoirs. In truth it was one of the least successful episodes in Berlioz’s first German venture and gave no indication of the warm reception he was to receive there a decade later. Berlioz’s account naturally tries to dwell on the positive aspects of the visit, notably his pleasure at meeting again the Bohrer family and writing about their musical achievements. But there was no disguising the disappointments. Communications with the conductor Marschner were impeded by language barriers. The orchestra included some good players, but was short on strings. It was not possible to have more than two rehearsals, and for the first time in Berlioz’s travels in Germany there was hostility among some players, much to Bohrer’s despair. The concert took place on 6 May (cf. CG no. 833, on the day of the concert [full text in vol. VIII]). Berlioz’s account does not mention the programme in detail, and some uncertainties persist, though the programme can be established from contemporary newspaper reports![]() . It included in that order the King Lear overture, the cantata Le Cinq Mai sung by the bass Steinmüller, the second and third movements from Romeo and Juliet, the songs Le Jeune pâtre breton and Absence sung by Marie Recio, who also sang a cavatina from Benvenuto Cellini after a performance of Harold in Italy in which Anton Bohrer played the solo viola part (cf. CG no. 1621, August 1853). The concert concluded with Berlioz’s orchestration of Weber’s Invitation to the Dance. The results were inevitably lacklustre and the reception by the public cool. On the day of the concert Berlioz wrote from Hanover to his new friend Robert Griepenkerl in Brunswick to thank him for a pamphlet he had just written in his honour, and mentioned briefly in a footnote the evening’s concert (CG no. 833, referred to above): it seems that the letter reached Griepenkerl the same day and still gave him enough time to travel to Hanover to hear the concert. He was not impressed by the difference in standard between Brunswick and Hanover.

. It included in that order the King Lear overture, the cantata Le Cinq Mai sung by the bass Steinmüller, the second and third movements from Romeo and Juliet, the songs Le Jeune pâtre breton and Absence sung by Marie Recio, who also sang a cavatina from Benvenuto Cellini after a performance of Harold in Italy in which Anton Bohrer played the solo viola part (cf. CG no. 1621, August 1853). The concert concluded with Berlioz’s orchestration of Weber’s Invitation to the Dance. The results were inevitably lacklustre and the reception by the public cool. On the day of the concert Berlioz wrote from Hanover to his new friend Robert Griepenkerl in Brunswick to thank him for a pamphlet he had just written in his honour, and mentioned briefly in a footnote the evening’s concert (CG no. 833, referred to above): it seems that the letter reached Griepenkerl the same day and still gave him enough time to travel to Hanover to hear the concert. He was not impressed by the difference in standard between Brunswick and Hanover.

Two days after the concert, on 8 May 1843, Berlioz made the following entry in a notebook he kept with him during his German trip (see the reproduction of the relevant page in Damnation! Berlioz et l’Allemagne [2006] p. 24):

A dismal concert! The orchestra pitifully short of stringed instruments, there are 3 double-basses!! The musicians inclined to stand on their dignity, they cannot be made to hold more than two rehearsals, they have massacred Harold in a truly edifying way. The excellent Bohrer was embarrassed for his orchestra! The public was fairly good.

In the Memoirs Berlioz mentions the presence of the blind Prince of Hanover at the concert, and he was able to talk to him briefly before his departure for Darmstadt. The following year, in August 1844 or not long after, Berlioz apparently sent him a copy of the account of his travels in Germany and Italy which had been published in book form under the title Voyage Musical en Allemagne et en Italie, and the prince rewarded him with the gift of a gold medal (cf. CG no. 946quinquies, 5 March 1845).

Berlioz had subsequently some further contacts with the Bohrer family. The young Sophie eventually came to Paris to display her talents, as Berlioz had hoped, though her arrival was delayed until March 1845 (CG nos. 945, 960). Berlioz had occasion to mention her several times in his articles in the Journal des Débats (29 October and 29 December 1844; 4 March and 29 April 1845; 19 October 1850). But her health was frail and concern for her apparently prevented Anton Bohrer from being present at the Bonn celebrations in honour of Beethoven in August 1845 which he would normally have attended. Sophie later visited Vienna at the time of Berlioz’s stay in early 1846, though it is not known whether Berlioz heard her again at the time. She was to die prematurely in 1851. As for Bohrer’s brother Max, he went on to have a distinguished career as a cellist in his own right and Berlioz was to meet him again during his visit to Moscow in 1847.

_________________________

![]() The evidence comes from Georg Fischer, Opern und Concerte im Hoftheater in

Hannover bis 1866 (Hanover and Leipzig, 1899), p. 160. – Pierre Citron, Calendrier Berlioz (2000), p. 103 states that Berlioz gave two concerts, one early in May and the other on the 6th; there is no evidence for the first concert, and Berlioz in the Memoirs only writes of one concert. – D. Kern Holoman, Berlioz (1989), p. 300-1 states that the Waverley overture was performed, but no evidence is adduced (so too in his Catalogue

of the Works of Hector Berlioz [1987], p. 51), and this piece – unlike his

other overtures – was apparently never conducted by Berlioz himself in any of his concerts in France or abroad (except for the hypothetical performance in Hanover). The

only known evidence consists in fact of the notebook mentioned above, in which Berlioz wrote out part of the second theme of the overture’s Allegro above the comments he made on the concert; most of the other citations from his

works in this notebook coincide with actual performances of the relevant work in particular cities during his trip. But there is as yet no independent confirmation (for example from a programme or review of the concert), and the question must remain open.

The evidence comes from Georg Fischer, Opern und Concerte im Hoftheater in

Hannover bis 1866 (Hanover and Leipzig, 1899), p. 160. – Pierre Citron, Calendrier Berlioz (2000), p. 103 states that Berlioz gave two concerts, one early in May and the other on the 6th; there is no evidence for the first concert, and Berlioz in the Memoirs only writes of one concert. – D. Kern Holoman, Berlioz (1989), p. 300-1 states that the Waverley overture was performed, but no evidence is adduced (so too in his Catalogue

of the Works of Hector Berlioz [1987], p. 51), and this piece – unlike his

other overtures – was apparently never conducted by Berlioz himself in any of his concerts in France or abroad (except for the hypothetical performance in Hanover). The

only known evidence consists in fact of the notebook mentioned above, in which Berlioz wrote out part of the second theme of the overture’s Allegro above the comments he made on the concert; most of the other citations from his

works in this notebook coincide with actual performances of the relevant work in particular cities during his trip. But there is as yet no independent confirmation (for example from a programme or review of the concert), and the question must remain open. ![]()

![]()

It was to be another decade before Berlioz returned to Hanover; he found the position there significantly changed in two respects. The prince of Hanover had taken over as King in late 1851 on the death of his father, and after the death of Anton Bohrer in 1852 the young Joseph Joachim had been appointed leader of the orchestra.

Berlioz remarked in a letter of October 1853 that the King of Hanover had already been well-disposed and gracious to him at a time when he was only Crown Prince (CG no. 1631). Unknown to Berlioz at the time, the visit of 1843 had evidently planted seeds that would grow later, as was also true with the Prince of Hechingen. Mindful perhaps of the reservations expressed by Berlioz in the letter he published in 1843 concerning his visit to Hanover, the young King was anxious after his accession to develop and improve his orchestra by recruiting new players. Berlioz commented more than once on the excellence of the orchestras he conducted in Germany in the 1850s as compared with a decade earlier. There is no recorded contact between the King and Berlioz between 1844 and 1853 (there are in fact no preserved letters between them: all known communications were carried out through third parties). The royal family of Hanover was present at the fateful performance of Benvenuto Cellini at Covent Garden on 25 June 1853 (CG nos. 1609-11, 1617), though there is nothing to suggest any meeting of Berlioz with the King on this occasion. At any rate by September, on his return from concerts in Baden-Baden and Frankfurt, an approach had been made to Berlioz by the King’s manager, Baron von Perglass, inviting him to conduct a concert in Hanover (CG no. 1648). As mentioned above, the orchestra was now led by Joachim.

Berlioz first heard Joseph Joachim (1831-1907) during his stay in Vienna in 1845-1846 and was immediately impressed by the young violin virtuoso, as he mentions in his Memoirs; in a footnote he added later Berlioz wrote ‘Joachim is now the leading violinist in Germany, perhaps in Europe, and an all-round artist’. Part of Joachim’s education took place under the guidance of Mendelssohn in Leipzig, where he had moved in 1843. In 1850 Joachim was appointed leader of the Weimar court orchestra under Liszt; when Liszt mentioned Joachim to Berlioz in a letter Berlioz responded ‘you do not need to recommend Joachim to me, I have known and appreciated him for a long time’ (CG no. 1456, 2 March 1852). Berlioz soon met Joachim in London, who is frequently mentioned in the composer’s correspondence of that year (CG nos. 1462, 1466, 1471, 1491, 1499, 1505, 1538). When in November 1852 Anton Bohrer died his place as leader of the orchestra in Hanover was now taken by the young Joachim. Joachim’s appointment marked the beginning of a close relationship with Berlioz, for whom he was a trusted contact in Hanover for organising the concerts of 1853 and 1854, but also a musician he admired and respected. The Memoirs do not mention this in connection with Hanover (they only refer once to Joachim, in relation to Vienna in 1846), but over a dozen letters from Berlioz to Joachim survive for the period from September 1853 to September 1854.

Because of the absence of the King the planned concert had to be postponed till November (CG nos. 1629-31), and in the meantime Berlioz went to Brunswick where he gave two concerts (on 22 and 25 October), at the second of which Joachim performed a violin concerto and a Paganini caprice. While in Brunswick Berlioz was informed, no doubt by Griepenkerl, of the changes that had taken place in Hanover since his visit of a decade earlier. He writes to Joachim (CG no. 1635 [cf. vol. VIII for the full text], 16 October):

[…] I am also told here that the Hanover orchestra has much improved since I last heard it and that it has more players. […]

Berlioz travelled from Brunswick to Hanover on 28 October, where he stayed at the British Hotel (CG nos. 1636-8), the location of which is not known (he stayed again at the same hotel in 1854: CG nos. 1710, 1714, 1716). The concert took place on 8 November and such was the success that at the request of the King much of the programme had to be repeated at a second concert on the 15th (CG no. 1646, 11 November, to Ferdinand David in Leipzig). The orchestra waived their fee for the first concert as a mark of appreciation, but Berlioz would not accept this for the second (CG no. 1649, to Griepenkerl, 13 November). The venue was the court theatre, as with all the concerts given by Berlioz in Hanover. The programme included the King Lear overture (a favourite of the King, cf. CG no. 2320), parts of the Damnation of Faust (it is not clear which), Le repos de la Sainte Famille which had such a success in Berlioz’s concerts in 1853 (cf. CG no. 1646); the second concert included three of the orchestral movements of Romeo and Juliet. Letters of Berlioz from this period are numerous and give an account which often corresponds closely to the wording of the Memoirs (near the end of chapter 59, dated 18 October 1854), but with more detail. On the 10th Berlioz sent an account of the first concert to Jules Janin in Paris (CG no. 1644):

[…] I do not know when I will be able to return to Paris; my concerts are multiplying and follow each other from one city to the next. I was expecting to give only one concert here, and yesterday morning, after the concert which took place the day before, the King sent for me and requested another concert for Tuesday [15 November].

You must know that as a result of two cruel and improbable accidents the King of Hanover has been completely blind for more than 15 years; that he is also a very distinguished musician, and a highly cultured and artistic man like the King of Prussia. You can therefore imagine the interest he takes in my concerts, so much so that he even comes to rehearsals. Last Monday he stayed with the Queen to hear us work from nine in the morning to one in the afternoon. He showered me yesterday with the most generous compliments, especially on Faust, which he said, caused him almost as much astonishment as surprise. He did not believe that it was still possible to write new music. « And how well you conduct! he added, I cannot see you but I can feel it very well ». When I commented on my good fortune in having such a listener, he replied: « Yes, I owe a great deal to Providence which has granted me a feeling for music in compensation for what I have lost. » The Queen, this charming Antigone, has been no less gracious, and I emerged from the royal audience feeling very happy.

As for the success of my concerts with the public and the musicians, it exceeds by far my wildest dreams. There is shouting, applause, cries of encore! such as you never see in France in spite of the collaboration of the claque. The other day at a rehearsal here my entry was greeted with fanfares from all the wind instruments and applause from the rest of the orchestra, and I found my score covered with crowns.

[…] As for the excellent and devoted orchestras that I can rely on, I do not understand how they can follow me. I know hardly ten words of German, I speak to them in English, they stare at me, I am surprised at their surprise, until I am warned of my misunderstanding and someone translates my words. Fortunately I can always find someone who speaks French […]

A few days later, on 13 November, Berlioz had an unusual visitor: ‘this morning I was visited by Madame d’Arnim, Goethe’s Bettina; as she put it, she had come not to see me but to look at me. She is seventy-two and has plenty of wit’ (CG no. 1648; full text in vol. VIII). Two days after the second concert of 15 November Berlioz wrote to his sister Adèle (CG no. 1651):

[…] There has been the same enthusiasm here [sc. as in Brunswick], with the difference that here this is the first time: when I came to Hanover 11 years ago both the public and the musicians were rather cold. Well, I have found everything changed; I have never heard applause comparable to that on the second evening (the day before yesterday). My scores were covered with crowns and I was called back at the end of the concert with shouting and stamping which caused endless astonishment to our ambassador here.

« You have brought corpses to life, he would say, the public in Hanover is the most frigid in the world; you never see them applauding anything more than twice a year. » The King was my cheerleader. Together with the Queen he insisted on attending every one of my rehearsals. At the last one, on hearing the overture to King Lear, he called me to give me his regards... his regards!... A few days earlier in his palace he had already showered me with compliments. […] You should have seen him the day before yesterday, so excited in his box... and of course, those among his officers and courtiers who have no understanding of music nevertheless feel obliged to imitate him. […]

In the Post-Scriptum of his Memoirs, written in 1856, Berlioz relates in connection with the Love Scene from Romeo and Juliet how ‘one day in Hanover, at the end of this piece, I felt I was being dragged from behind by someone, and on turning round I saw that the players closest to my desk were kissing my coat-tails’. This probably refers either to the concert of 15 November, or to that on 1st April the following year, rather than to the performance in 1843.

A letter to Duchène de Vère on 19 November, when Berlioz was now in Bremen, introduces a less happy note (CG no. 1653):

[…] My fortunes in Germany are going better than they have ever done at any time or place. The enthusiasm of the public’s response is out of this world, and a rather hostile newspaper from Hanover was saying the day before yesterday that Weber, Beethoven and Mozart, German masters gifted with those qualities in which I am deficient, never scored comparable triumphs in Germany. That is precisely what seems to annoy this critic; I no longer have to put up with musical routine but rather with Teutonism, and you know what that is. The musicians in Brunswick have been criticised for giving my name (the name of a Frenchman) to their charitable association for widows, an institution for which I gave a concert. The Hamburg Gazette dealt with this question in a very dignified way and declared that such a reproach was silly, since art does not know any frontiers. […]

The problem was to confront Berlioz in other cities – Brunswick, Leipzig, Dresden – during his German tours of the 1850s.

![]()

The success of the two concerts in 1853 was such that the King insisted that Berlioz return the following year to give another concert. During the winter Berlioz was in correspondence with Joachim about the preparations for it (CG nos. 1672, 1706, 1709). Berlioz left Paris (by train) at 8 pm on 26 March (CG nos. 1708-9, 1712) and arrived on the morning of 28 March; rehearsals started the following day (CG no. 1714, cf. 1715). On 31 March, the day before the concert, Berlioz wrote to Baron Donop in Detmold, one of his most ardent supporters (CG no. 1716; cf. 1717, 1720 [full text in vol. VIII]):

[…] We have just finished here the last rehearsal for the subscription concert in which I was invited to participate. The King insisted that the programme be exclusively composed of my music. We are therefore performing the overture King Lear (at the King’s request); a romance for tenor (Le Jeune Pâtre Breton); the solo for violin entitled Tenderness and Caprice, divinely performed by Joachim; a song (Absence) which M. Nieper was very kind to translate and which is sung to perfection by Mme Nottès; the Queen Mab scherzo and the Love Scene from Romeo and Juliet (at the Queen’s request); and my Fantastic Symphony which had never yet been performed in Hanover. I am unable to convey to you the miraculous precision with which the orchestra plays all this... There is in the Fantastic Symphony an adagio (the scene in the countryside) which is the elder brother of the adagio in Romeo and Juliet. This is the first time that I have heard both works in the same concert. In one of these (the adagio from Romeo) you find the expansiveness of Mediterranean love, the Italian skies, a starlit night… In the other I believe you will recognise the desolation and suffering of northern love, the dark menace of a stormy horizon on a summer evening when silent lightning flashes against the clouds. The former expresses love in the presence of the loved one, the latter love in the absence of the person whom it craves from all nature.

See how simple-minded I am in telling you this... But this morning I was devastated by this contrast and I feel the need to share it with you; I am sure you will not deride my emotion. How I regret that you will not be in the audience tomorrow!… The Queen was at the rehearsal, and after our Shakespearean scene Her Majesty was kind enough to speak words to me which would have pleased you.

Heavens, what an orchestra! how well it understands! what nuances!… what colours!… I can do what I like with it; it feels as though it is my voice that is singing through theirs... […]

Berlioz left for Brunswick the day after the concert. A few days later, on 4 April, he wrote from Brunswick to his uncle Félix Marmion (CG no. 1726):

[…] This time I left Paris to conduct only one of my symphonies at the last concert of the Philharmonic Society of Hanover. When the King heard that I had arrived, he cancelled the singers and players who had been hired for the evening and demanded that the whole programme should be composed of my music. He left me the choice of pieces, with the exception of two which the Queen and he requested: the overture King Lear, and the Love scene from Romeo and Juliet. The queen came to our final rehearsal with her father the Duke of Altenburg. Her Majesty called me after her favourite piece (the adagio from Romeo): « I am very happy to see, she said, that I have not forgotten a note of this wonderful piece, I know it by heart for ever. The King would also have liked to come this morning, and he asked me to say how much he regretted having been detained by a Council meeting over which he had to preside. »

The concert took place the next day before a capacity audience of great distinction. The performance was miraculous and the impact overwhelming, despite the large number of ladies who occupied the centre of the hall (this always tends to cool the public’s response); it was one of my most memorable evenings. On Sunday the King sent for me to offer his compliments. He kept me for an hour and a half. I had to tell him about all the early stages of my musical studies, and my dealings with Paganini. I did not forget to mention, dear uncle, the influence which your musical tastes manifestly had on my childhood instincts for this art, and the lessons you gave me when I was learning my musical ABC. He made me go into the most minute details, and in the end asked me to promise to come back next winter to put on Romeo and Juliet complete in the Hanover theatre: « If we do not have sufficient resources, the King said, we shall summon what you need from Dresden, Brunswick and Hamburg. Talk to my Manager Count von Platen about this. » – I did indeed speak to the Count who for his part worries that the repairs due to be carried out in the theatre this winter will be an obstacle, since I need three weeks of rehearsals. We shall see.

You would have been delighted, dear uncle, to hear at this concert the young violinist Joachim (the King’s concert-master). The elevation and depth of his talent are phenomenal. There is no doubt that at the moment Joachim is the leading violinist in Europe. When he came to rehearse my piece (Tenderness and Caprice) he insisted on playing without music: I know it by heart, he said. And in the event he did not make a single mistake; he performed with a breadth of style, a soul, a tenderness and fantasy which are incomparable, like the peerless musician that he is. He is 23. […]

It will be recalled that Marmion was himself an amateur musician and violin player, as Berlioz mentions in his Memoirs (chapter 3).

While in Brunswick Berlioz was informed by Count von Platen that the King had decided to award him a rare honour, the cross of the Order of Guelphs, to the dismay of the supporters of Marschner, the Kapellmeister of Hanover who no doubt felt overshadowed by Berlioz (CG no. 1725, to Liszt, 4 April; on Berlioz and Marschner cf. also CG no. 2059). The honour proved an unexpected source of irritation to Berlioz: the promised cross did not arrive as promptly as Berlioz expected, and he keeps alluding to the incident in a series of letters that month (CG nos. 1733, 1738, 1744, 1746, 1748, 1750) and later in the year (CG nos. 1789, 1811). The cross was eventually delivered in January the following year (CG nos. 1876, 1889bis [in vol. VIII], 1891).

Meanwhile Berlioz was planning to return to Hanover early in 1855 to perform Romeo and Juliet complete as promised. When in October 1854 Berlioz concluded chapter 59 of the Memoirs he was expecting the performance to take place, and in January 1855 he was preparing to depart at the end of the month (CG nos. 1876, 1881-2). But together with the cross there arrived unexpected news: the King asked him to postpone his trip for a year ‘because of the temporary disarray of his orchestra and chorus’… (CG nos. 1891, 1893; 1 and 7 February).

![]()

Berlioz never had occasion to return to Hanover, but relations remained warm to the end. In 1857 the King of Hanover was one of the royals who subscribed to the edition of the Te Deum (CG no. 2211, 25 February). In October 1858, writing to Baron Donop in answer to queries about the King Lear overture, Berlioz recalled fondly his visits to Hanover: ‘This overture needs a first rate orchestra. I have not heard it since my last trip to Hanover; it is the King’s favourite piece.’ (CG no. 2320). It appears that Berlioz gave to Marie Recio some of the items of jewelry that he had received during his travels from a number of princes. When she died on 13 June 1862 she bequeathed some of that jewelry to Berlioz’s nieces Nancy and Joséphine Suat (CG no. 2627). A letter of the following October to Nancy and Joséphine’s father refers to one item in particular (CG no. 2662):

[…] I must also explain to Joséphine that the shining figure in the coat of arms on the bracelet is that of the King of Hanover (Georgius Rex) GR. You must try to preserve it, he is an excellent prince who has lavished on me proofs of his esteem and interest; Joséphine will probably be pleased to remember this. […]

Correspondence with Joachim did not cease altogether after 1854; the last preserved letter of Berlioz to him dates from January 1859 when Bénazet, the director of the Baden-Baden casino hoped to entice the famous violinist to come to perform at the annual summer festival there, though apparently without success (CG no. 2344). The last mention of Joachim in the correspondence comes as late as 26 April 1865 when Berlioz writes to his friend Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 3001):

[…] The famous German violinist Joachim has come to spend ten days here; he is being asked to perform almost every evening in various salons. I thus heard played by him and by a few other worthy artists Beethoven’s [Archduke] trio in B flat, the [Kreutzer] sonata in A, and the E minor quartet [op. 59 no. 2] …… it is the music of the starry spheres…… you can well imagine and understand that after experiencing such miracles of inspiration, it is impossible to put up with commonplace music, officially sanctioned works, or the pieces recommended by the Mayor or the Minister for Public Education… […]

![]()

The first court theatre was built by Duke Ernst August in 1687-89 next to the palace, at the spot where today the Plenarsaal (assembly room) of the Landtag is located. The last representation in the theatre took place on 27 June 1852; two years later it was torn down. It was here that Berlioz gave his first Hanover concert at 6 May 1843.

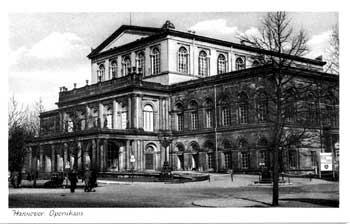

The beautiful new court theatre (nowadays the Opernhaus) which replaced the one next to the palace, was designed by Georg Ludwig Friedrich Laves (1788-1864) and built between 1845 and 1852. It seated 2650 people and was the largest in Germany at the time. It was here that Berlioz gave his concerts of 8 and 15 November 1853 and 1 April 1854. Heavily damaged during World War II in 1943, the exterior of the Opera House was restored in 1950, while the interior was rebuilt after a modern design.

This old engraving is in our collection.

This old engraving is in our collection.

This mid-20th century postcard is in our collection.

We are indebted to our friend Pepijn van Doesburg for this photograph and the history of the Court Theatre.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997.

The page Berlioz in Hanover was created on 1 December 2006. Revised on 1 March 2024.

© (unless otherwise stated) Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb. All rights of reproduction reserved.