![]()

![]()

Introduction

The first visit, November 1845 – February 1846

The second visit, December 1866

Illustrations

See also Berlioz and the Viennese Press, 1845-1846

This page is also available in French

![]()

In the German musical world of the 19th century Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire, held a unique position: among German cities only Berlin could compete. Conscious of her eminence and sophistication Vienna could look back to a series of great composers who had been associated with the city: Gluck, Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert and others. Vienna was thus an inevitable destination for Berlioz sooner or later in the course of his musical travels, though when his travel plans to Germany first emerged in 1832 it was to Berlin that his thoughts initially turned. Interest in Berlioz and his music started to grow in Vienna as elsewhere in Germany in the mid 1830s, prompted by the publication in 1834 of Liszt’s piano transcription of the Symphonie fantastique: in April and May 1835 Berlioz received repeated requests from Vienna to send the (as yet unpublished) full score of the work, but he refused to let his music travel without him (Correspondance Générale nos. 429, 435, cf. 486 in 1836; hereafter CG for short). At the time he was expecting to go to Austria ‘shortly’, though in practice a decade would elapse before this could happen. Contacts continued over the following years: the Francs-Juges overture was performed in Vienna in 1837, as in other German cities (CG nos. 517, 549), and Berlioz had several Viennese correspondents (CG nos. 551, 643). In June 1839 he stated he would visit Vienna before the end of the year (CG no. 655bis [vol. VIII]). Vienna was on the planned itinerary of his first trip to Germany of 1842-1843 (CG nos. 789, 791), but at the time he had no close contacts there (CG no. 794), and in practice the visit to Vienna, like other projected visits, had to be postponed till a later date.

An opportunity arose in August 1845 when Berlioz attended the celebrations in honour of Beethoven in Bonn. His original plan at the time was to travel to Bordeaux after the Bonn celebrations and then to Russia, but a number of Viennese musicians he met in Bonn persuaded him to come first to Vienna (CG no. 992). Berlioz does not identify them further in this letter, though in his report on the Bonn celebrations (Journal des Débats, 22 August and 3 September 1845), which was included later in the Soirées de l’orchestre, he names among other delegates from Vienna Josef Fischoff (1804-1857), professor at the Conservatoire in Vienna, Dr. Joseph Bacher, a wealthy lawyer and music-lover, and the career diplomat and musician Johann Vesque von Püttlingen (1803-1883), all of whom were of considerable assistance in his trip to Vienna. A letter to Josef Fischoff dated 16 October 1845 (CG no. 1002) shows that Berlioz had been in touch with his Viennese contacts after his return from Bonn, and preparations for a lengthy visit which was to include several concerts at the Theater an der Wien were by then well advanced. Berlioz accompanied by Marie Recio eventually departed for Vienna on 22 October, though as he relates in his Memoirs the journey was unexpectedly long and arduous: taken ill and delayed at Nancy, Berlioz then missed the steamer for Vienna at Regensburg and had to proceed by cart to Linz before he could complete the journey to Vienna on the Danube. He did not reach his destination till 2 November.

![]()

1845

2 November: Berlioz and Marie Recio arrive in Vienna

11 November: Berlioz attends a large-scale concert at the Manège

14 November: biographical notice on Berlioz published in Der Zuschauer

16 November: first concert at the Theater an der Wien (Hymn with chorus, with tenor von Behringer [an arrangement for tenor, chorus & orchestra of the Chant sacré from Neuf mélodies (Irlande)]; aria from Benvenuto Cellini, with soprano Mlle von Marra; Harold en Italie, with Heissler as solo viola; Le Cinq Mai, with Staudigl as bass; apotheosis from the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale)

19 November: review of the first concert in Der Zuschauer

23 November: second concert at the Theater an der Wien (first four movements of the Symphonie fantastique; overture Le Carnaval romain; second movement of Harold en Italie; overture King Lear; aria with chorus from Benvenuto Cellini, with tenor Graufeld; chorus of brigands from Lélio, with Staudigl as bass; Marche marocaine by Léopold de Meyer, orchestrated by Berlioz)

26 November: review of the second concert in Der Zuschauer

29 November: third concert at the Theater an der Wien (overture Les Francs-Juges; second movement of Harold en Italie; Le jeune pâtre breton; Le Chasseur danois; Zaïde; overture Le Carnaval romain; first four movements of the Symphonie fantastique)

3 December: review of the third concert in Der Zuschauer

10 December: Berlioz is presented with an honorific silver baton

11 December: a banquet is given in honour of Berlioz’s birthday

17 December: Berlioz participates in a concert (his 4th) given in the hall of the Conservatoire by the pianist Dreyschock, which includes the overture Le Carnaval romain and Le jeune pâtre breton

1846

2 January: fifth concert at the Theater an der Wien: first performance in Vienna of Roméo et Juliette (rehearsed by Berlioz but conducted by the leader Groidl)

4 January: evening reception given by Ernst in honour of Berlioz

5 January: review of the concert on 2 January in Der Wanderer, to which is appended a transcript of a poem by Hofzinser in honour of Berlioz, copies of which were distributed at the concert

5-6 January: review of the concert on 2 January in the Allgemeine Theater-Zeitung

6 January: the Allgemeine Theater-Zeitung reports on the soirée given by Ernst on 4 January

11 January: farewell concert given by Berlioz in the Redoutensaal before his departure for Prague (includes the overture Le Carnaval romain; the second and third movements of Roméo et Juliette; Harold en Italie with Ernst as solo viola); the performance of the singer Pischek causes a sensation

ca. 12 January: Berlioz departs for Prague

13 January: review of Berlioz’s concert on 11 January in the Allgemeine Theater-Zeitung

24 January: the Allgemeine Theater-Zeitung announces Berlioz’s benefit concert on 1 February

28 January: notice in the Allgemeine Theater-Zeitung on Pischek’s performance at the concert on 11 January

29 January: Berlioz returns from Prague to Vienna

1 February: Berlioz gives a benefit concert in the Redoutensaal (includes the overture Le Carnaval romain; the first four movements of the Symphonie fantastique; excerpts from Roméo et Juliette; the second movement of Harold en Italie)

6 February: Berlioz departs for Pesth

22-25 February: Berlioz returns from Pesth to Vienna

ca. 1 March: Berlioz departs for Breslau (Wroclaw)

Berlioz’s stay in Vienna in 1845-1846 is well documented. After his return to Paris he published a detailed account of his second trip to Germany in the Journal des Débats (24 August and 5 September 1847) and in the Revue et gazette musicale (Critique musicale VI pp. 295-305, 307-18, 333-52, 361-98), which eventually found its way into the Memoirs; the first two letters were devoted to Vienna. But unlike the account of the first trip he concentrates on the musical life of the major cities he visited and says relatively little about his own concerts. His correspondence for this period complements the account in the Memoirs though only in part, as the coverage in the preserved letters is uneven – for example no letters survive to record his impressions of the concert on 2 January 1846 when Vienna heard for the first time a complete performance of Roméo et Juliette. A particularly useful insight into the reactions of the musical circles and the general public comes from the contemporary Viennese press: a selection of articles in the original German is reproduced on this site, together with translations by Michel Austin in English and French (the selection leaves gaps and does not include for example the favourable articles by Dr Bacher which Berlioz hoped to get published in French in Paris; cf. CG no. 1009). The press took a very lively interest in his visit, and Berlioz was evidently a talking point in Vienna even before his arrival: when he landed from the steamer the custom’s officer who examined his luggage was very excited. « Monsieur Berlioz, what on earth had happened to you? We have been expecting you for the past week: all our papers announced your departure from Paris and your forthcoming concerts in Vienna. We were very worried at not seeing you. » The ground had evidently been well prepared by his Viennese friends.

Berlioz’s first stay in Vienna differed in several respects from his previous visits to German cities in 1842-43. It was much the longest continuous stay he had made so far in a single place – over two months from 2 November 1845 to 12 January 1846, and he returned twice to Vienna after excursions, first to Prague (ca. 12-28 January) and then to Pesth (6-22 February). He eventually left Vienna ca. 1 March to travel to Breslau (Wroclaw). This prolonged stay enabled him to give a series of concerts (7 altogether) and thus give the public time to become accustomed to his music through repeated performances of his most popular works. He was also able to enjoy the rich musical and social life of Vienna, on which he reports at length in the Memoirs. He was widely fêted, and even posed for portraits (by Prinzhofer and Kriehuber). Most important of all, he found time for composition: he wrote in Vienna the boléro Zaïde, and continued work on his most ambitious undertaking so far, the Damnation of Faust, which he had started before leaving Paris.

Berlioz’s main concerts were given at the Theater an der Wien, not the older and more prestigious Kärntnertor theatre, but the orchestra was augmented by players from elsewhere, including the Kärntnertor; under Berlioz’s direction it grew in confidence and proficiency, and the reaction of the Viennese public was increasingly warm. After the second concert Berlioz wrote on 3 December to the composer Léopold von Meyer, whose Moroccan March he had orchestrated (CG no. 1006):

[…] We have just played here at my second concert your Moroccan March; it was given an outstanding performance and warmly received. The Viennese are very kind to me; they clap furiously and demand up to four encores in one concert

Our Parisians are not so intelligent or enthusiastic. […]

On 16 December he wrote to Desmarest (CG no. 1011):

First the good news; in all likelihood you probably know them already. I am having an enormous success here. They call me back, ask for my music to be played twice or even three times. There is a piece, the overture to Roman Carnival, which the public wanted to hear three times in succession in a concert I was not conducting. Banquets, speeches, crowns, a silver baton offered by the forty leading musicians of Vienna, professionals and amateurs, in short a stunning success. And all this is almost entirely due to our poor Fantastic Symphony: the Scene in the Countryside and the March to the Scaffold have turned the Austrians upside down. As for the Carnival and the Pilgrim’s March they have become popular favourites. Now they are even making pies called after me. I have some excellent musicians, a young orchestra half-Bohemian and half Viennese that I have trained, as it was only assembled two months ago, but is now going like a lion. […]

The Viennese took particularly warmly to the Roman Carnival overture, as Berlioz relates later in his account of his trip to Russia in 1847 (Memoirs ch. 56):

The least successful of my scores in Saint Petersburg was the overture Roman Carnival. On the evening of my first concert it went almost completely unnoticed; count Michel Wielhorski, though an excellent musician, confessed to me that he could not make any sense of it, so I did not perform it again. Say that to a Viennese and he would find it hard to believe. […]

Among all my compositions, the overture Roman Carnival has long been the most popular in Austria, and it was performed everywhere. I remember that during my stay in Vienna it provoked a number of incidents which are worth relating. Haslinger the music publisher was putting on a musical soirée, in which among other pieces this overture was to be performed in an arrangement for two pianos with four hands and a physharmonika.

When it came to this piece in the concert I happened to be close to a door which led to the room where the five performers were. They started the opening allegro much too slowly. The andante went willy nilly. But when they resumed the allegro in an even more languid tempo than at first, I had a rush of blood to the head, turned all bright red, and unable to contain my impatience I shouted: « But this is not the carnival you are playing, but Lent and Good Friday in Rome! » You can imagine the hilarity provoked in the audience by this remark. It proved impossible to restore silence, and in the midst of the laughter and conversations of the listeners the overture ended in unbroken tranquillity. Nothing could shake the unruffled pace of my five performers.

A few days later, Dreyschock was giving a concert in the hall of the Conservatoire, and asked me to conduct this same overture which was in his programme.

« I want to make you forget the Lent of Haslinger’s soirée », he said. He had hired the entire Kärntnertor orchestra. We had only one rehearsal. As we were about to begin one of the first violins who spoke French whispered to my ear: « You are going to see the difference between us and these young rascals from the Theater an der Wien » (Pokorny’s theatre where I was giving my concerts). He was quite right. Never has this overture been performed with more fire, precision, energy, and controlled unruliness. And what a sound from the orchestra! What harmonious harmony! Only this seeming pleonasm can convey what I mean. On the evening of the concert it exploded like a handful of squibs in a fireworks display. The public encored it with shouts and stamping of feet such as you only hear in Vienna.

The reference is to a concert (Berlioz’s 4th) on December 17 given in the hall of the Conservatoire (cf. CG no. 1011, the day before the concert). Dreyschock, a native of Prague like Pischek, is described by Berlioz in his Memoirs (Travels to Germany II, 2nd letter) as « an astonishing pianist, a young, fresh, brilliant and vigorous talent, of immense technical accomplishment and the highest musical sensitivity; he has introduced into his piano music a host of novel and delightfully effective combinations ».

Berlioz’s next concert was one of the most important he gave in Vienna: a complete performance of Roméo et Juliette, the first he had given of the whole work since its creation in Paris in November-December 1839. The work was thoroughly rehearsed (cf. CG no. 1011), and the performance, originally planned for 30 December, eventually took place on 2 January. As may be judged from the two reviews of 5 January and 5-6 January reproduced elsewhere on this site, the critics were evidently taken aback by the novelty of a work which they found complicated and less approachable than what they had hitherto heard from Berlioz, though the reaction of the general public seems to have been more favourable. The story of the Wandering Harpist in the second of the Evenings with the Orchestra gives an indication of this. But the performance was a landmark for the work itself. Berlioz had directed all the rehearsals himself, but unusually he entrusted the conducting of the public performance to the leader of the orchestra, Groidl, while he himself sat in the audience. He was thus able to hear for the first time his work with some detachment, and this led him to make a number of important changes: the two Prologues were reduced to one, which was itself shortened, substantial cuts and changes were made in the Queen Mab scherzo and the Finale, and Berlioz decided to omit from future performances (though not from the full score which was eventually published in 1847) the orchestral movement Romeo at the tomb of the Capulets which many found difficult (CG no. 1034, 16 April 1846, cf. nos. 1017, 1019).

A curious sidelight on Berlioz in Vienna is provided by the first of the two reviews of the concert mentioned above. The critic (Ferdinand Luib) mentions that at the concert copies of a poem in honour of Berlioz by [Johann Nepomuk] Hofzinser were distributed, and the text of the poem was appended by the publisher to the review. A commentary on the poem and the evidence it provides may be found elsewhere on this site; here it may be noted that despite Hofzinser’s friendship with Berlioz his name does not appear to occur in any of the composer’s writings or his correspondence.

Before departing for Prague Berlioz offered to Vienna a farewell concert on 11 January, this time in the large Redoutensaal. Works previously performed were repeated, but the novelty was the participation of the singer Pischek whom Berlioz had previously heard in 1842 and 1843 during his first trip to Germany, and again at Brühl Castle near Bonn in August 1845. Pischek caused a sensation: it is interesting to compare here Berlioz’s account in the Memoirs with the contemporary reviews in the Viennese press. Berlioz’s friend the violinist Ernst also participated in this concert (he played the solo viola in Harold en Italie as well as other pieces); he had recently arrived in Vienna and had organised a soirée in honour of Berlioz on 4 January. On his return from Prague Berlioz organised a final benefit concert on 1 February, again in the Redoutensaal and with a programme drawn from works now familiar to his Viennese audience.

Busy as he was with the preparation of his own concerts Berlioz found time to enjoy Vienna’s rich musical offerings, on which he writes at length in the two letters devoted to Vienna in the Memoirs. Not long after his arrival he was invited to attend (11 November) the first of two annual concerts given in the vast hall of the Manège by a large group of amateur players and singers (over 1000 in all). He gives a detailed account of the event, including an appreciation of the celebrated bass Staudigl, who was to sing at several of his concerts later (including the part of Friar Lawrence in Roméo et Juliette). A few weeks later (on 6 December) he sent a letter of appreciation to the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde [Society of Music-Lovers] (CG no. 1008):

[…] The majesty of the ensemble and the power of the massed forces in this magnificent performance of the three great German masters [Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven] could never obscure the keen harmonic sensitivity which the various orchestral and choral groups displayed and the lucid sense of purpose which guided them through the most challenging difficulties.

It is hard to believe that this vast gathering of a thousand performers is composed almost solely of amateurs. This fact alone demonstrates the wealth of vocal and instrumental talent that Vienna possesses and is enough to guarantee Vienna the musical supremacy over all the capitals of Europe. Such festivals are worthy of the poetic days of antiquity; even to those least gifted by nature in this respect they can convey an idea of the greatness of our art and of the lofty purpose it has set itself. […]

Berlioz also attended performances at the Kärntnertor theatre or concerts given by its musicians in the Redoutensaal – he notes particularly a superb performance of the aria Ozean, du ungeheur (‘Ocean, though mighty monster’) from Weber’s Oberon given by their leading soprano Mme Barthe-Hasselt, whom he compares to the celebrated Mme Branchu of his student years in Paris. A contemporary review confirms his impression, and also mentions the presence of Berlioz and the composer Félicien David at this performance. Berlioz had particular praise for the Kärntnertor orchestra and for its conductor Otto Nicolaï (1810-1849), a composer in his own right and the founder of the Vienna Philharmonic Society:

This orchestra, selected, trained and conducted by Nicolaï has equals but no betters. Apart from the assurance, verve and exceptional technical fluency of their playing, this orchestra produces an exquisite sound, which is probably due to the strict accuracy of the tuning of the instruments as well as to the absence of any faulty intonation in the playing of its individual members […] I regard Nicolaï as one of the best orchestral conductors I have met […] In my view Nicolaï possesses the three essential conditions required for an accomplished conductor. He is an able and experienced composer who has a capacity for enthusiasm; he has a feeling for all the demands of rhythm, and his stick technique is very clear and precise; finally, he is an inventive and tireless organiser who does not spare his time or energy at rehearsals. He knows what he is doing because he only does what he knows. [...]

Another highlight of Berlioz’s stay were the balls organised by Strauss in the Redoutensaal:

The Redoutensaal owes its name to the great balls that are frequently given there during the winter season. The Viennese youth indulges there its sincere and touching passion for dancing, and this has led the Austrians to turn ballroom dancing into a genuine art, as far above the routine of our own balls as the waltzes and orchestra of Strauss are superior to the polkas and scrapers of the dance halls of Paris. I have spent entire nights watching these thousands of incomparable dancers whirling around [...] Strauss is there in person, directing his fine orchestra […] He is a true artist. The influence he has already exerted on the musical taste of the whole of Europe is not sufficiently appreciated. He has introduced into the waltz the interplay of contrary rhythms, which is so effective that the dancers themselves have already tried to imitate him by creating the waltz in duple time, though the music for this waltz still follows a ternary rhythm. […]

Berlioz’s stay in Vienna was in most respects a considerable success. Before he left he was even offered a permanent position as conductor, as he relates to his friend Joseph d’Ortigue some weeks later (CG no. 1028, 13 March 1846; cf. 1029 to his sister Nancy):

[…] The idea has indeed been mooted in Vienna that I should be appointed, not to Donizetti’s post which is not vacant as he is still alive, but to that of Weigl, the director of the Imperial Chapel, who has just died. Someone with considerable influence in the capital of Austria had asked me whether I would accept this position, and I replied that I needed to think it over for a day. This involved a commitment to stay indefinitely in Vienna without the possibility of any annual leave to return to France. I made in this connection a strange discovery, namely that I am so attached to Paris (Paris, that is to say you my friends, the intelligent people who live there, the whirlwind of ideas in which one moves), that the mere thought of being excluded from that made my heart literally sink, and I understood what a torment deportation would be. My answer was therefore a firm negative and I requested that I should not be considered for Weigl’s succession. […]

Despite the warmth of the reception he generally received, there was residual opposition in some quarters. As his second trip to Germany was nearing its end, Berlioz wrote to his friend Robert Griepenkerl in Brunswick (CG no. 1031, 1 April 1846; cf. nos. 1017, 27 January, and no. 1034, 16 April, both to d’Ortigue):

[…] I thank you for all your exertions in spreading our ideas about music. Time is the greatest master of all, and be assured that these ideas will triumph over the whole of northern Germany, and perhaps earlier than we thought; as for the south the matter will soon be concluded. In Vienna arguments are still going on, and there is a recalcitrant minority in the papers which I did not want to flatter or canvass in any way – and the Viennese press loves to find it advantageous to state the case for and the case against. […]

In the summer of 1846 Berlioz had the satisfaction and distinction of being made an honorary member of the Vienna Philharmonic Society (CG no. 1047, 2 July). Late in the year he considered going to Austria on his way to Russia (CG no. 1085bis [in vol. VIII]). But it was to be a full twenty years before Berlioz returned to Vienna.

He maintained some contacts with his Viennese friends, several of whom he mentioned warmly in the second letter on Vienna, first published in the Journal des Débats (5 September 1847; Critique musicale VI pp. 307-18) which he later incorporated in the Memoirs. Not long after his return he wrote to Joseph Fischoff sending him the full score of the Symphonie fantastique and giving musical news from Paris (CG no. 1050, 29 July 1846), but there was apparently little correspondence between the two subsequently: when in March 1853 a pupil of Fischoff performed in Paris, Berlioz described her as ‘a pupil of one of the most excellent teachers in Vienna, my friend J. Fischoff, who in order not to compromise his pupil, had the good sense or self-respect not to write a word to me about her’ (Journal des Débats, 17 March 1853).

Of Dr. Joseph Bacher Berlioz wrote:

Dr Bacher is not a performing musician; he is one of those music-lovers such as only two or three are to be found in Europe. They undertake and sometimes bring to completion the most arduous enterprises, moved solely by the love of music; the purity of their taste lends genuine authority to their public pronouncements, and they often succeed in achieving through their own efforts what rulers ought to be doing themselves but fail to do. Dr Bacher is active, persistent, enterprising and generous beyond words, and in Vienna he is the staunchest supporter of music and a godsend for musicians.

Bacher had been very helpful to Berlioz during his stay in Vienna: as well as writing articles in support of Berlioz, he helped to negotiate terms for the publication of the boléro Zaïde which Berlioz had just composed (CG no. 1018). He wrote to Berlioz in June 1846, though the contents of his letter are not known (CG no. 1946). In the summer of 1849 or 1850 Bacher made a trip to Paris; he visited Berlioz who introduced him to Victor Hugo (CG no. 1270; SD no. 154 [vol. VIII, p. 641], but there is no record of any relations between them after this time.

Berlioz was also warm in his praise of Johann Vesque von Püttlingen:

Councillor Vesque von Püttlingen, who publishes his works under the pseudonym Hoven, provided me with hours of delight by singing his lieder, so felicitous in their melodic turn, so full of humour, and so distinctive in their harmonic accompaniment. I noted the same qualities in the excerpts from two operas he has composed which unfortunately I was only able to hear on the piano.

Vesque von Püttlingen remained for several years Berlioz’s closest friend and correspondent in Vienna: the two men evidently developed a good personal relationship, and Berlioz remembered fondly the warm family environment and welcome that Vesque had provided to him and to Marie Recio during their stay. Over the coming years the two maintained contact steadily and exchanged news (CG nos. 1007, 1016, 1046, 1144, 1394). In November 1847 Berlioz mentioned to Vesque the possibility of performing the Damnation of Faust in Vienna (CG no. 1144), but nothing came of this for the time being. In 1851 Vesque wrote again to Berlioz, sending him an album of melodies; Berlioz responded warmly: ‘I often think of you, and all the signs of affection which you gave me during my stay in Vienna remain present in my mind and dear as though I had received them only yesterday’ (CG no. 1394, 31 March). Not long after Berlioz mentioned the album of melodies favourably in the Journal des Débats (13 April 1851), and the following year he mentioned also the performance of an opera by Vesque at Weimar (11 August 1852). But after this time there is no further trace of any correspondence between the two men.

Nevertheless Berlioz remained in contact with Vienna. The length of his first visit, the numerous concerts he gave there and the impact they had, ensured that subsequently Vienna would continue to show interest in his music. In the summer and autumn of 1855 Berlioz was apparently approached to conduct a series of concerts there, but he seems to have turned down the offer (CG nos. 1995-6, 2029, 2032). In October 1856 he was consulted about a projected performance of the Queen Mab scherzo by the Vienna Philharmonic Society. He sent detailed instructions to the conductor Karl Eckert, who wrote to him after the performance on 7 December, which seems to have been a great success: the scherzo was encored (CG nos. 2181-2, 2190, cf. 2527). In January 1858 the emperor of Austria sent Berlioz a diamond ring on the occasion of the publication of the Te Deum (CG no. 2270).

![]()

October: the Vienna Philharmonic Society invites Berlioz to conduct the Damnation of Faust (initially planned for November, but the performance was postponed till December)

5 December: Berlioz departs for Vienna by train

7 December: Berlioz arrives in Vienna

15 December: final rehearsal

16 December: performance of the Damnation of Faust in the Redoutensaal

17 December: banquet at Hotel Munsch in honour of Berlioz

18 December: Berlioz attends a performance of Harold en Italie by the Conservatoire conducted by Helmesberger

21 December: Berlioz back in Paris

Berlioz’s second visit to Vienna in December 1866 differed from his earlier visit twenty years before. This time it was a shorter one-off trip in response to a specific invitation to give a single performance of one work, the Damnation of Faust: partly composed in Vienna twenty years earlier the Damnation had never been performed there. Any plans of using Vienna as a staging-point for other musical forays in central Europe could not be followed up: Berlioz no longer had the energy and so refused an invitation to give a concert in Breslau (Wroclaw) to follow that in Vienna. The main source of information for the 1866 visit is now the composer’s correspondence which is fuller than for the earlier and longer stay. The Memoirs by now have fallen silent: the concluding page is dated 1 January 1865. Sidelights are provided by the contemporary press (though it remained divided over Berlioz as it had been in 1845-1846; cf. CG nos. 3196, 3198), and also by the recollections of contemporaries: Berlioz’s friend Peter Cornelius, who had himself worked in Vienna in previous years where he championed Berlioz’s cause (CG nos. 2521, 2522, 2594, 2599), came to stay with him in Vienna (cf. CG VII nos. 3187 and 3191, with n. 1 p. 493; Michael Rose, Berlioz Remembered [2001], 270-1); Adolphe Jullien gives some details on the trip in his Hector Berlioz published in 1888 (p. 301-2).

The moving spirit behind the trip was Johann von Herbeck (1831-1877), conductor of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde and a devotee of Berlioz. This in itself was an indication of the long term effect of Berlioz’s first visit of 1845-46. Herbeck had actively promoted his music in Vienna in preceding years. In 1862 he performed Harold in Italy and then the Symphonie Fantastique (CG nos. 2594, 2599, 2605; cf. also no. 2797, in November 1863). In 1864 he organised a performance of Part II of the Damnation of Faust which was scheduled on 11 December to celebrate the composer’s birthday; immediately after the concert he sent a telegram of congratulations to Berlioz to inform him. Berlioz was very touched, as his correspondence shows, and he wrote to Herbeck to thank him warmly: Germany had once more displayed its appreciation of his music (CG nos. 2941-5, 2948-9, 2949bis [VIII]; contrast nos. 2274, 2888). The ground for the invitation of autumn 1866 had thus been well prepared, and Berlioz was offered attractive conditions (contrast CG no. 3107, in March). In October he wrote to his niece Joséphine Suat (CG no. 3174, cf. 3175):

[…] I am leaving for Vienna in Austria on the 9th of next month. The Philharmonic Society has just written to me to invite me to come and conduct my legend of the Damnation of Faust which they want to perform complete for the first time. I will have 200 choristers and 150 players, the best singers from the great theatre, and I will be present at five rehearsals before they hand over the baton to me. So all I will have to do is blow on a fire that has already been lit. These excellent Austrians could not behave in a more generous or artistic way. I am going to meet again a crowd of friends and some very devoted supporters. I have not heard the Damnation of Faust since my last trip to Dresden, more than twelve years ago.

All this is giving me new life, and I am suffering much less. […]

I do not know what I will be given in Vienna by way of expenses and fee, I warned them that I did not want to know and that I would accept with eyes shut. What does it matter? I am too happy to go there and hear again my great score, so bold and to hear it performed without fear or reproach. […]

In the event the performance had to be postponed till December. On 10 November Berlioz wrote to Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 3180, cf. 3178):

Yes, my dear Humbert, I was supposed to be in Vienna; but the other day a message warned me that the concert I was to conduct had to be put back till 16 December, so I will only be leaving on the 5th of next month. I imagine that they feel they have not rehearsed the Damnation of Faust enough to their own satisfaction, and they do not want to present it to me only approximately studied. It is a real joy for me to go and hear this score which I have not heard complete since Dresden twelve years ago. […]

Despite ill health (CG no. 3184) Berlioz eventually left Paris for Vienna on 5 December and arrived two days later: the smooth journey by train was in contrast to the slow trip twenty years earlier by stage-coach, cart and steamer. He was accompanied on his journey by the young Danish musician Asger Hamerik whom he had befriended in Paris and who assisted him as interpreter in Vienna (this fact is known only from Hamerik’s recollections, and not from Berlioz’s correspondence). Berlioz found the rehearsals exhausting (cf. CG nos. 3191, 3192) and contemporaries (Cornelius, Adolphe Jullien) recall several embarrassing incidents when mistakes by the players made Berlioz lose his temper. But the devotion of Herbeck guaranteed success, as Berlioz relates to Berthold Damcke on 13 December (CG no. 3192):

[…] Yesterday and the day before I rehearsed the orchestra on its own, two acts one day and the other two the next day. Today I was in such pain that Herbeck, an incomparable man who knows my score by heart, urged me to stay in bed.

He knew my tempi very well. I am told that he had the first two acts rehearsed to perfection. Tomorrow he will do the same for the following two. The 250 choristers are working like a single man. There is constant applause. […]

In short everything points to a great success. The hall is booked. All the members of the committee are extremely excited. […]

In the event the success of the performance exceeded all expectations, and such was Berlioz’s happiness that he found the energy to write a series of letters to his friends and relatives immediately after the concert and the following day (CG nos. 3194-6, 3198-99, cf. 3206 once back in Paris). The fullest account comes from a letter to Ernest Reyer the day after the concert (CG no. 3200):

[…] The Damnation of Faust, performed yesterday in the vast Redoutensaal before a huge audience, has scored an electrifying success. It would be ridiculous for me to tell you about how often I was called back, the shouts of bis, the flowers, and all the applause of the morning.

I had 300 choristers and 150 players, a delightful Marguerite, the beautiful Miss Bettelheim, who has a superb mezzo-soprano voice, a tenor for Faust (Walter) whose counterpart we certainly do not have in Paris, and a vigorous Mephistopheles, the bass Mayerhofer, all three from the great Vienna Opera. The love duet between Faust and Marguerite, outstandingly sung, was interrupted three times by applause. The scene of the abandoned Marguerite caused an even greater stir. The Sylphs, Wills-o’-the-Wisps, the Easter Hymn, the scenes in Hell and Heaven have literally turned my good audience upside down. Helmesberger (the director of the Conservatoire) gave a most poetic rendering of the little solo for viola in the Ballad of King Thule which Miss Bettelheim sang so well. Since yesterday my room has been overflowing with visitors and well-wishers. This evening they are putting on for me a great reception with two or three hundred guests, professional and amateur musicians, and among them my hundred and forty women choristers (all amateurs) who sang my choruses so well. What fresh and accurate voices! And how well all this was prepared by the director of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Herbeck, a first rate conductor who bent over backwards to assist me and was the first to conceive the idea of putting on my work in its entirety.

Tomorrow I am invited by the Conservatoire, who want me to hear my symphony Harold conducted by Helmesberger.

What can I say to you? It is the greatest musical joy of my life; you must forgive me if I write to you at such length. Some had travelled from Munich and Leipzig to hear the work.

Walter (Faust) has just left, he had come to embrace me again. How he sung the aria in Marguerite’s room and especially the words: « Que j’aime ce silence! » [How I love this silence]

So here is one of my scores that is saved. They will perform it now in Vienna under Herbeck’s direction, and he knows it by heart. The Paris Conservatoire can carry on ignoring me! Let them stay prisoners of their old repertoire.

As in his visit of twenty years earlier Berlioz was very conscious of stepping on the same ground as his mighty predecessor (CG no. 3195):

To think that it is in this same hall that the poor great Beethoven saw his masterpieces coldly received! Time moves on. What shouts! What applause! They are still resounding in my head. […]

At the reception at the Hotel Munsch on 17 December speeches were made including one by the conductor Herbeck (cf. CG VII p. 503 n. 1) and prince Czartoriski (CG nos. 3192, 3206), a devoted patron of music whom he had met in Vienna twenty years earlier. But surprisingly there is no record of any meeting between Berlioz and his erstwhile friend Johann Vesque von Püttlingen, though the latter was alive at the time.

For Berlioz, the special feature of the performance, as that of l’Enfance du Christ in Strasbourg in June 1863, was its scale, both as regards the performers and the audience. « I need large forces and performances on a grand scale; I cannot bear small orchestras, soloists and virtuosos » (CG no. 3211, to his nieces, 11 January 1867). This was in the event the last complete performance of the Damnation of Faust that Berlioz conducted. The memory of the occasion lived on in his mind for months, but the effort involved also left him exhausted (CG nos. 3209, 3211-13, 3227-8, 3234, 3241, 3244). After Vienna the only major trips that remained were a concert in Cologne in February 1867 and his final tour in Russia in winter 1867-8.

Vienna did not forget Berlioz, and performances of his music continued to be given in Vienna after the composer’s death. This forms part of the context for the career of the Viennese-born conductor Felix Mottl (1856-1911) who was to become later the leading champion of Berlioz in Germany in his time.

![]()

Unless otherwise stated, all the pictures on this page have been scanned from documents in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

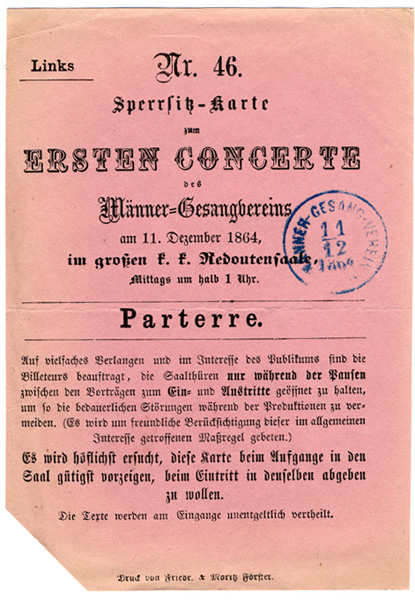

Ticket for the concert on 11 December 1864 at the Redoutensaal at which Part II of La Damnation de Faust was conducted by Johann von Herbeck. A copy of this ticket is in our collection.

During the initial part of his stay in 1845-1846 Berlioz was residing in Fischofstadt (according to CG no. 1011), though the name and location of his hotel is not known. In February 1846 after his return from Prague he stayed at what he calls the « Hôtel de l’Homme Sauvage » (CG no. 1021), again not identified. In December 1866 he stayed at the Frankfurt Hotel (CG no. 3187); according to his friend the composer Peter Cornelius he was in room 49 – Cornelius joined him in Vienna and stayed in room 50 next door (CG vol. VII p. 493 n. 1).

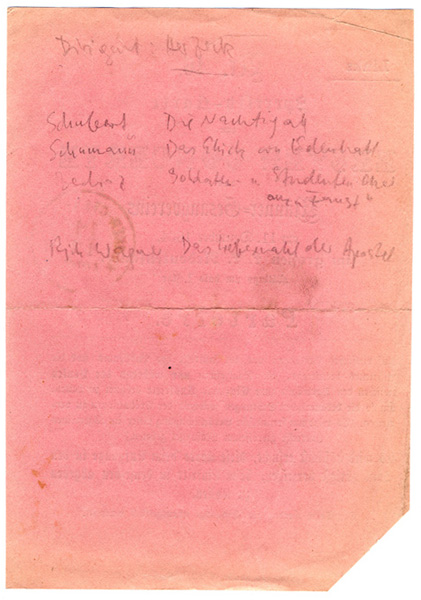

Most of Berlioz’s concerts in 1845-1846 were given at the Theater an der Wien: those on 16, 23 and 29 November, and the performance of Roméo et Juliette on 2 January. Berlioz writes in the Memoirs that the theatre had opened only some three years earlier – this is misleading, since the Theater an der Wien had opened in fact in 1801 (the first two versions of Beethoven’s Leonore were performed there in 1805 and 1806). What Berlioz is referring to is the appointment of the new director Pokorny, under whose management the reputation of the theatre grew apace and came to rival that of the imperial opera at the Kärntnertor theatre. It boasted one of the finest singers of the age in the celebrated bass Joseph Staudigl. The building was constructed in 1797-1801 by Franz Jäger; in 1902 the theatre was altered by the architects Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer.

This picture has been reproduced here courtesy of Adam Carse, 1948, The Orchestra from Beethoven to Berlioz (Cambridge, UK), a copy of which is in our collection.

This 1924 postcard is in our collection.

This part of the building dates from 1902.

This so-called Papageno-gate, which has remained of the original

structure, was formerly the main entrance (see the picture dated 1830 above).![]()

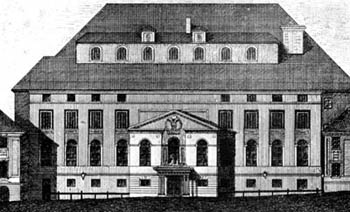

The Redoutensaal was built in 1748 by Jean Nicolas Jadot. After a fire in 1992 it was reopened in 1997 (partly reconstructed, and partly modern). It was in this large hall (it measures 40 x 17 meters) that Berlioz gave his last two concerts in 1846 (on 11 January and 1 February), and conducted the Damnation of Faust on 16 December 1866. In 1845 he also attended many other concerts there. One fact he was always particularly conscious of was that Beethoven had once performed his music there (Memoirs, Travels to Germany II, 2nd letter):

It is in this large and fine hall of the Redoutensaal that thirty years ago Beethoven performed the masterpieces that are now worshipped throughout the whole of Europe, but were received by the Viennese at the time with the most deadly contempt. [...]

[...] My knees were trembling when for the first time I stepped onto the stage on which his mighty feet once trod. Nothing has changed since the time of Beethoven. The rostrum I was using had been his. This was the space occupied by the piano on which he used to improvise. The stairs here leading to the artist’s room were the same he would go down after the performance of his immortal poems, when a few perceptive enthusiasts took pleasure in calling him back with their rapturous applause, to the great astonishment of the other listeners [...]

The vast Redoutensaal is excellent for music. It is a parallelogram, but the angles do not produce any echo. There is only a level floor and a gallery.

This old postcard is in our collection.

The Redoutensaal forms part of the Hofburg complex.![]()

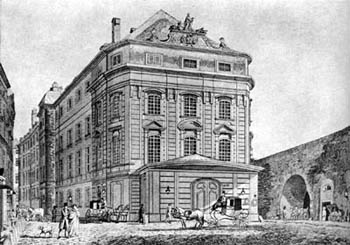

In 1869 the Kärntnertor Theatre was

replaced by the Staatsoper, which is situated immediately in front of the block where the Kärntnertor Theatre used to be.![]()

The Winterreitschule (or Manège) forms part of the Hofburg complex; it was built by Josef Emanuel Fischer von Erlach in 1729-1735. The hall measures 55 x 18 metres.

The Manège is the imposing building second from the right.

The only visible exterior part of the Burgkapelle, which forms part of the Hofburg complex. It was built from 1447 to 1449, and underwent later alterations. Berlioz attended performances of the Imperial Chapel, about which he writes in his Memoirs (see also the 1783 engraving above).

The original villa on these grounds was built in 1815 and altered by the architect Peter Nobile in 1835. The present building at the Rennweg was added in 1846-1848. It now houses the Italian embassy. In 1873 the villa (which was situated east, i.e. right of the present building) was demolished. The property came in the possession of Metternich in 1837 and was then called Villa Metternich.

It was here that Berlioz, defying court conventions, introduced himself boldly to Metternich, some time in early January 1846 before his departure for Prague. The episode is not mentioned in the composer’s correspondence. The visit is related in the third letter of his Travels to Germany II, but only gives a very general outline of the two men’s conversation:

The prince behaved with perfect courtesy, and asked me many questions on the subject of music in general and especially my own, on which it seemed to me that His Highness, who had not yet heard any of it, had formed a very curious idea. I did my best to give him a different one.

It is only in a later passage of the Memoirs that Berlioz clarifies the allusion:

[...] Prince Metternich once said to me in Vienna:

« — Is it you, sir, who compose music for five hundred players? »

To which I replied:

« — Not always, Your Highness, I sometimes write for four hundred and fifty. »

![]()

The page Berlioz in Vienna was created on 1 June 2006, enlarged on 1 December 2014. Revised on 1 April 2024.

We would like to express our thanks to our friend Pepijn van Doesburg for some historical information and photographs of buildings connected to Berlioz in Vienna, and to Professor Stelzel for sending us photocopies of the original articles in German from the Viennese press of 1845-1846.

© (unless otherwise stated) Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb for the text; Pepijn van Doesburg for the photos.

![]() Berlioz and the Viennese press, 1845-1846

Berlioz and the Viennese press, 1845-1846

![]() Back to Berlioz in Germany

Back to Berlioz in Germany