![]()

Conductors: Sir Thomas Beecham (1879-1961)

|

Conductors: Sir Thomas Beecham (1879-1961)

|

|

Introduction

A Mingled Chime

Beecham’s Berlioz repertoire

Beecham’s Berlioz recordings

Hamilton Harty and Beecham

Table of performances

Table of recordings

Illustrations

This page is also available in French

See also three reviews of concerts: Berlioz Reconsidered (February 1936), Beecham leads the Damnation of Faust (April 1936), and A Burst of Berlioz (December 1950).

Beecham = Sir Thomas Beecham, A Mingled Chime. Leaves from an autobiography (London, 1944)

Benson = Tony Benson (ed.), Sir Thomas Beecham, Bart, CH, 1879-1961: Supplement to Maurice Parkes’ Calendar of Sir Thomas’ Concerts and Theatrical Performances, Issue 2 ([Westcliff-on-Sea], 1998)

Gray = Michael H. Gray, Beecham: A Centenary Discography (London, 1979)

Lucas = John Lucas, Thomas Beecham: An Obsession with Music (2008, revised paperback version 2011)

Melville-Mason = Graham Melville-Mason, booklets of CD reissues of BBC recordings of Beecham broadcasts of works by Berlioz (Les Troyens, Harold en Italie, Requiem, Le Roi Lear, Le Corsaire, Marche troyenne)

Parker = Maurice Parker (ed.), Sir Thomas Beecham, Bart, CH, 1879-1961: A Calendar of his Concerts and Theatrical Performances ([Westcliff-on-Sea], 1985) [Note: we have not been able to consult this work]

![]()

Sir Thomas Beecham hardly needs any introduction. A conductor and musician of exceptional talent, a man of great energy, ability and originality, he galvanised the musical world in Britain for over half a century, both in the concert hall and in the opera house. He left a large legacy of recordings, made either in the studio or from broadcast performances, and among his many musical ventures founded two orchestras which lasted after him, the London Philharmonic (founded in 1932 together with Malcolm Sargent) and the Royal Philharmonic (founded in 1946). He also left a rich legacy of anecdotes of varying authenticity; he courted publicity through provocative public pronouncements, as well as through his unconventional behaviour and lifestyle. But behind the façade lay a serious and dedicated musician of exceptional ability. He had a vast and varied musical repertoire, operatic, symphonic and choral, that ranged from the 18th century to contemporary music. A number of composers and works attracted his special attention, notably lesser known French operatic composers of the 18th century (Grétry, Méhul and others), major classical composers such as Handel, Haydn and especially Mozart, one of the loves of his life. Among contemporary composers he showed particular interest in Richard Strauss, Jean Sibelius, and above all Frederic Delius; he was highly regarded by all three as an interpreter of their music. He was a lifelong friend and champion of Delius from 1909 onwards, and in 1959, late in his career, he published a book on him, the only book he wrote on an individual composer (and indeed on any musical topic, apart from his autobiography, A Mingled Chime).

From an early date Beecham was a francophile. Among the many French composers, past and present, who attracted his interest was Berlioz, and Beecham’s name deserves much more than a passing mention in any discussion of those who championed the composer and his music. This page is devoted to Beecham as a Berlioz champion; like other pages on this site that are dedicated to various champions of Berlioz, it does not seek to give a comprehensive view of Beecham’s long and active career, on which much has already been written, but concentrates primarily on what he did for the French composer.

It must be acknowledged at the outset than it does not claim to be more than provisional, because the information we have been able to collect for Beecham’s Berlioz repertoire is less than complete. The material available to us is set out in two tables below.

The first table gives a chronological listing of Beecham’s performances of music by Berlioz over his entire conducting career from 1899 to 1960; though long and detailed it is certainly not complete and ideally needs to be supplemented. We have unfortunately not been able to consult the work which, despite its reported shortcomings, may be presumed to give the fullest collection of evidence available, namely Maurice Parker’s Sir Thomas Beecham, Bart, CH, 1879-1961: A Calendar of his Concerts and Theatrical Performances (Westcliff-on-Sea, 1985). A supplement to this work was published subsequently by Tony Benson, Sir Thomas Beecham, Bart, CH, 1879-1961: Supplement to Maurice Parker’s Calendar of Sir Thomas’ Concerts and Theatrical Performances, Issue 2 (Westcliff-on-Sea, 1998). This corrects errors in Parker’s book and makes substantial additions, but it does not repeat the material presented in the earlier book; it has to be used in conjunction with it, and this we have been unable to do. Some additional information has been provided by several concert programmes in our collection (reproduced below); they range from 1927 to 1949, but constitute only a small fraction of the total, and the same is true of a few reviews of concerts reproduced on this site. All this material gives a probably representative idea of Beecham’s Berlioz repertoire, but it is certainly not complete.

The second table gives a chronological listing of Beecham’s Berlioz recordings; this table is based primarily on Michael Gray’s Beecham: A Centenary Discography (1979) with some additional material from other sources, and it may be presumed to be nearly complete.

The most detailed and up-to-date biography of the conductor that we know of is John Lucas, Thomas Beecham: An Obsession with Music (2008; revised paperback version, 2011). It gives a great deal of varied and discursive information, often anecdotal in character, about Beecham’s life, career and musical activities. But it is of limited help in trying to reconstruct Beecham’s Berlioz repertoire and his views on the composer, beyond the fact that he obviously found him and his music highly congenial (the same applies to the many other composers whose music Beecham performed). The book is almost entirely narrative in character, not analytical; it does not seek to present an overall assessment of Beecham’s achievement, his repertoire, and what he did for individual composers. It mentions numerous performances by Beecham, and sometimes gives more detailed information about some of these, but a very large number are inevitably omitted. There is no concluding chapter to pull together all the many threads that are scattered around in the book. Nor is there a chronological table to enable the reader to form an overall view of Beecham’s eventful career and its major phases. The index is mainly of personal names and reveals gaps. For example, the narrative chapters mention a number of performances by Beecham of Berlioz’s Te Deum between 1909 and 1928 (pp. 41, 51, 119, 184), but none of them figures in the index of performances of Berlioz’s works (p. 367; Beecham also gave other performances of the Te Deum which Lucas does not mention). Important performances of other works by Berlioz are not mentioned, such as Beecham’s 1947 BBC broadcast performance of Les Troyens which was recorded. In all, as regards Beecham and Berlioz, the biography by Lucas is not as informative as are, for instance, those of Felix Mottl by Frithjof Haas or of Hamilton Harty by Jeremy Dibble.

![]()

A convenient starting point for Beecham’s view of Berlioz and his music is Beecham’s own autobiography, A Mingled Chime. It may be worth quoting the statement on the jacket of the original edition of 1944, which, it may be presumed, was printed with the conductor’s sanction. It gives a fair idea of the contents and style of the book:

Sir Thomas Beecham’s long awaited autobiography at last makes its appearance. In language familiar to those who have heard his exquisite impromptu speeches in the concert hall or opera house, Sir Thomas here recounts his musical life from infancy to 1924 in this, the first part of his memoirs.

It is not a record of his private life, but it is a vivid description of his activities as conductor and impresario, as founder of English Orchestras and Opera companies, as friend, collaborator and champion of artists and composers. His great knowledge of art, literature and drama and his superb style will give universal delight. Innumerable incidents are described with flashing humour and sharp wit.

The book will be eagerly read by those who have come under the spell of his magic baton or his unique personality as by those, also, who are interested in the musical world of our century. Devotees of Opera and Ballet, admirers of the music of Delius and all those concerned with the promotion of music will find much of particular interest, while the outspoken way in which he deals with many general questions will amuse and entrance his readers.

The book, with his mastery of style, gives a vivid picture of the dynamic and brilliant personality so well known in English public life.

Beecham himself does not provide any information about when and how he set to writing his autobiography. All he says in the opening chapter (p. 7) is that he resolved to set down nothing that he had not seen or heard for himself; consequently left the writing of the first chapter, about his infancy (1879-1884), to the last. Lucas, while criticising in general terms the accuracy of A Mingled Chime (Lucas p. X) and correcting him on many points in the course of his narrative, does not provide any information on the history of the composition of the work; he merely informs the reader that Beecham dictated the text during the crossing from San Francisco to New Zealand on his way to Australia in late May and early June 1940 (p. 243), and dictated the concluding chapters in October 1942 during his years in the United States (p. 289). The work was thus written during the war years while Beecham was away from England (unlike the first world war of 1914-1918 when he was present in the country throughout). Lucas does not make clear whether Beecham had done any preliminary work on the book before 1940, nor does he mention its actual publication in 1944, and the reception it had, at a time when Beecham was returning to Britain after a long absence from the country during the war. The original 1944 edition states after the end of the final chapter (p. 190) ‘The second and concluding volume of this autobiography will be published as soon as circumstances allow’. No second volume ever appeared, and Lucas does not offer any comment on whether it was ever written, in part or whole.

There are only a few references to Berlioz in A Mingled Chime, but they provide insights into Beecham’s interest in Berlioz. As they are brief, it might be simplest to cite the relevant passages as they appear rather than paraphrase their content.

1. (pp. 20-21; in relation to Charles Hallé and Manchester)

Formerly there were no more than two sorts of virtuosi, the exceptions being so rare as to count hardly at all. The first relegated emotion to a back seat from which there was no danger of its interfering with the calculated operations of technique; and the second gave it free rein to go dashing ahead as contemptuous of its harassed satellite as the North Wind of the obstacles it sweeps from its course. Hallé definitely belonged to the former class, although Berlioz, who had he been an executive artist, would assuredly have been included in the latter, writes of him somewhere as “ce pianiste sans peur et sans reproche”. This is magnificent, but hardly criticism. I know scores of performers who are obviously sans peur, but I should hesitate to apply the rest of the phrase to them; but as for the few who may be deserving of the sans reproche, I usually feel when I hear them that their perfection hangs upon a discretion far too wary to have kindled the enthusiasm of the lively Hector.

2. (p. 34; in 1899 Beecham forms an orchestra in St Helens to give concerts):

At once I realized that here was the medium of musical expression which I had vainly sought in the piano or any other solo instrument. I bought loads of scores, studied them voraciously, and found to my agreeable surprise that I had little difficulty either in grasping their contents or in committing them to memory.

3. (p. 41; in 1900, Beecham is considering his future):

But in [my case] no difficulty of choice [of a career] was present, for I had one definite accomplishment at least — music — and that it had to be in one form or another. For many years I had worked in a general way, and with fair zeal, at the piano, a few other instruments, and the various arts of composition. I had read dozens of text books, histories and biographies, and knew backwards the Grand Traité of Berlioz. It was time to gather up all these loose threads and bind them together in a solid bundle of efficiency.

4. (p. 67; on the level of performance in Birmingham in 1907):

But unfortunately the level of performance [at the Triennial Festival], into which was crowded during three or four days as much new music as the normal ear could absorb in ten, was rarely higher than adequate, as the time and facilities for rehearsal were never anything like sufficient. Over everything hung what Berlioz once described as the fatal disability of all English musical institutions, the curse of the à peu près, and often the proceedings resembled a race meeting more than an artistic celebration.

5. (p. 111; in relation to Delius):

According to Max Chop [a German music critic], Delius belongs to the small group of wholly underivative composers. That is not to say that he is without musical ancestry of any sort, or that his is a greater genius than that of many who are less original in their aesthetic make-up. For instance, the actual musical accomplishment of Mozart is greater than that of Berlioz. But while nearly all that the former master wrote had a definitely pious kinship with the foreshadowing effort of the preceding generation, such extraordinary portents as the Symphonie Fantastique or La Damnation de Faust broke upon the world like some unaccountable effort of spontaneous generation which had dispensed with the machinery of normal parentage. Such human phenomena are invariably more complicated in their mental processes than their more simply constructed brethren of orthodox breed, and can rarely bring themselves to make use of the inheritance bequeathed to them by their predecessors. Theirs is no simple and primitive musical faculty like that of Schubert or Dvořák, each of whom was capable of pouring melody into any form of the art, without the least desire to vary or develop it. Wagner, as we know, saw clearly that Beethoven had said the last word in symphonic structure by stretching it to the furthest possible limits of expansion […].

Chopin, Wagner and Debussy struck out on fresh lines, creating forms for themselves, and Delius is essentially of their kind and company.

In 1897 the young Beecham went up to Oxford (Wadham College), but dropped out before completing the course — he may in fact have been sent down (Lucas pp. 10-12). Very soon he came to the conclusion that his future lay in music, and specifically in conducting. Gifted with a voracious and inquisitive mind he acquired and studied quantities of scores and books on music, among them Berlioz’s treatise on orchestration (above, nos. 2-3). This work was in itself an introduction to Berlioz’s music, as it quotes numerous examples in full score from the composer’s work (as well as those of others). It also contained, in its revised edition of 1855, a supplementary chapter on the art of conducting, which again contains examples drawn from Berlioz’s own music, as well as from his experiences as a conductor. It can be assumed that Beecham acquainted himself early with many of the scores of Berlioz. The second concert he conducted (in 1899, with the Hallé orchestra) contained Berlioz’s Marche hongroise, and works by Berlioz turned up in his concert programmes from 1908 onwards (see the table of performances below). It can also be assumed that Beecham read (in the original French) Berlioz’s books — the composer’s memoirs and his other collections of articles. The two citations from Berlioz (above, nos. 1 and 4) probably both come from a passage in chapter 21 of Les Soirées de l’orchestre, where Berlioz relates his experiences in London in 1851 when he was sent as a member of a jury to adjudicate musical instruments submitted to the Great Exhibition. In the course of his narrative he mentions the work of Charles Hallé in Manchester. Beecham will have known of the Hallé orchestra’s long association with the music of Berlioz which went back to is founder Charles Hallé, a personal friend of the composer. As to the chronic lack of rehearsal time which afflicted British orchestras, and which Beecham noted in Birmingham in 1907 (above, no. 4), it was often commented on by Berlioz in his correspondence.

The passage in which Beecham comments approvingly on Berlioz as a composer and mentions particular works of his (above, no. 5) is the only place in A Mingled Chime where Beecham expresses an opinion on Berlioz’s music. It is implicitly very positive: Beecham evidently appreciated Berlioz’s originality, independence and creative imagination (though he understates Berlioz’s debts to his predecessors, which Berlioz himself freely acknowledged). Yet it is perhaps surprising that Beecham does not say more about Berlioz. One of the features of A Mingled Chime is the profusion of opinions that Beecham dispenses on a wide variety of subjects and persons, above all on music and musicians. Among composers he specifically discusses are (in alphabetical sequence) Granville Bantock (Beecham p. 69), Beethoven (p. 50), Brahms (p. 40), Elgar (pp. 110-11), Delius (pp. 63-4, 70-5, 111-12, 178-9), the 18th century French composers Grétry and Méhul (p. 53), Handel (pp. 65, 68), Joseph Holbrooke (pp. 71, 129), Mozart (pp. 12, 94-5, 111, 126, 155-6), Rimsky-Korsakov (pp. 128), Russian composers in general (pp. 118-19), Schumann (pp. 38-9, 168-9), Ethel Smyth (pp. 84-6), Richard Strauss (pp. 89-90, 96, 112-13, 117), Tchaikovsky (p. 50), Verdi (p. 178), and Wagner (pp. 23-4, 36-7, 114-15, 156-8, 161-2). On all of these Beecham has original views to offer. It is surprising that he has comparatively little to say about Berlioz; he does not mention a single performance of his music given by himself in this period (though he did in fact give a number), and from A Mingled Chime alone one would not have concluded that Beecham regarded himself as a special Berlioz champion.

![]()

The table below gives a chronological listing of those performances of Berlioz by Beecham that are known to us; as explained earlier, it is certainly incomplete and needs to be supplemented, but there is good reason to believe that it gives at least a representative idea of his repertoire.

From this table it emerges that Beecham conducted works by Berlioz frequently throughout his conducting career, from his very beginnings in 1899 down to 1960, the last year he conducted concerts. The only significant gap seems to be from 1916 down to 1922; in 1916 he launched the Opera Company named after himself which took up much of his time and attention until it failed financially in 1920; for a few years Beecham was altogether absent from the podium until he resumed his activities in 1923. Thereafter works by Berlioz figured frequently in his concert appearances.

The table also suggests that for the most part the works he performed most frequently were short orchestral pieces of a predominantly brilliant and extrovert character, at first the Marche hongroise (it had long been a favourite with concerts in Paris before the first world war) and the Carnaval romain overture. To these two Beecham favourites other pieces were added gradually, among them notably the other two orchestral excerpts from La Damnation de Faust (first in 1911), the Chasse royale et orage in 1923 with the Hallé (possibly following the example of Hamilton Harty, who had already performed it with the same orchestra) and the Marche troyenne, also in 1923. After the second world war three more overtures entered his regular programmes, Les Francs-Juges (1945 onwards), Le Corsaire (1946 onwards), and Waverley (1948 onwards). On the evidence set out below it appears that Beecham was, with one exception, relatively slow in performing large scale works by Berlioz: it was not till the 1930s that major works seem to appear for the first time, the Requiem in 1931, the complete Damnation de Faust in 1933, Harold en Italie in the same year, and the complete Symphonie fantastique in 1936. The one exception is the Te Deum, for which Beecham evidently had a special affection: he performed it twice as early as 1909 with the orchestra he had just formed (the Beecham Symphony Orchestra). It was thus heard in London for the first time in many years, and Beecham repeated the work on a number of occasions during his career (1914, 1927, 1928, 1947, 1950, 1953).

Beecham’s Berlioz repertoire, though extensive, showed some large omissions. Among overtures he seems never to have conducted the overtures to Benvenuto Cellini and Béatrice et Bénédict, though both of them, with their contrasted styles, ought to have appealed to Beecham and were popular with other Berlioz conductors (for example Cellini with Felix Weingartner and Béatrice with Hamilton Harty). He appears not to have shown any great interest in Berlioz’s third and fourth symphonies, that is Roméo et Juliette (not even its purely orchestral movements, which were frequently performed separately) and the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale. Among vocal works only one performance of L’Enfance du Christ is known (in 1952), but we have not found any of Tristia (nor even of the great funeral march for the last scene of Hamlet), nor of the songs with orchestra (Les Nuits d’été, La Captive). Beecham says in fact that he hardly ever made use of singers at his concerts (Beecham p. 84).

One other striking gap in Beecham’s Berlioz repertoire is that of the operas. It is one of the ironies of Beecham’s career that despite his devotion to opera as an art form, despite the time, energy and money he spent over three decades in trying to provide England with a national opera, and despite his love of Berlioz, he never in fact performed a single opera by Berlioz on stage. The only work of Berlioz that he did perform on stage was La Damnation de Faust; the work had been conceived by Berlioz as a concert piece and not an opera, though after the composer’s death it became popular on stage thanks to the scenic adaptation by Raoul Gunsbourg. It was first performed in this guise at Monte Carlo in 1893, and spread thereafter elsewhere in Europe. Beecham reportedly believed that La Damnation was best suited to the stage (a view that some will question), and performed it in this form at Covent Garden in 1933, though he did also perform it at other times as a concert work. Of Berlioz’s genuine operas two seem not to have interested Beecham at all, Benvenuto Cellini and Béatrice et Bénédict, though Benvenuto Cellini at least had been popular in Germany ever since the so-called Weimar version was revived in Hanover by Hans von Bülow in 1879. Whatever their considerable musical merits, there is no sign that Beecham ever considered them for performance at any stage of his many operatic undertakings. It seems that he, as many others, found it difficult to think of Berlioz as an operatic composer: in his discussion of operas and opera composers in A Mingled Chime the name of Berlioz is conspicuous by its absence (pp. 50, 119). In relation to Russian opera, Beecham notes that the chorus plays ‘a more prominent and interesting part [in Russian operas] than in the opera of other schools. With few exceptions, such as Lohengrin and Carmen, its employment is casual and fragmentary […] it is rarely an essential and vital element in the drama, while in a Russian opera it is a protagonist with a definite and independent role of its own to play’ (p. 119). It could be argued that in two of Berlioz’s three operas the chorus does play precisely such a role: Benvenuto Cellini and Les Troyens.

Mention of Les Troyens introduces an important qualification to the preceding paragraph. That opera did hold a special place in Beecham’s affections, as shown by his frequent performances of orchestral excerpts from it. It was one of the disappointments of his career that he was not able to fulfill for the whole work the ambitions he had from an early date. Reportedly he dreamed of staging Les Troyens as early as 1910. In 1930 his Imperial League of Opera announced the opera for its forthcoming season, but the whole project fell through. At the end of the 1938-1939 season Beecham announced plans to perform the work at Covent Garden in 1940, but by the end of November 1939 he had agreed on a tour of Australia for the following year. He sailed from Genoa on 10 April 1940 and spent the war years first in Australia, then in North America, from which he only returned at the end of September 1944. On his return he found the operatic scene in London much changed: Covent Garden had now become a state-sponsored theatre in which it would be difficult for him to play a controlling role, and he did not conduct there again until 1951 (Lucas pp. 315-16, 327-8). Beecham had to settle for a studio performance of Les Troyens which was broadcast by the BBC in June 1947 and recorded; excerpts from the opera were broadcast again in February 1949. In 1956 Rafael Kubelik was appointed musical director of Covent Garden, to Beecham’s dismay, and it was he, not Beecham, who conducted the performances of Les Troyens in 1957 and 1958 which came as a revelation to British audiences (see images of this production and the review by Ernest Newman). Very late in his career, at the end of 1959 and in January 1960, Beecham planned to give several concert performances of the opera in the United States (New York, Philadelphia, Washington), but in the event he was only able to conduct those in Washington (9 and 10 January 1960). The remaining ones were conducted by his assistant Robert Lawrence. On his return to Britain Beecham was at long last due to conduct a series of performances of Les Troyens at Covent Garden, starting on his birthday (29 April), but by then he was too ill to take charge (John Pritchard took over) and his old dream remain unfulfilled. He died the following year (1961), coincidentally on the same day as Berlioz himself (8 March).

![]()

The table of recordings below can be assumed to be complete or nearly so, and as such it provides a useful control on the table of performances: all the Berlioz works that Beecham recorded for commercial publication were works that figured in his regular repertoire. Conversely, works that he is not known to have performed in his concerts do not figure either among his recordings: notably the overtures to the operas Benvenuto Cellini and Béatrice et Bénédict as well as the two complete operas, the symphony Roméo et Juliette (not even any of the separate orchestral movements), the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale, Tristia, and the songs with orchestra (especially Les Nuits d’été and La Captive). He did not record either the complete Damnation de Faust (only the 3 orchestral excerpts), or L’Enfance du Christ. Two of his most important Berlioz recordings, the 1947 Les Troyens and the 1959 Requiem, come from broadcasts that were not initially intended for commercial publication and were only issued many years after his death.

One other deduction from the table is how slow Beecham was to record any of Berlioz’s larger works. Before the second world war all his Berlioz recordings are of a limited number of shorter orchestral pieces that were concert favourites of his: the Carnaval romain overture, the Marche hongroise and the other two orchestral excerpts from La Damnation de Faust, and the Chasse royale from Les Troyens. After the war he added the Marche troyenne and also the Lamento from Les Troyens, as well as other overtures he had previously overlooked (Le Corsaire, Le Roi Lear, Waverley). Several of these he recorded on more than one occasion (for instance Le Carnaval romain three times, the Marche troyenne four times).

It was only in the 1950s that came a few of the longer works, Harold en Italie in 1951, the Te Deum in 1953, and the Symphonie fantastique only late in the day, in 1958 and 1959. For comparison Beecham had recorded longer works by other composers well before this time: a complete Beethoven symphony (no. 2) as early as 1926, Handel’s Messiah in 1927, and Gounod’s opera Faust complete in 1929. Unusually for Beecham, the Symphonie fantastique was recorded with an orchestra which was not his own creation: all his previous Berlioz recordings were done with his own orchestras (first the Beecham Symphony Orchestra in 1916, then in the 1930s and briefly in 1945 the LPO, then from 1946 onwards the newly created RPO). But the Fantastique was done with the French National Radio Orchestra, with which he made other recordings in Paris at the same time, notably a complete Bizet Carmen.

The Berlioz recordings give a very vivid idea of Beecham’s style with Berlioz, indeed of his conducting style in general. Beecham gave a description of his own style in a passage in A Mingled Chime which is worth citing in part (pp. 115-16):

Throughout the whole of my career I have been looked upon as the protagonist of rapid tempi¸ in spite of the provable fact that in the majority of cases I have actually taken more time over performance than many of my contemporaries who enjoy the very opposite reputation. […] The truth is that the average ear confuses strong accent and the frequent use of rubato with tempo itself, especially if the accents are varied during the course of a single period, with the result that it has the uneasy sensation of being pricked or speeded against its will. […]

For the full revelation of all that is enshrined in a great orchestral or operatic score, the main essential is the same measure of ease and flexibility that we expect and receive from a solo performer. At the moment there seems to be a struggle between those who favour a rigidly mechanical style of execution, which degrades music from an eloquent language to an inexpressive noise, and those who run to the opposite extremity of a licence that degenerates into anarchy. Surely the truth […] may be found in the just mean […], and approximates to the style of perfect oratory, where a steady and unbroken line of enunciation derives its vitality from a constant variation of inflection and speed which hardly any but the acutest ear is keen enough to follow. In other words, the secret of a persuasive manner is an elasticity of control, so exercised as to give the impression that the iron bonds of rhythm are never seriously loosened.

A more apt description of Beecham’s conducting style could hardly be imagined: his performances of Berlioz and other composers teem with life. It would be impertinent to subject every single recording to a detailed analysis. Beecham is at his best in live performances, which generally show a greater spontaneity than studio recordings, when direct comparisons can be made (such as in the 1953 and 1954 performances of Le Roi Lear, or the 1951 and 1956 performances of Harold en Italie). Beecham is always faithful to the spirit of the music, if not always to its strict letter, and is liable to take liberties if they serve an expressive purpose. This is true in relation to tempi, where he often follows but sometimes diverges from the written indications. He is liable to press on towards the end of fast movements (Le Corsaire, the last movement of Harold en Italie), but sometimes broadens the last few bars for an emphatic final chord (Carnaval romain, Marche troyenne). His practice with repeats fluctuates. He observes the first movement repeat of Harold in the live performance, but omits it in the studio recording. He omits both the first and fourth movement repeats in the Fantastique. In the Te Deum he omits the original 3rd and 8th movements (as unfortunately do most conductors), and in the Christe rex gloriae assigns the passage starting Ad liberandum nos (bar 71) to a solo tenor voice, instead of the tenor voices of the first chorus as in the score. In the Marche troyenne, which he performed with great panache, he regularly made a cut of 26 bars between bars 67 and 93, a cut difficult to justify in a short and brisk piece which is only 167 bars long.

His broadcast performance of the complete Les Troyens is a tantalising document; it has fine moments, great dramatic sweep, and is blessed with a cast of predominantly native French singers with a natural feel for the sound of the language and the marriage of words and music (Marisa Ferrer is among the finest exponents of the role of Cassandra, and is almost as fine as Dido). But the recording quality is baffling, at its best clear and full, but the sound is liable to fade at times to virtual inaudibility, and suffers frequently from obtrusive surface noise. The performance contains a number of cuts, some of them rather rough and arbitrary (such as the truncated orchestral postlude at the end of Act III). On the other hand Beecham made a point of including the orchestral Lamento before the start of Act III which was not part of the original score (it was added by Berlioz for the 1863 performances of the truncated opera), but Beecham evidently had a special fondness for the piece.

It should be added that Beecham could be just as free with other composers he cherished no less. Even with his beloved Mozart he could take liberties: when in 1910 he performed three of his operas at His Majesty’s Theatre he subjected them to numerous cuts and adaptations, and they were a great success (Lucas pp. 62-3; Beecham pp. 94-5 mentions those performances, enthuses about the beauties of Cosi fan tutte, but says nothing about his own changes to the scores). But this was an age when authenticity in performance did not as yet enjoy the importance it was to acquire later.

No such reservations arise with Beecham’s 1959 broadcast of the Requiem. As regards the recording the sound quality is far superior to that of twelve years earlier for Les Troyens, and the performance as a whole is faithful to the score, both its spirit and letter; tempi are in general close to Berlioz’s metronome marks, though the start of the Tuba mirum is taken more briskly than in Berlioz’s score. The 1959 performance in the vast Albert Hall used a smaller chorus than the performance in the Royal Festival Hall the previous year, 148 voices in the RPO chorus as against 275 in the LPO chorus, but it was a professional as opposed to an amateur group. All in all, Beecham’s last recording of a major work by Berlioz is a fitting memorial to Beecham’s work for the composer.

![]()

Born in the same year 1879, Hamilton Harty and Thomas Beecham were almost exact contemporaries (Beecham was a few months older; he was born on 29 April and Harty on 4 December). Beyond being both professional conductors, they shared a good deal of common ground. Both were independent-minded and self-reliant, and achieved their position of eminence through their own abilities and hard work (Beecham rightly insisted that he was no mere amateur: Beecham p. 41). They were not bound by tradition but open to new ideas and new music. In their musical sympathies they both shared a common admiration for Mozart and Berlioz.

But there were also great differences between them. Harty, born at Hillsborogh in northern Ireland, thought of himself as Irish and remained attached to Ireland as a whole; Irish influences were openly displayed in his music (Harty was a composer as well as a conductor, whereas Beecham gave up early his composing ambitions). Harty also came from a relatively modest social background; this limited his opportunities in the early stages of his career. Down to 1900 he had not set foot outside Ireland, and it was only later that he started to travel abroad to continental Europe, though he later developed an international career as well. Beecham for his part was consciously English, though at the same time very cosmopolitan in his culture and attitudes. He came from a wealthy family in Lancashire; the family fortune had been built up by his grandfather’s pharmaceutical business. This gave him opportunities for travel and leisure from an early date. He first visited the US with his father as early as 1893, a country with which he subsequently developed close relations: it was there that he gave some of his last concerts in the early months of 1960. He also started early to make visits to continental Europe, such as a trip to Bayreuth in 1899, and one to Paris in 1904 where he discovered the 18th century French operatic composers. He knew several European languages and was well versed in European culture. He had a public school education at Rossall in Lancashire (1892-1897) then at Oxford (1897-1898). Though he criticised the limitations of public school education with its emphasis on the classics and literature (Beecham pp. 32-3), his education left many traces on him, as may be seen from the rather self-conscious style of his autobiography with its numerous literary allusions.

The two men also differed in personality and temperament. Harty was a quiet and private man who shunned publicity and rarely gave interviews, though he had strong views of his own on musical matters, which he expressed trenchantly (see his 1920 interview). Beecham on his side was much more extrovert and willing to publicise his opinions on a wide range of subjects, musical and non-musical. He made frequent public pronouncements and delighted in attracting attention with provocative statements. Anecdotes about him proliferated.

One major difference between the two men was their attitude to opera. From an early age Beecham was infatuated with the stage: he relates how his love of Mozart was first aroused by his piano teacher who told him about the characters and plots of Mozart’s operas (Beecham pp. 11-12). His first professional engagement as a conductor came in 1902 with a small opera company in Chelsea (Beecham pp. 46-7; Lucas pp. 20-1). The guiding thread of his subsequent career was the ambition to create a permanent opera house in England, and for this he expended vast amounts of time, energy and money. Over his career as a whole he spent at least as much time in the opera house as in the concert hall. Harty by contrast was predominantly an orchestral conductor who had fundamental reservations about opera as an art form. He came late to opera and conducted at Covent Garden for the first time in 1913, by which time Beecham had given numerous performances there, including sensational productions of Richard Strauss’ Elektra and Salome in 1910.

It is not known when the two men first met, but they had dealings with each other in the course of the first world war, when both were active in trying to keep wartime concert activity alive. There is only one short reference to Harty in Beecham’s autobiography, when he relates that he supported the appointment of Harty as permanent conductor of the Hallé orchestra in 1920, a post Harty went on to hold down to 1933 (Beecham p. 176). Beecham makes no further comment on Harty and his abilities, though he evidently judged him suitable for the post. But he does not make any comment on the success of Harty’s subsequent period with the Hallé orchesta. With Beecham’s reticence on Harty one may contrast his detailed account of his relations with another conductor at the time, Landon Ronald (Beecham p. 139).

Beecham was very interested in contemporary composers and their potential; he was noticeably sensitive to national characteristics and how these were reflected in composers’ music. See for example his comments on contemporary English composers (Beecham pp. 42, 70, 110). Of Frederick Delius he writes: ‘Delius was of no decided nationality but a citizen of all Europe, with a marked intellectural bias towards the northern part of it’ (p. 72). Elsewhere he discusses Russian composers and comments on the national characteristics which distinguished them from German, Italian, and French composers (pp. 118-19). In the course of his discussion he mentions the influence of Irish folk melody on Russian composers. Among contemporary Irish composers he makes a few passing references to Charles Stanford, but they reveal little of his views about him (pp. 42, 95, 143). By the time Beecham completed the draft of A Mingled Chime in 1942 Harty was no longer alive, and Beecham was presumably able to express his views on him more freely. But strikingly he makes no comment on Harty as a composer, though Harty’s music was permeated with Irish influences.

Among conductors who championed the music of Berlioz a distinction may be drawn between the ‘selective’ champions and the ‘systematic’ champions. The former admired Berlioz, but only performed and promoted particular works for which they had a special fondness, rather than the composer’s entire output. The latter on the other hand sought to bring to the attention of the public as many of the works of Berlioz as they were able to perform (excluding therefore the works that did not involve orchestral forces). Among conductors a majority of champions of Berlioz fall into the former category; among contemporaries of Beecham Felix Weingartner is a good example, with his predilection for a few particular works (notably the Symphonie fantastique and the overture to Benvenuto Cellini) and his limited interest in the wider Berlioz repertoire. A smaller number of conductors fall into the latter category, notably Édouard Colonne, Felix Mottl, and in more recent times Colin Davis, whose championship of Berlioz has exceeded that of any previous conductor.

Harty’s record as a champion of Berlioz is discussed on the page devoted to him, and it probably justifies placing him in the category of the composer’s ‘systematic’ champions. On his appointment to the Hallé orchestra in 1920 he announced his intention to introduce a series of works by Berlioz to his Manchester audience; he proceeded to do this for over a decade, and acquired a reputation at home and abroad of being a champion of the composer. For example, unlike Beecham, Harty did perform all four of Berlioz’s symphonies. One other feature of his programming was to devote some concerts entirely to the music of Berlioz; one of his concerts was characteristically shared out between the two composers he most admired, Mozart and Berlioz. In the end he was not able to cover the totality of Berlioz’s output. This is partly because his sphere of action was mostly limited to the concert hall, and partly because of his untimely death in 1941, twenty years earlier than his contemporary Beecham.

Beecham’s Berlioz repertoire was discussed above. In comparing him with Harty, one further observation could be added. In the course of his career Beecham did devote some concerts exclusively to composers he particularly admired: for example Haydn and Mozart among established classics, and among contemporary composers Delius, Strauss and Sibelius. But we have not found any example of a concert he devoted exclusively to the music of Berlioz (excepting those large works which filled a whole concert by themselves, such as the Requiem or Les Troyens). It seems therefore that from his record Beecham should be ranged in the category of the ‘selective’ rather than the ‘systematic’ champions of Berlioz, though that does not diminish the importance, quality and brilliance of what he achieved for the great French composer.

![]()

For reasons explained above, the following table of performances by Beecham of music by Berlioz does not claim to be complete; it certainly has significant gaps (particularly as regards concerts in North America), which it is hoped may be filled in due course. But it provides at least a representative idea of Beecham’s Berlioz repertoire. For abbreviations in the rubric Source/Notes see above.

Abbreviations of works by Berlioz: Carnaval = overture le Carnaval romain, Chasse royale = Chasse royale et orage from Les Troyens, Corsaire = overture le Corsaire, Damnation = la Damnation de Faust, Fantastique = Symphonie fantastique, Francs-Juges = overture les Francs-Juges, Lear = Le Roi Lear overture, Marche hongroise = from Damnation, Menuet = Menuet des Follets from Damnation, Valse = Valse des Sylphes from Damnation, Waverley = overture Waverley.

Note also (for the rubric Orchestra):

ABC = American Broadcasting Corporation

BBC = British Broadcasting Corporation

Hallé = Hallé Orchestra

LPO = London Philharmonic Orchestra

LSO = London Symphony Orchestra

RPO = Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

SO = Symphony Orchestra

| Date | Work | Orchestra | Place/Venue | Source/Notes |

| 1899 | ||||

| 6 December | Marche hongroise | Hallé | St Helens, Town Hall | Beecham pp. 34-5; Lucas pp. 13-14; Beecham’s second concert |

| 1908 | ||||

| 4 December | Carnaval | — | Manchester | Benson p. 8 |

| 1909 | ||||

| 22 February | Carnaval, Te Deum | Beecham SO, North Staffordshire Choral Society | London, Queen’s Hall | Melville-Mason; Lucas p. 41-2; first performance of Te Deum in London for 22 years |

| 6 October | Carnaval | Beecham SO | Torquay, Bath Saloons | Benson p. 10 |

| 9 October | Carnaval | Beecham SO | Bournemouth, Winter Gardens | Benson p. 11 |

| 12 October | Carnaval | Beecham SO | Bedford, Corn Exchange | Benson p. 11 |

| 16 October | Carnaval | Beecham SO | St Helens, Town Hall | Benson p. 12 |

| 19 October | Carnaval | Beecham SO | Wigan, New Pavilion | Benson p. 13 |

| 23 October | Carnaval | Beecham SO | Harrogate, Kursaal | Benson p. 14 |

| 28 October | Te Deum | Beecham SO, Wilfrid Hudson, North Staffordshire Choral Society | Hanley, Victoria Hall | Benson p. 15; Lucas p. 51 |

| 1910 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1911 | ||||

| 29 January | Valse, Menuet, Marche hongroise | Beecham SO | London, Alhambra Theatre | Benson p. 20 |

| 10 December | Valse, Menuet, Marche hongroise | Beecham SO | London, Alhambra Theatre | Benson p. 22 |

| 17 December | Marche hongroise | Beecham SO | London, Queen’s Hall | Benson p. 22 |

| 1912 | ||||

| 7 January | Valse, Menuet, Marche hongroise | Beecham SO | London, The Palladium | Benson p. 23 |

| 31 January | Unspecified | Beecham SO | Birmingham | Benson p. 25 |

| 3 November | Marche hongroise | Beecham SO | London, The Palladium | Benson p. 27 |

| 16 December | Carnaval | Beecham SO | Berlin | Benson p. 29; Lucas p. 88 |

| 1913 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1914 | ||||

| 9 October | Carnaval | Hallé | Bradford, St George’s Hall | Benson p. 37 |

| ? | Te Deum | Royal Philharmonic Society, Hallé Choir | London | Lucas p. 119; part of the 1914-15 season of the Royal Philharmonic Society |

| 1915 | ||||

| 11 June | Fantastique movements 2, 4, 5 | New SO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 41; Promenade Concert |

| 15 June | Carnaval | New SO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 42; Promenade Concert |

| 19 June | Troyens à Carthage, Prelude | New SO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 43; Promenade Concert |

| 26 June | Carnaval | New SO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 44; Promenade Concert |

| November | Lear | Royal Philharmonic Society concert | London, Queen’s Hall | Melville-Mason |

| 26 December | Carnaval | Accademia di Santa Cecilia | Rome, Teatro Augusteo | Lucas pp. 127-8; Beecham pp. 144-8 (ch. 31) |

| 1916 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1917 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1918 | ||||

| (8 October) | (Damnation complete) | (Hallé) | (Manchester, Promenade Concerts) | Conducted by Hamilton Harty in place of Beecham (Dibble p. 154 n. 53) |

| 1919 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1920 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1921 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1922 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1923 | ||||

| 15 March | Chasse royale, Marche hongroise | Hallé | Manchester | Hamilton Harty was soloist in his own Piano Concerto |

| 8 April | Chasse royale | LSO and British SO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 63; Lucas pp. 161-2 |

| 11 November | Marche hongroise | LSO and British SO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 64 |

| 13 December | Marche troyenne | LSO | London, Queen’s Hall | Benson p. 64 |

| 1924 | ||||

| 16 February | Carnaval | LSO | Cardiff, Empire Theatre | Benson p. 66 |

| 18 February | Carnaval | LSO | Leicester, De Montfort Hall | Benson p. 66 |

| 19 February | Chasse royale | LSO | Birmingham, Town Hall | Benson p. 66 |

| 22 February | Carnaval | LSO | Sunderland, Victoria Hall | Benson p. 66 |

| 7 March | Chasse royale | LSO | Hanley, Victoria Hall | Benson p. 67 |

| 1925 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1926 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1927 | ||||

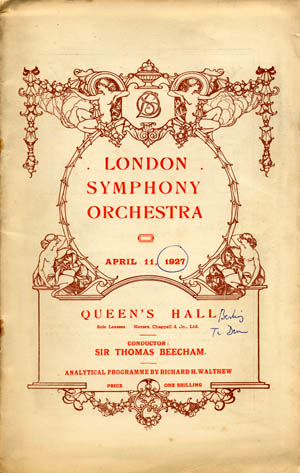

| 11 April | Te Deum | LSO, Walter Hyde, The Philharmonia Choir | London, Queen’s Hall | Concert programme |

| 30 October | Chasse royale | LSO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 73 |

| 1928 | ||||

| January | Chasse royale | New York Philharmonic | New York (U.S.A) | Lucas pp. 177-8 |

| 24 January | Chasse royale | (Philadelphia Orchestra) | Washington (U.S.A) | Benson p. 74 |

| 25 January | Chasse royale | (Philadelphia Orchestra) | Baltimore (U.S.A) | Benson p. 74 |

| 19 February | Chasse royale | LSO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 74 |

| 6 October | Te Deum | LSO | Leeds Triennial Festival | Lucas pp. 183-4 |

| 23 November | Chasse royale | ? | Hastings | Benson p. 80 |

| 1929 | ||||

| 14 September | Marche hongroise | 2RN SO | Dublin, Theatre Royal | Benson p. 82 |

| 1930 | ||||

| (June and September) | (Damnation, staged performance), (Les Troyens) | (Imperial League of Opera) | (London) | Lucas pp. 190-3; Beecham’s projected opera season fell through |

| 1931 | ||||

| 10 October | Requiem | LSO | Leeds Triennial Festival | Lucas p. 200 (Beecham’s first performance of the work; no details provided) |

| 1932 | ||||

| 19 April | Carnaval (?) | Ad hoc orchestra | New York, Metropolitan Opera House | Benson p. 89; Lucas p. 202 |

| 7 October | Carnaval | LPO | Lucas p. 210; Benson p. 92 (first concert by the LPO) | |

| 1933 | ||||

| 20 May | Damnation, Easter Hymn | LPO | London, All Souls’, Langham Place | Benson p. 96 |

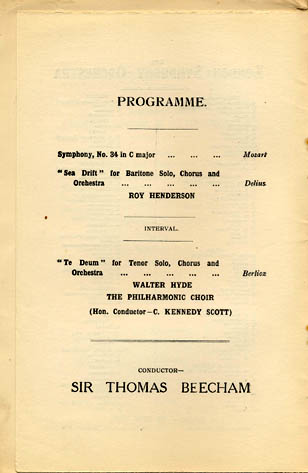

| 26 May | Damnation complete, staged | Royal Opera Covent Garden | London | Concert programme; Lucas pp. 214-15 |

| 18 October | Carnaval | LPO | Bristol, Colston Hall | Benson p. 96 |

| 28 October | Carnaval | LPO | Manchester, Free Trade Hall | Benson p. 97 |

| 29 October | Carnaval | LPO | Bournemouth, Pavilion | Benson p. 97 |

| 3 November | Carnaval | LPO | Liverpool, Central Hall | Benson p. 98 |

| 7 November | Carnaval | LPO | Birmingham, Town Hall | Benson p. 98 |

| Date? | Harold en Italie | LPO, Lionel Tertis (viola) | ? | Melville-Mason |

| 1934 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1935 | ||||

| 30 October | Fantastique, Marche hongroise (encore) | ? | Sheffield | Benson p. 111 |

| 1936 | ||||

| January | Fantastique | Philadelphia Orchestra | New York, Carnegie Hall | See review |

| 17 February | Valse, Menuet, Marche hongroise | LPO | Newcastle-upon-Tyne, City Hall | Benson p. 113 |

| 19 March | Fantastique | Hallé | Manchester | J. Dibble, Hamilton Harty (2013), p. 258 |

| 20 March | Fantastique | Hallé | Bradford | Benson p. 115 |

| 2 April | Damnation complete | LPO | London, Queen’s Hall | See review |

| 5 April | Marche hongroise (encore) | (LPO) | (London) | Benson p. 115 |

| 13 November | Carnaval | LPO | Berlin | Lucas p. 233 |

| 6 December | Carnaval | LPO | Liverpool, Paramount Theatre | Benson p. 118; Concert programme |

| 14 December | Carnaval | LPO | Cardiff, Park Hall | Benson p. 119 |

| 15 December | Carnaval | LPO | Swansea, Brangwyn Hall | Benson p. 119 |

| 1937 | ||||

| 16 March | Carnaval | LPO | Paris, Opéra | Benson p. 120; Lucas p. 235 |

| 20 November | Chasse royale, Marche hongroise (encore) | Derby, Drill Hall | Benson p. 123 | |

| 1938 | ||||

| 15 January | Menuet, Valse, Marche hongroise | LPO | York, Exhibition Buildings | Benson p. 124 |

| 19 January | Marche hongroise (encore) | LPO | Birmingham, Town Hall | Benson p. 125 |

| 24 January | Menuet, Valse, Marche hongroise | LPO | Eastbourne, Winter Garden | Benson p. 125 |

| 29 August | Marche hongroise (encore) | LPO | Glasgow, Concert Hall of Empire Exhibition | Benson p. 129 |

| 30 August | Chasse royale | LPO | Glasgow, Concert Hall of Empire Exhibition | Benson p. 129 |

| 1 September | Chasse royale | LPO | Southport, Floral Hall | Benson p. 129 |

| 3 December | Menuet, Valse, Marche hongroise | LPO | Bristol, Colston Hall | Benson p. 130 |

| 1939 | ||||

| 1 April | Marche hongroise (encore) | LPO | Eastbourne, Winter Garden | Benson p. 132 |

| 16 December | Marche hongroise (encore) | LPO | Bristol | Benson p. 135 |

| 1940 | ||||

| 3 August | Fantastique | Sydney SO | Sydney, Australia | Lucas p. 252 |

| 1941 | ||||

| 4 November | Chasse royale | ? | (High School Concert) (USA) | Benson p. 137 |

| 6 November | Chasse royale | ? | (Broadcast concert) (USA) | Benson p. 138 |

| 1942 | ||||

| Date? | Harold en Italie | Orchestra? William Primrose (viola) | (USA) | Melville-Mason |

| 1943 | ||||

| — | ||||

| 1944 | ||||

| 4 October | Carnaval | LPO | Huddersfield, Town Hall | Benson p. 145 |

| 5 October | Carnaval | LPO | Sheffield, City Hall | Benson p. 146 |

| 7 October | Carnaval | LPO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 146; Lucas p. 307 |

| 10 October | Carnaval | LPO | Bristol, Colston Hall | Benson p. 146 |

| 16 October | Carnaval | LPO | Liverpool | Benson p. 146 |

| 17 October | Carnaval | LPO | Birmingham, Town Hall | Benson p. 146; Lucas p. 307 |

| 18 October | Carnaval | LPO | Nottingham, Albert Hall | Benson p. 146 |

| 19 October | Carnaval | LPO | Leicester, De Montfort Hall | Benson p. 147 |

| 26 October | Carnaval | LPO | Oxford, Sheldonian Theatre | Benson p. 147 |

| 1 November | Chasse royale, Marche troyenne | LPO | Coventry, Central Hall | Benson p. 147 |

| 2 November | Chasse royale, Marche troyenne | LPO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 147; Concert programme |

| 14 November | Chasse royale, Marche troyenne | LPO | Birmingham, Town Hall | Benson p. 147 |

| 15 November | Chasse royale, Marche troyenne | LPO | Leicester, De Montfort Hall | Benson p. 147 |

| 29 November | Chasse royale, Marche troyenne | LPO | Bristol, Colston Hall | Benson p. 148 |

| 1945 | ||||

| 14 April | Marche troyenne | ABC Orchestra | New York (USA) | Benson p. 149; Lucas p. 310 |

| 26 June | Marche troyenne | Liverpool PO | Liverpool | Benson p. 149 |

| 27 July | Chasse royale | LPO | Nottingham, Albert Hall | Benson p. 150 |

| 30 July | Chasse royale, Marche hongroise | LPO | Watford, Town Hall | Benson p. 150 |

| 2 August | Chasse royale, Marche hongroise | LPO | Brighton, The Dome | Benson p. 150 |

| 3 August | Chasse royale, Marche hongroise | LPO | Wembley, Town Hall | Benson p. 150 |

| 4 August | Marche troyenne | LPO | Eastbourne, Winter Garden | Benson p. 150 |

| 9 August | Chasse royale, Marche hongroise (encore) | LPO | Bristol, Central Hall | Benson p. 150 |

| 10 August | Marche troyenne | LPO | Bristol, Central Hall | Benson p. 151 |

| 17 September | Carnaval | LPO | York, Rialto Cinema | Benson p. 151 |

| 28 October | Francs-Juges | LPO | London, Stoll Theatre Kingsway | Concert programme |

| 11 November | Unspecified | Paris Conservatoire Orchestra | London | Lucas p. 312 |

| 24 November | Carnaval | The Scottish Orchestra | Glasgow, St Andrew’s Hall | Benson p. 153 |

| 1 December | Chasse royale, Marche troyenne | The Scottish Orchestra | Glasgow, St Andrew’s Hall | Benson p. 153 |

| 2 December | Francs-Juges | The Scottish Orchestra | Glasgow, St Andrew’s Hall | Benson p. 153 |

| 1946 | ||||

| 12 April | Marche troyenne | Orchestra of the Montreal Festivals | Montreal, Plateau Auditorium (Canada) | Benson p. 155 |

| 12 October | Damnation complete | ? | ? | Benson p. 156 |

| 27 October | Corsaire | RPO | Croydon, Davis Theatre | Melville-Mason |

| 1947 | ||||

| 1 March | Corsaire | Concertgebouw | Amsterdam, Concertgebouw | Benson p. 157 |

| 9 & 13 May | Requiem | RPO | London, BBC Studio 1, Maida Vale | BBC recording |

| 17 May | Te Deum | RPO, Edward Reach, Sheffield Philharmonic Choir | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 158; Concert programme |

| 20 May | Corsaire | RPO | Dundee, Caird Hall | Benson p. 159 |

| 21 May | Corsaire | RPO | Glasgow, St Andrew’s Hall | Benson p. 159 |

| 3 June | Les Troyens (complete) | RPO, BBC Theatre Chorus, soloists | London | BBC broadcast, recorded |

| 10 December | Requiem | BBC SO, René Soames, BBC Choral Society, Luton Choral Society | London, Royal Albert Hall | Concert programme |

| 1948 | ||||

| 9 October | Waverley | RPO | Edinburgh, Usher Hall | Benson p. 163 |

| 11 October | Waverley | RPO | Leicester, De Montfort Hall | Benson p. 163 |

| 12 October | Waverley | RPO | Nottingham, Albert Hall | Benson p. 163 |

| 18 October | Marche troyenne | RPO | Liverpool, Philharmonic Hall | Benson p. 164 |

| 6 December | Waverley | RPO | Manchester, Belle Vue | Benson p. 164 |

| 8 December | Waverley | RPO | Wolverhampton | Benson p. 164 |

| 15 December | Waverley | RPO | London, Royal Albert Hall | (Concert programme, not reproduced here) |

| 1949 | ||||

| 1 February | La Prise de Troie (excerpts), Corsaire | BBC Theatre Orchestra, soloists | London (studio concert) | Benson p. 165 |

| 8 February | Les Troyens à Carthage (excerpts) | BBC Theatre Orchestra, soloists | London (studio concert) | Benson p. 165 |

| 2 May (?) | Unspecified | Liverpool PO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Lucas p. 323 |

| 7 May | Marche troyenne | RPO | Newport, Central Hall | Benson p. 166 |

| 9 May | Marche troyenne | RPO | Swansea, Brangwyn Hall | Benson p. 166 |

| 10 May | Marche troyenne | RPO | Bristol, Central Hall | Concert programme |

| August | Lear | RPO | Edinburgh Festival | Melville-Mason |

| 4 November | Requiem | Montreal SO | Montreal Festival, Canada | Melville-Mason |

| 1950 | ||||

| December | Te Deum | RPO | New York, Carnegie Hall | See review |

| 1951 | ||||

| 3 March | Marche troyenne | RPO | Birmingham, Town Hall | Benson p. 170 |

| 7 March | Corsaire | RPO | London, Royal Albert Hall | BBC recording |

| 9 July | Marche troyenne | RPO | Bristol, Colston Hall | BBC recording |

| November | Harold en Italie | RPO, William Primrose (viola) | London | Melville-Mason; the 1951 recording was made in connection with this concert |

| 1952 | ||||

| August | L’Enfance du Christ | RPO | Edinburgh Festival | Melville-Mason |

| 2 November | Marche troyenne | RPO | Cardiff, Empire Theatre | Benson p. 174 |

| 1953 | ||||

| 8 May | Chasse royale, Marche troyenne | RPO | Oxford, New Theatre | Benson p. 175 |

| Date? | Harold en Italie | RPO, Frederick Riddle (viola) | London | Melville-Mason |

| 2 December | Te Deum | RPO, Alexander Young, LPO Choir | London, Royal Festival Hall | Melville-Mason; the 1953 recording was made after this concert |

| 1954 | ||||

| 8 December | Lear | BBC SO | London, Royal Festival Hall | BBC recording |

| 1955 | ||||

| 23 April | Francs-Juges | RPO | London, Royal Festival Hall | Benson p. 178 |

| 7 May | Les Troyens à Carthage, Prelude; Chasse royale | RPO | London, Royal Festival Hall | Benson p. 179 |

| 3 June | Chasse royale | (RPO) | Bergen (Norway) | Benson p. 179 |

| 2 November | Corsaire | RPO | Manchester, Free Trade Hall | Benson p. 180 |

| 3 November | Corsaire | RPO | Manchester, Free Trade Hall | Benson p. 180 |

| 1956 | ||||

| 31 May | Corsaire | RPO | Paris, Opéra | Benson p. 181 |

| 22 August | Waverley, Harold en Italie | RPO, Frederick Riddle (viola) | Edinburgh Festival, Usher Hall | Melville-Mason; BBC recording |

| 20 December | Lear | BBC SO | London, Studio Broadcast | Benson p. 182 |

| 1957 | ||||

| October | Marche troyenne | RPO | Paris, Salle Pleyel | Lucas pp. 331-2 |

| 1958 | ||||

| 3 December | Requiem | RPO, London Philharmonic Choir | London, Royal Festival Hall | Benson p. 186 |

| 1959 | ||||

| 29 November | Marche troyenne (encore) | RPO | London, Royal Albert Hall | Benson p. 187 |

| 13 December | Requiem | RPO and Chorus, Richard Lewis | London, Royal Albert Hall (BBC broadcast and recording) | Benson p. 188; Lucas p. 336; Melville-Mason |

| 1960 | ||||

| 9 January | La Prise de Troie (concert performance) | American Opera Society Orchestra and Chorus | Washington D.C., Constitution Hall | Benson p. 188; Lucas pp. 336-7; see also Berlioz and the Americas |

| 10 January | Les Troyens à Carthage (concert performance) | American Opera Society Orchestra and Chorus | Washington D.C., Constitution Hall | Benson p. 188; Lucas pp. 336-7; see also Berlioz and the Americas |

| 18 February | Marche troyenne | Seattle Symphony | Seattle | Benson p. 189 (Lucas p. 337) |

| 19 March | Marche troyenne, Corsaire | Chicago SO | Chicago, Orchestra Hall | Melville-Mason; (Benson p. 189; Lucas p. 337) |

| (29 April) | (Les Troyens) | (Covent Garden) | (London, Covent Garden) | Benson p. 189; Lucas p. 337 (Beecham was supposed to conduct the first performance on his birthday, but was unable to do so) |

![]()

The following table has been compiled from the data supplied by Gray’s invaluable discography of Beecham, to which have been added a few non-commercial recordings not listed by Gray, made by the BBC and subsequently published on CD, with informative booklets by Graham Melville-Mason (see above for details). For CD reissues of Beecham recordings of Berlioz, see the section Berlioz Discography.

For abbreviations of musical works by Berlioz and of orchestras see the Table of performances above.

| Date | Work | Orchestra | Company |

| 1916 | Carnaval | Beecham SO | Columbia (acoustic recording) |

| 1916 | Marche hongroise | Beecham SO | Columbia (acoustic recording) |

| 27 November 1936 | Carnaval | LPO | Columbia |

| 12 October & 16 December 1937, 1 February 1938 | Marche hongroise | LPO | Columbia |

| 16 December 1937 | Menuet, Valse | LPO | Columbia |

| 21 November 1938 | Chasse royale | LPO | Columbia |

| 19 January 1945 | Marche troyenne | LPO | Unpublished |

| 24 August & 23 October 1945 | Chasse royale | LPO | HMV |

| 24 August 1945 | Marche troyenne | LPO | HMV? |

| 6 November 1946 | Corsaire | RPO | HMV |

| 3 & 6 June, 2 & 4 July 1947 | Les Troyens (complete, but with some cuts) | RPO, BBC Theatre Chorus, soloists | BBC broadcast, recorded |

| 10 September & 11 November 1947 | Lear | RPO | HMV |

| 7 March 1951 | Corsaire | RPO | BBC broadcast, recorded |

| 9 July 1951 | Marche troyenne | RPO | BBC broadcast, recorded |

| 12, 13, 15 November 1951 | Harold en Italie | RPO, William Primrose (viola) | HMV |

| December 1953 | Te Deum | RPO, Alexander Young, LPO Choir | Philips for Columbia USA |

| December 1953 | Marche troyenne | RPO | Philips for Columbia USA |

| 2-3 December 1953 | Waverley, Lear, Corsaire | RPO | Philips for Columbia USA |

| 8 December 1954 | Lear | RPO | BBC broadcast, recorded |

| 16 December 1954 | Les Troyens à Carthage, Prelude | RPO | Philips for Columbia USA |

| 16 December 1954 | Carnaval | RPO | Philips for Columbia USA |

| 17 December 1954 | Francs-Juges | RPO | Philips for Columbia USA |

| 22 August 1956 | Harold en Italie | RPO, Frederick Riddle (viola) | BBC broadcast, recorded |

| 23 March 1957 | Chasse royale | RPO, Beecham Choral Society | HMV |

| 25 March 1957 | Valse, Menuet | RPO | HMV |

| 8-9 November 1957, 14 May 1958 | Fantastique | French National Radio Orchestra | HMV |

| 19 November 1959 | Marche troyenne | RPO | HMV |

| 30 November, 1-2 December 1959 | Fantastique | French National Radio Orchestra | HMV |

| 13 December 1959 | Requiem | RPO and Chorus, Richard Lewis | BBC broadcast, recorded |

![]()

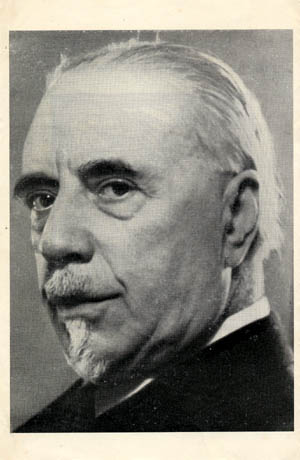

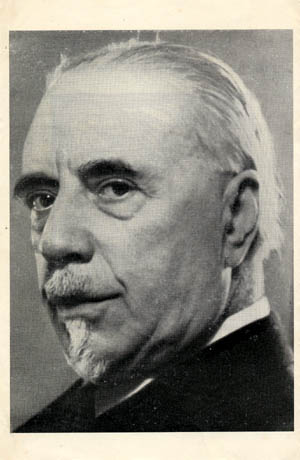

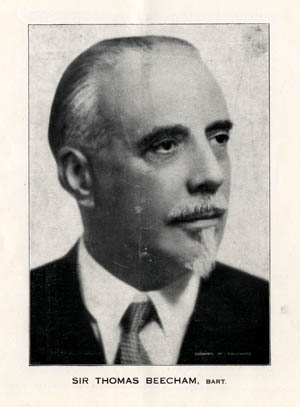

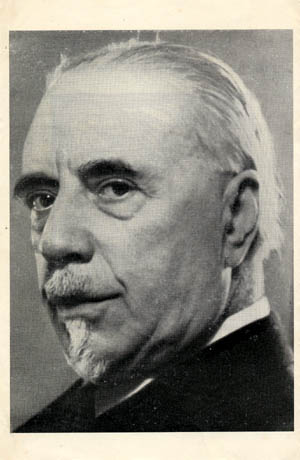

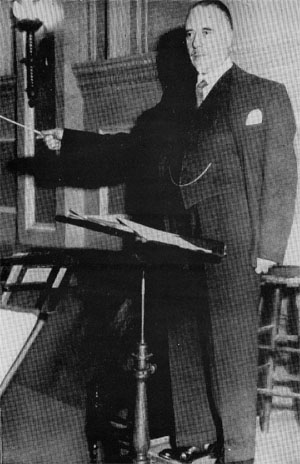

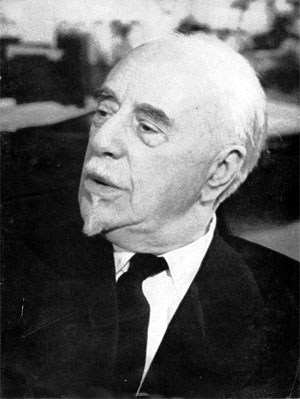

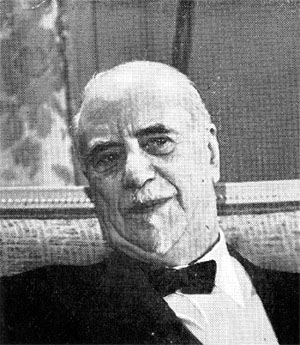

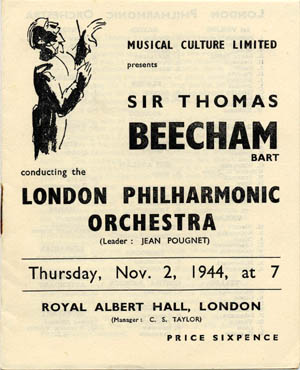

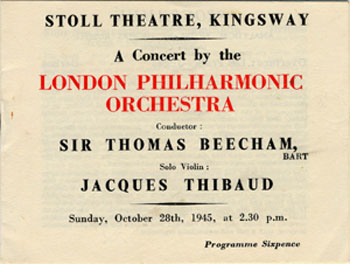

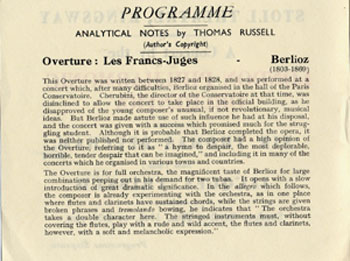

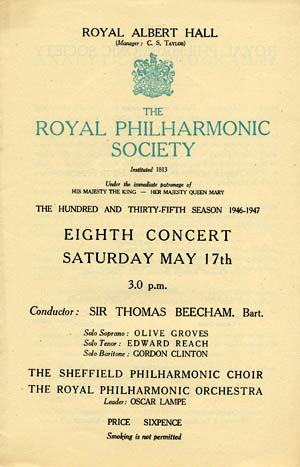

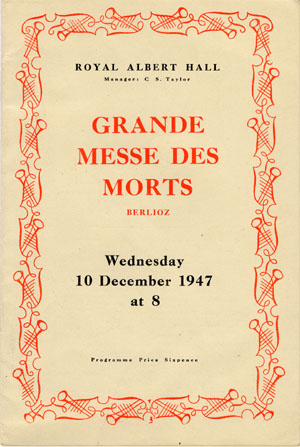

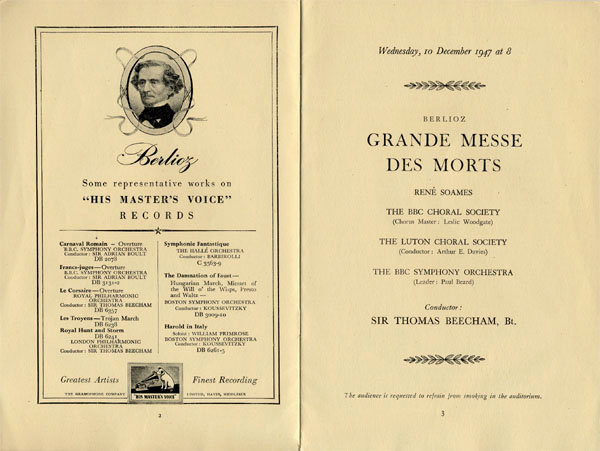

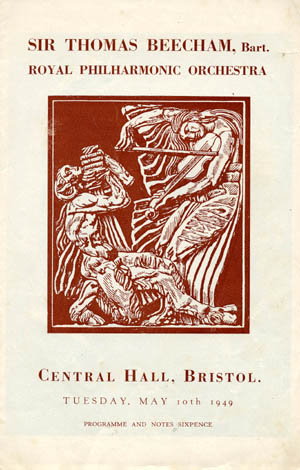

The first two portraits and all the concert programmes reproduced below come from our own collection.

This portrait is taken from the concert programme of 6 December 1936 reproduced below.

This portrait is taken from the concert programme of 10 May 1949 reproduced below.

Among Berlioz’s larger works Beecham had a special liking for the Te Deum; he performed it as early as 1909, then on a number of occasions subsequently: 1914, 1927 (this performance), 1928, 1947 (see below), and 1950. He recorded the work after a performance in 1953.

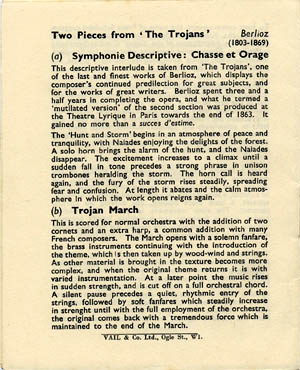

The 3 orchestral pieces from La Damnation de Faust figured frequently in Beecham’s concerts, especially the Marche hongroise, which he often performed as an encore (see the Table of performances). He gave a number of performances of the complete work as a concert piece (for example 1936 and 1946), but reportedly believed that the work should ideally be performed in the theatre (Lucas pp. 214-15), as it was in this 1933 performance at Covent Garden.

Beecham had founded the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1932. The portrait of Beecham reproduced above is taken from this programme.

This was one of a series of concerts with the LPO which Beecham gave on his return from the United States at the end of September 1944 (during the war he was in Australia in 1940, then in the United States and Canada down to 1944). The Chasse royale et orage and Marche troyenne were two favourite pieces of Beecham which he frequently included in his concerts, the Chasse royale from 1923 onwards and the Marche troyenne from 1944 onwards (see the table of performances above). He made recordings of both works (see the table of recordings).

Beecham made a recording of Les Francs-Juges later, in 1954 (see Table of recordings).

On Beecham and the Te Deum see above.

Beecham first performed Berlioz’s Requiem in 1931, and on a few occasions subsequently (3 times in 1947, including this performance, and in 1958 and 1959). Fortunately his last performance, in 1959, was recorded as well as broadcast by the BBC.

The Berlioz item in this concert was the Marche troyenne, an arrangement by Berlioz himself of music from Les Troyens, and a regular favourite of Beecham at his concerts (see also above). The second portrait of Beecham above is reproduced from this concert programme.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir

Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997;

Page Berlioz: Pioneers and Champions created on 15 March 2012; this page created on 1st August 2020.

© (unless otherwise indicated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights reserved.