This page is also available in French

The Symphonie fantastique has long been the best-known and most frequently performed of Berlioz’s major works, though it may well owe its popularity as much to the programme that Berlioz attached to the symphony and its autobiographical associations, as to its own considerable musical merits. The work was essentially written between February and April 1830, though it had been in gestation for well over a year, as shown by stray allusions in Berlioz’s preserved letters of 1829 and early 1830 (CG nos. 113, 126, 149, 151, 152). The completion of the symphony was mentioned by Berlioz in a letter to his friend Humbert Ferrand dated 16 April 1830, in which he declared his intention to leave behind the period of stress he had been going through. This is the first letter to gave a full account of the work and to outline the programme that Berlioz attached to it, and it deserves to be quoted at length (CG no. 158):

[…] I have just clinched my resolve by completing a work which satisfies me completely; here is its subject, which will be set out in a programme and distributed to the audience in the hall on the day of the concert.

Episode in the life of an artist (fantastic symphony on a large scale, in five parts).

PART ONE: a double movement, consisting of a short adagio, immediately followed by a developed allegro (vagueness of feelings, aimless dreams, delirious passion with all its surges of tenderness, jealousy, fury, fears, etc. etc.).

PART TWO: Scene in the countryside (adagio, thoughts of love and hopes troubled by dark forebodings).

PART THREE: A bal (brilliant and stirring music).

PART FOUR: March to the scaffold (fierce and solemn music).

PART FIVE: Dream of a sabbath night.

And now, my friend, this is how I have composed my novel, or rather my history, the hero of which you will have no difficulty in recognising.

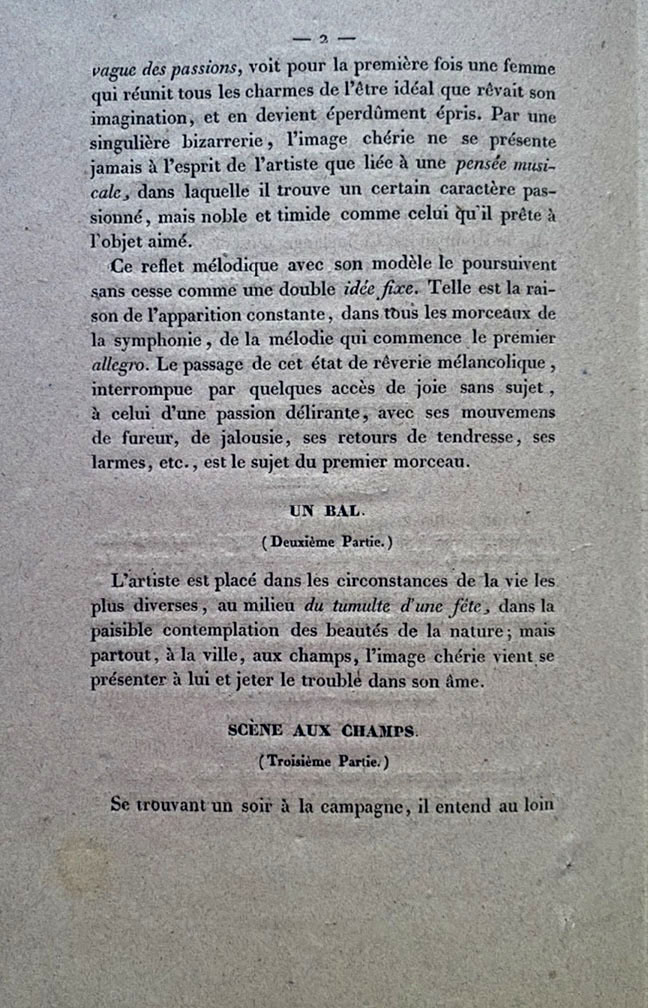

I am imagining that an artist endowed with acute sensitivity finds himself in the state of mind which Chateaubriand has portrayed so well in René, and sees for the first time a woman who realises the ideal of beauty and charm which his heart has been calling for for so long, and falls hopelessly in love with her. By a singular quirk the image of his beloved never comes to his mind without being accompanied by a musical idea in which he finds the grace and nobility which he attributes to the object of his love. This double fixed idea pursues him unceasingly: that is why the main theme of the first allegro (n0 1) constantly returns in every part of the symphony.

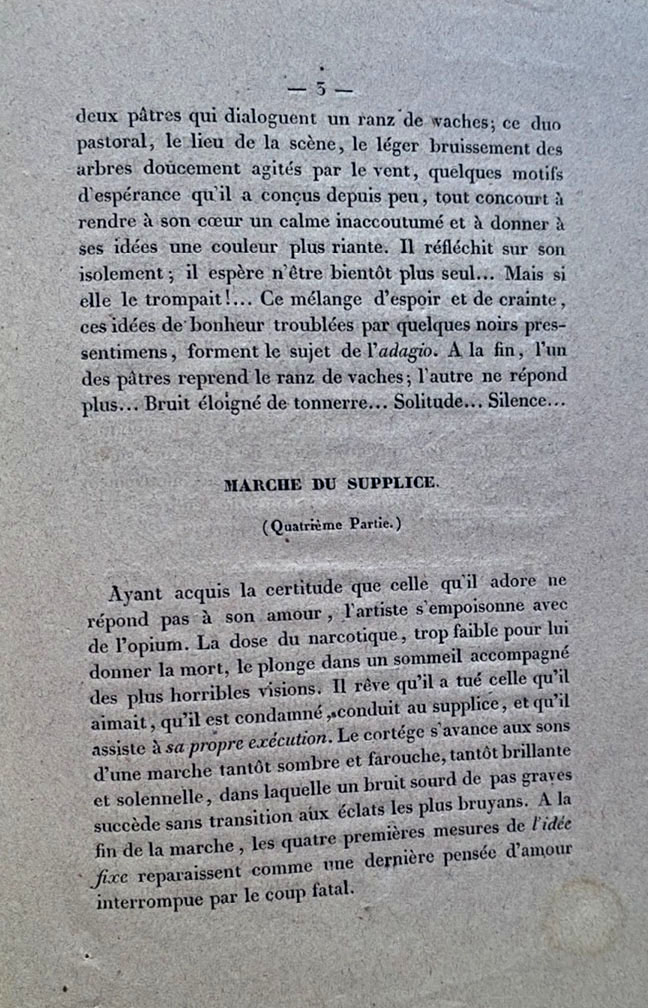

After considerable torment he conceives grounds for hope; he believes he is loved. One day, when he is in the countryside, he hears in the distance two shepherds playing a ranz des vaches between them; this pastoral duet plunges him into a delightful reverie (n0 2). The melody reappears for a moment in the midst of the music of the adagio.

He attends a bal, though the noise of the festivity cannot distract his attention; a fixed idea comes back to disturb him, and the beloved melody stirs his heart during a brilliant waltz (n0 3).

In a fit of despair he poisons himself with opium; but instead of killing him the narcotic gives him a dreadful vision, in the course of which he believes he has killed his beloved, is condemned to death and attends his own execution. March to the scaffold, huge procession of executioners, soldiers and people. At the end the melody reappears again, like a final thought of love, cut short by the fatal blow (n0 4).

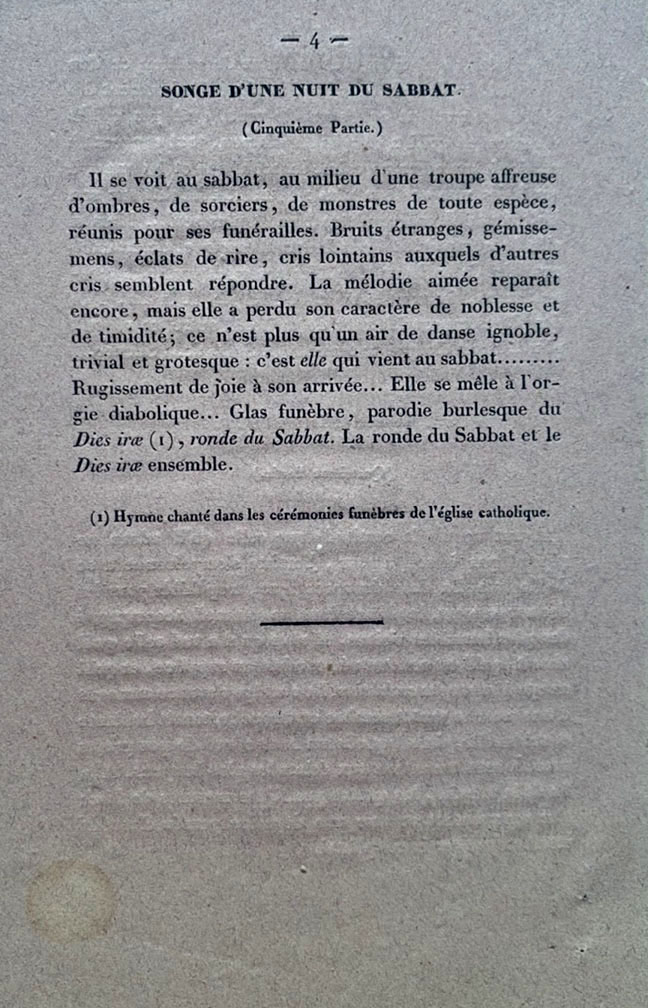

He then sees himself surrounded by a disgusting crowd of sorcerers and devils, gathered together to celebrate the sabbath night. They call from afar. Then the melody arrives, which hitherto only appeared in a graceful form, but which has now become a trivial and ignoble dance tune; it is the beloved now coming to the sabbath, to attend the funeral cortège of her victim. She is now no more than a courtesan worthy of participating in such an orgy. The ceremony then begins. The bells ring, the whole infernal assembly prostrates itself, a chorus intones the plainsong dirge for the dead (Dies irae), two other choruses repeat it in a burlesque parody; then the whirl of the sabbath dance is unleashed and at its most violent climax mingles with the Dies irae, and the vision comes to an end (n0 5). […]

After an abortive attempt to perform the symphony earlier in May 1830 (Mémoires, chapter 26), the work eventually received its first performance at a concert at the Conservatoire on 5 December 1830 (Mémoires, chapter 31), when a copy of the programme was distributed to the audience. The work underwent extensive changes from its earliest version of April 1830. The sequence of the second and third movements was inverted even before the first performance, and the superb Scene in the countryside became the third movement: it forms the centre and pivotal point of the whole symphony, and bridges the transition from the real world of the first three movements to the nightmare of the last two. The second and third movements were also extensively revised by Berlioz during his trip to Italy in 1831-2 (Mémoires, chapters 31 and 34). A piano reduction by Liszt, an enthusiastic admirer of the work, appeared in 1834 (CG nos. 342, 357, 416, 453), but the publication of the full score was delayed for years and only appeared in 1845 (CG no. 915). By this time Berlioz had had many opportunities to test the work in performance, at first in Paris in the 1830s and early 1840s, then abroad as well from 1842 onwards.

As was mentioned at the outset, the programme that Berlioz attached to the symphony may well have done as much to popularise the work as the music itself; it has also helped to establish Berlioz in the minds of many as pre-eminently a composer of ‘programme music’. This is a view of Berlioz which is held even by some of his most devoted admirers, such as the conductor Hamilton Harty (see his 1928 contribution to a symposium on Berlioz). This is not the place to discuss the wider question of whether there is a clear-cut distinction between ‘pure’ or ‘absolute music’ on the one hand, and ‘programme music’ on the other. On this subject the reader may be referred, among others, to Tom Wotton, Hector Berlioz (1935) pp. 83-5, 96-8; Jacques Barzun, Berlioz and the Romantic Century I (1950), pp. 170-98; David Cairns, Berlioz. The Making of an Artist I (1999), pp. 362-9. As far as Berlioz and programme music are concerned, it should be pointed out that the programme of the Symphonie fantastique is in fact unique in Berlioz’s output: this is the only orchestral work to which Berlioz attached a detailed programme, and none of his other symphonic works (his three symphonies and seven overtures), carries any comparable programme beyond a title (for individual movements, in the case of the symphonies).

The programme of the Symphonie fantastique exists in two main published versions, the first of which appeared with the first edition of the work in 1845 (see on this site the original French version which is also available in an English translation). The second version dates from 1855. In February of that year Berlioz performed in Weimar the Symphonie fantastique together with a revised version of its sequel; the original Retour à la vie of 1832 now became Lélio ou le retour à la vie, and Berlioz published it, together with a revised version of the symphony’s programme. The second version of the programme is also available on this site in the original French version as well as in an English translation. There are differences between the two versions of the programme, the most important of which is the greater importance attached in the first version to the importance of the programme for an understanding of the symphony, whereas in the second version the programme is only thought essential when the symphony is performed together with its sequel Lélio. But the music of the symphony remained the same in the 1855 edition as it had been before.

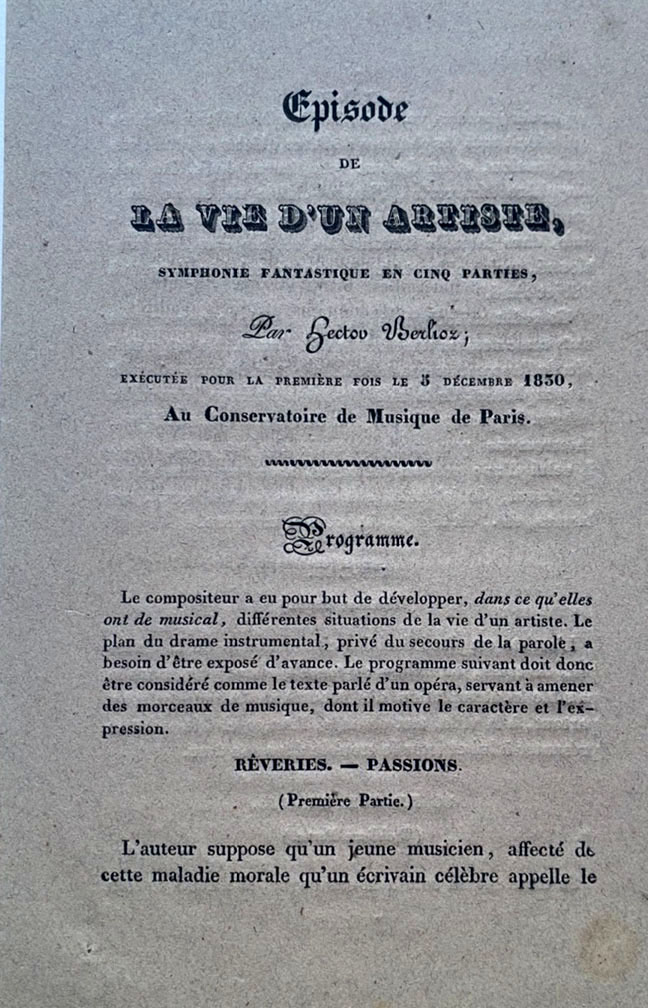

The copy of the programme reproduced below (a 4-page leaflet) comes from a private collection. It will be seen that apart from a few small differences the text is very close to that of the published 1845 version of the programme. The copy illustrated here is reported to have been distributed at the performance on the work on 30 December 1832, the second of two performances at the Conservatoire (the first was on 9 December) when the symphony was played for the first time together with its sequel, Le Retour à la vie, which Berlioz had composed during his stay in Italy in 1831-1832. The earlier performance, on 9 December, was a famous occasion in Paris musical life and also in Berlioz’s own career: Harriet Smithson, who had inspired the symphony, was in the audience and met Berlioz after the concert. The following year they were married. Berlioz gives an account of the occasion in his Mémoires (chapter 44), and his correspondence provides further details (CG nos. 295, 299, 304).

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created on 18 June 1997 by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin; this page created on 8 March 2021.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights reserved.

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Back to page Concerts and performances 1825-1869

Back to page Concerts and performances 1825-1869

![]() Back to page Berlioz in Paris

Back to page Berlioz in Paris