![]()

Introduction

The first visit (1847)

Chronology

Letters of Berlioz

Buildings and venues

The second visit (1867-1868)

Chronology

Letters of Berlioz

Buildings and venues

This page is also available in French

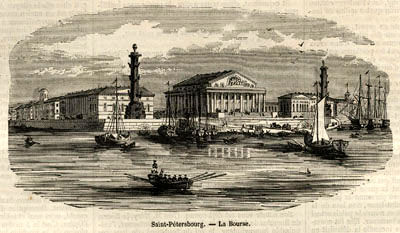

![]()

Berlioz visited Russia twice, in 1847 and again in 1867-1868, on both occasions for about three months in all. Most of this time was spent in St Petersburg, the imperial capital and centre of artistic activity, with briefer excursions to Moscow, and it was there that Berlioz had been invited in the first instance. The evidence available for both visits is also fuller for St Petersburg than for Moscow, notably from the composer’s surviving correspondence, which is extensively quoted in this page (all translations are by Michel Austin); additional material is provided by the account of Berlioz’s trips to Russia published by Octave Fouque in 1882 and by the writings of the critic and champion of Berlioz Vladimir Stasov who witnessed both visits. One important difference between the two visits was the season: on his first trip Berlioz came towards the end of the Russian winter and was able to enjoy benign conditions at the end of his stay, whereas the second trip took place entirely during the winter, which added to the stresses caused by his age and poor health.

Note: the dates below are given in two forms – the first date is according to the Gregorian calendar, in use over the whole of western Europe (France, Germany, Italy etc.), and the second according to the Julian calendar which was still in use in Russia and which was 12 days behind.

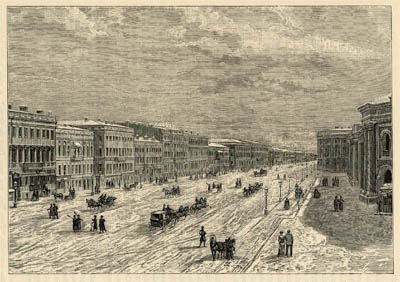

![]()

28 February (16 February): Berlioz arrives in St Petersburg and stays in a

private house on Nevsky

Prospect

14 March (2 March): Prince Odoievsky publishes an article on “Berlioz in St

Petersburg” in the Sankt-Peterburgskie Vedomosti

15 March (3 March): First concert of Berlioz in St Petersburg (at

the Hall of

the Nobility): the

programme included the Fête

chez Capulet from Roméo

et Juliette, the first two parts of La

Damnation de Faust, the Apotheosis of the Symphonie

funèbre et triomphale and the overture Le Carnaval romain.

25 March (13 March): Second concert of Berlioz in St Petersburg (also

at the Hall of

the Nobility), with the same

programme; the

concerts are financially profitable and enable Berlioz to cover his debts

27 March (15 March): Performance of the last movement (Apothéose) of the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale

at a musical festival for the benefit of invalids

31 March (19 March): Berlioz departs for Moscow by sledge; the journey takes

four days

ca 5-20 April (24 March-8 April): Berlioz in Moscow

20 April (8 April): Berlioz returns to St Petersburg

April - early May (April): Idyll

with a young Russian chorister

4 May (22 April): Berlioz meets Princess

Sayn-Wittgenstein for the first time

5 May (23 April): Third concert of Berlioz in St Petersburg: complete

performance of Roméo et Juliette at the Imperial Theatre, together with

the overture Le Carnaval romain and the first two movements of Harold

en Italie

6 May (24 April): Berlioz hears a special performance of mass at the Imperial Chapel

12 May (30 April): Fourth concert of Berlioz in St Petersburg: second complete

performance of Roméo et Juliette at the Imperial Theatre, together with

Part II of La Damnation de Faust

ca 20 May (8 May): Farewell concert by Berlioz in St Petersburg, with the Symphonie

Fantastique and other pieces

The Memoirs provide an account of the long journey from Paris to St Petersburg and of Berlioz’s arrival and stay there (chapters 55 and 56). Few of the composer’s letters survive for the first few weeks of his visit, when he was busy with preparations for his concerts. It was only after the first two concerts, when Berlioz was on the point of departing for Moscow, that he was able to write at length about his experiences, first to his father (CG no. 1100, 31/19 March):

I completed without incident this great trip to St Petersburg which may have worried you. Later to-day I am off to Moscow where I will only stay two weeks, so my sisters can reply to me here. Here is my address: Maison Kosikowski, perspective Newski at the corner of little Morskaïa (St Petersburg).

I have been fortunate to succeed in my musical enterprises beyond all expectations. My music is the rage in all classes of Russian society. The Empress lavished every mark of kindness on me, and her children the Grand-Dukes Alexander and Constantine, and the Duchess of Lichtenberg followed her example. Only the Emperor was unable to attend any of my concerts, as he is ill with a gastro-entiritis which causes him a great deal of worry and pain.

I had an excellent orchestra, composed of German players who performed my music with extraordinary fidelity and verve. For the choral contribution the choristers of the theatre, the imperial chapel, and from several regiments of the guard have been placed under my orders, and they have worked perfectly. The impact produced by my last work in particular has been magnificent, a whole number of pieces have been encored, the Empress called me after the first part of the concert, and she and her sons have congratulated me warmly. Receipts for the two concerts reached a figure which we could not equal in France, and despite the huge expenses I still have about 15,000 francs profit left. Had I arrived two weeks earlier I could have given an additional concert and thus earn an extra 8,000 francs at least, but Lent is over and so too is the concert season. On my return the director of the grand theatre may perhaps be able to suspend work on its repertory and enable me to put on my Romeo and Juliet, which would be a compensation.

The whole Russian aristocracy is showering me with compliments of every kind. They are predicting that my trip to Moscow will be highly successful. Everything here is on a grandiose scale, and neither their customs nor their institutions have anything in common with the ludicrous misconceptions we have in France. The thaw is in full swing, and they hope that the Baltic will be open to navigation in a month and a half; if so I will probably take the opportunity to go either to Copenhagen or to return to France via Hamburg and Prussia. The King of Prussia was kind enough to write to the Empress of Russia about me and I probably owe a great deal to his warm recommendation. […]

The same day he wrote to his friend Auguste Morel (CG no. 1101):

I am leaving for Moscow later today; my two concerts in St Petersburg were highly successful and I regret you were not here to witness this. I had more than 30,000 francs in takings; in the first two acts of Faust (the only ones I was able to perform) two pieces were encored, as was the scherzo of Queen Mab, and I was called back again and again. The orchestra, composed entirely of German players except for one Frenchman, one Englishman and three Russians, was superb and gave me an ovation in front of the public which I will never forget; never in my life have I experienced such intense musical excitement. The chorus did wonders; it was made up of the German singers from the theatre, some of the Court choristers, and singers from four regiments, and I can vouch that from this point of view this performance of Faust left far behind our French choristers. At both concerts we were obliged to repeat in full the Chorus of Sylphs which made far more of an impression than it did in Paris. The Empress summoned me half-way through the first concert and said very kind things to me, as did her sons the Grand-Duke Heir Apparent and Grand-Duke Constantine.

At the second concert and at the musical festival at the Invalides, for which the Grand-Duke had requested a piece, the Grand-Duchess of Lichtenberg and her brothers represented the Court, as the Emperor was rather seriously indisposed. I was also obliged to go to her box to receive her thanks and those of her brother (these were the words used). You can imagine that matters did not stop there. The Empress send me a diamond ring worth 400 roubles (1600 frs.) and the Duchess of Lichtenberg a brooch worth 200 roubles (800 frs.). The entire Russian and German press is on my side both as composer and orchestral conductor; they did not believe the orchestra was capable of such prowess. This will have important consequences later….. I will tell you everything in Paris.

Farewell, my dear Morel, write a few lines on the subject in the musical papers, without forgetting the Gazette musicale which they get here. Brandus besides will be delighted; please show him my letter and give him my regards. Try to see Hetzel; he did me a good service with such unassuming good grace that he has won my affection and I regret not having met him earlier. He is one of those rare people whom one is too happy to come across and whom artists such as ourselves can appreciate better than anyone else. I will write to him in a few weeks [CG no. 1103].

So if the Parisians punished me for writing my last work the Russians have provided ample recompense, and it is to be hoped that Germany will not hold it too much against me for having set to music its great poem. On the way back from Russia I will probably go via Hamburg. […]

Once in Moscow he wrote to the publisher Léon Escudier, with the aim of getting his successes in Russia publicised in the Paris press (CG no. 1102, 5 April/24 March):

Would you like to oblige me with a few lines of advertising in la France musicale? Write them as you please, I find it less silly for me to tell you that in sum my trip to Russia promises to be eminently satisfactory in every respect; my first two concerts in St Petersburg had all the success I could have dreamed of. The Russian aristocracy has seized for Faust with a real delirium tremens, and in two evenings I had takings of 30,000 francs; a great pity that a piano arrangement of the score is not available, as the city is brimming full of pianists and amateur singers, and I could have done excellent business there. However what has been digested is not lost…

The Empress who had not set foot at a concert for years came to my first evening; she asked to see me after the first part of Faust, and I was treated in her box to an ode in prose of compliments on her part and from her sons the Grand-Dukes Alexander and Constantine; then the following day the diamond rings and brooches came to give substance to all these fine words. The mass of the public displayed a furia which I will not call French, for we are very cold compared to these northern dilettanti. The orchestra which had given a superb performance broke into an almighty uproar after the chorus of students and soldiers. In short I brought the house down… it is a good feeling when coming straight from our disgusted and supremely disgusting public of Paris.

At the moment they are rehearsing Roméo et Juliette at the Grand Theatre, and while the choristers are studying their parts I have made a dash to Moscow in four days and four nights to pick this snow-flower, takings of 15,000 francs. It is reported to me as a minimum; we shall see in a few days. […]

Back in St Petersburg he wrote again to Auguste Morel, sending him a detailed press release about his Russian concerts for use in the Paris press, from which the following passage may be excerpted (CG no. 1105, 7 May/25 April):

[…] Berlioz’s appearance among us is a great musical event which will have consequences of the greatest importance for the future of art in Russia. The public has taken him to their heart and the musicians adore him. Yesterday we were attending the dress rehearsal of Der Freischütz which is being staged again for the début of the tenor Franck. As Berlioz was crossing the scene during one piece he was spotted, and the musicians, singers and choristers interrupted the rehearsal and greeted him with applause and endless cries of ‘Bravo!’ We would never have believed that such complex and serious music as his could have made so great and universal an impact in such a short time.

The same day he sent a detailed and more personal report of the latter part of his Russian trip to his sister Adèle (CG no. 1106):

[…] On my return from Moscow, where I also did excellent business, I have just put on a performance of Roméo et Juliette at the Grand Theatre; the house was full and such was the success that we are going to repeat the same work next Wednesday. But it will be my farewell concert, the sun has become so beautiful and warm that soon people will be off to the countryside, which they are more than entitled to after this interminable winter. The public and the musicians are all on my side, and everyone lavishes on me marks of kindness and affection. Yesterday the Grand Duchess most graciously ordered a performance of mass in her chapel for my own private benefit, to let me see and hear her wonderful court singers performing their religious function – they leave far behind those poor wretches of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. I am still in a state of great agitation and trembling from the indescribable emotion I experienced. These are truly celestial choruses, and infinity opens up before anyone who hears their strange and sublime harmony. I would not advise anyone gifted with any degree of sensitivity and acquainted with deep grief to expose himself to such an experience; it is enough to break your heart and tear out your soul. And what majesty in this Greek ritual, what simple and solemn pomp…… it is immensely beautiful. They would like to make me stay here, everyone even says that this is what they will. The fact is that the idea was mentioned to me in high places, and there are many people who are busy making arrangements. But it is a far-reaching plan: it would involve giving me a general superintendence of music in Russia, covering theatres, churches, military music, the Conservatoire, everything in short. There are innumerable positions that cannot be abruptly terminated, someone to pension off here, someone else to remove there, etc., etc. The emperor alone could do everything with one word, but he says his budget for music is rather depleted at the moment. His sons have little power and dare not speak out loud. I hope that matters will eventually be sorted out in my absence. The Empress is full of graciousness and goodwill for me, as are all those around her; it is believed that she might come again to my last concert. […]

My god, how sad I am! I am in the midst of one of my nervous crises, thanks to the performance of Roméo, to the Greek mass, and to spring. It hit me during the concert, the day before yesterday, in the scene in the gardens of Capulet; then during the oath of reconciliation, when the chorus launched into the crowning piece of my musical fireworks, instead of the joy I should have felt at the climax of my work, all I experienced was a dreadful pang of anguish, and I anxiously followed every bar of my score as the end approached and I was brought back to silence and to the darkness of night. The public called me back I do not know how many times, and I had to go to the front of the stage and bow with an air of contentment when I would have liked to lie down behind the scene and weep to my heart’s content…… So I had to come to Russia to hear my favourite work performed in grand style, while it has always been more or less roughed up everywhere else. But I was also in good form the day before yesterday, suffering as one needs to be to catch the spirit of the work. And how well I conducted, how well I played the orchestra! Only the author can know how well he has been served by the conductor! It is such a difficult task for this score!… one lapse of concentration and you are lost, a touch of coldness and the music becomes flat, the nightingale turns into a blackbird, orange blossom has the fragrance of elder, and Romeo turns into a student… […]

Two days later a letter to Liszt, who had been in St Petersburg only weeks before Berlioz’s arrival, gives the first mention in the composer’s correspondence of Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein who was later to play a decisive part in persuading Berlioz to compose Les Troyens (CG no. 1108, 9 May/27 April):

A charming and witty princess, who knows better than we do where you are heading and what you are doing, had kindly agreed to take care of this letter and make sure it reaches you. Greetings, dear and wonderful pilgrim! I think a great deal of you, and the opportunities of talking about you are frequent here where everyone loves and admires you almost as much as I admire and love you. Do you not think that the two of us wander about a great deal!…

At this moment I am sad, sad to the point of death. I have been seized with one of my fits of isolation; it is the performance of Roméo at the Imperial Theatre which provoked it. In the middle of the adagio I felt my heart tightening; that’s it, and heaven knows how long it is going to grip me.

What a deplorable temperament I have!…

But enough of this; I have been playing a great deal of music here, I am giving my fourth and last concert next Wednesday, again with the complete Roméo et Juliette and part of Faust. There is also the concert at court; I have been asked to take part in it, and it is on the same day. The Empress and the princes are very charming with me. My music has caught on immediately, I made a lot of money, was given presents and all the rest. […]

Berlioz left Saint-Petersburg on 22 May, stopping on the way at Riga (at the time part of Russia) and Berlin to give concerts, before he was eventually back in Paris towards the end of June.

![]()

Unless otherwise stated all pictures throughout this page have been scanned from engravings, photos, postcards and other publications in our own collection. All rights of reproduction reserved.

We are most grateful to Pepijn van Doesburg for information on the history of the buildings connected with Berlioz’s visits to St Petersburg and for the 2003 photos on this page for which he holds the copyright.

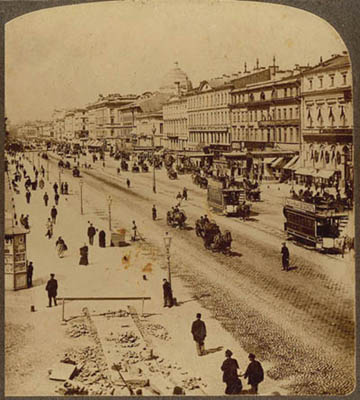

On his 1847 visit to St Petersburg Berlioz was lodged in a private house on Nevsky Prospect. His address, as given in a letter to his father Dr Berlioz, was “Maison Kosikowski, perspective Newski au coin de la petite Morskoïa (Pétersbourg)” (CG no. 1100).

We do not know if Maison Kosikowski was the building at the east or the west corner of Nevsky Prospect and Malaya Morskaya streets. The one at the east corner seems to date from the mid-19th century, so it could perhaps be the one Berlioz stayed in; the one at the west corner is the Wawelburg building, which was built perhaps as a bank somewhere around 1900; architect: Peretyatkovich.

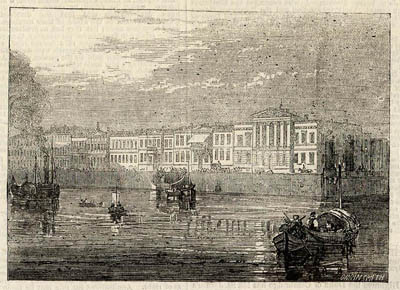

Berlioz gave two concerts in 1847 and six concerts in 1867/68 in the Hall of the Nobility, which is still extant. It was built from 1834 to 1839 by P. Jaquau, and occasionally served as a concert hall until it became the seat of the Philharmonic Society in 1921. Since then the St. Petersburg Philharmonic performs there, and it is known as the Bolshoi zal (big hall) of the Filarmonia imeni Shostakovicha (Shostakovich Philharmonia). The upper storey was added at a later stage. The interior also seems to date from a later period.

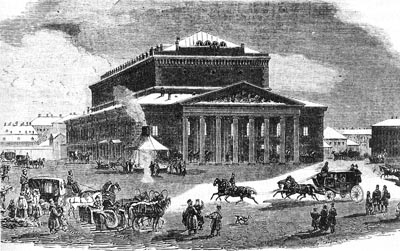

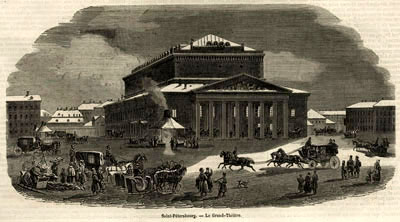

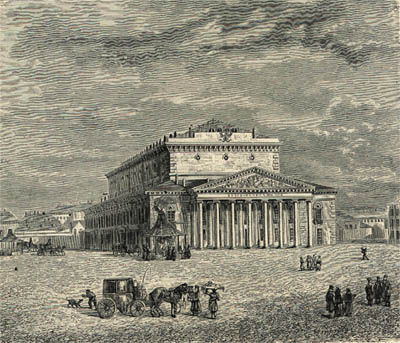

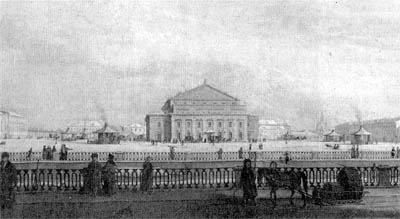

Berlioz gave two of his 1847 concerts in the Imperial Theatre, referred to as the ‘Grand Théâtre’ in his correspondence. The Theatre stood on the site where the Rimsky Korsakov Conservatoire now stands. It was first built in 1775-83 by A. Rinaldi and rebuilt in 1802 and 1835 by architects Z.-F. Toma de Tomon and A. K. Kavos respectively.

The Conservatoire building dates from 1881 to 1896 and was designed by Vladimir V. Nicolas.

Berlioz attended a performance of a mass by Bortniansky here during his first visit to Saint-Petersburg.

The origins of Glinka Capella date back to the latter part of the 15th century, to a particular group of performers who traditionally chanted orthodox liturgy solo and in ensemble, unaccompanied by any instruments, known variously as the Tsar’s Singing Clerics, the Court Singers, the Imperial Court Chapel, and the Glinka State Capella. In the 19th century for a brief period Glinka was the choral director of the Imperial Chapel. He was appointed to this post shortly after the triumphant première of his opera A Life for the Tsar in St Petersburg in December 1836. But three years later, following a marital crisis and separation from his wife in l839 Glinka also resigned from the Imperial Chapel.

The Glinka Capella of today is a building dating from 1887/89 designed by Leonti Benois, but it stands at the same place as the building where Berlioz went to hear Bortniansky’s mass.

![]()

17 November (5 November): Berlioz arrives at St Petersburg, and stays at the

Mikhailovski Palace

24 November (12 November): Berlioz holds a dinner party at the Mikhailovski

Palace for a select gathering of Russian musicians; Stasov,

Balakirev

and Cui are

invited, but not Borodin, Mussorgsky or Rimsky-Korsakov

26 November (14 November): Berlioz writes to Damcke in Paris asking him to send

a copy of the full score of Les Troyens

28 November (16 November): First concert in St Petersburg: Beethoven, Pastoral

Symphony; Mozart, Chorus of priests from the Magic Flute; Berlioz,

overture Benvenuto Cellini; Mozart, Susanna’s aria from the Marriage

of Figaro (Mlle Regan); Mozart, Ave Verum; Berlioz, Absence

(Mlle Regan); Weber, overture Oberon

7 December (25 November): Second concert in St Petersburg: Beethoven, overture Leonora

[no. 2]; Gluck, excerpts from Iphigenia in Tauris; Berlioz, Symphonie

Fantastique

11 December (29 November): Celebration for Berlioz’s birthday in St Petersburg;

he is made Honorary Member of the Russian Musical Society

14 December (2 December): Third

concert in St Petersburg: Berlioz, overture Carnaval romain;

Wieniawski,

Violin concerto no. 1 (H. Wieniawski); Gluck, Orphée Act II; Berlioz, Rêverie

et caprice for violin and orchestra (H. Wieniawski); Beethoven, Symphony no.

5

28 December (16 December): Fourth

concert in St Petersburg: Beethoven, Symphony no. 3 Eroica; Berlioz, Offertorium

from the Requiem; Gluck, excerpts from Alceste; Berlioz, overture Les

Francs-Juges

1 January (20 December 1867): Berlioz

leaves St Petersburg for Moscow

13 January (1 January 1868): Berlioz

leaves Moscow for St Petersburg

25 January (13 January): Fifth concert in St Petersburg: Weber, overture Der

Freischütz; Paganini, Violin concerto no. 1 (Wilhelmj); Weber, Agathe’s

aria from Der Freischütz (Mlle Regan); Beethoven, Piano concerto no. 5

(Josef Derffel); Bach, Aria for violin with string accompaniment (Wilhelmj);

Haydn, Aria from The Creation (Mlle Regan); Beethoven, Symphony no. 4

5 February (24 January): Berlioz

goes to a performance of Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar but leaves during

the 2nd Act

8 February (27 January): Sixth and last concert in St Petersburg: Berlioz:

excerpts from Roméo et Juliette; excerpts from La Damnation de Faust;

Symphony Harold en Italie (Weickmann, solo viola)

13 February (1 February): Berlioz leaves St Petersburg

By the time of his second trip to Russia Berlioz had completed the writing of his Memoirs, which terminate in 1865, but the composer’s correspondence for this period is comparatively full, more so than for the trip of 1847. The tone of the letters is markedly different from those of twenty years earlier: apart from his poor health and the stresses caused by the harsh Russian winter, Berlioz had no further interest in publicising his successes in the Paris press (compare CG nos. 1101, 1102, 1105 for the earlier trip). He wrote very detailed accounts of his experiences in St Petersburg (and also Moscow), but only for a small circle of relatives and close friends. That circle had itself changed since the earlier visit. Within his family only his uncle survived of the older generation (CG no. 3310) and both of his sisters were now dead, but their children, his nieces, remained very close to him (CG nos. 3305, 3319, 3327). Among his close friends relations with Princess Sayn-Wittgenstein had in practice come to an end shortly before he left for Russia (cf. CG no. 3296) and it was only after his return that he sent a brief account of his trip to Auguste Morel (CG no. 3360). Although he had informed Humbert Ferrand of his projected trip (CG no. 3286, cf. 3292), it does not appear that he wrote to him again after his departure. His closest friends included now Berthold and Louise Damcke (CG nos. 3308, 3326), the pianist Mme Massart and her husband (CG nos. 3318, 3330), the singer Mme Charton-Demeur and her husband (CG no. 3335), the instrument maker Édouard Alexandre (CG no. 3315; he was one of Berlioz’s testamentary executors), the composer and critic Ernest Reyer (CG no. 3332), and, to Berlioz the most important person of all, Estelle Fornier (CG no. 3330), whom he had seen again in Lyon in 1864 after more than 30 years and with whom he was now in regular correspondence (CG nos. 3314, 3331).

Unlike the earlier trip, the detailed coverage of Berlioz’s stay in St Petersburg in 1867 starts almost from the time of his arrival, with a letter to his niece Nancy Suat (CG no. 3305, 18/6 November):

I arrived yesterday in far better shape than I left Paris. The Grand-Duchess is wonderfully kind; she had me met at the railway station and immediately I was taken away in a good carriage and driven to Mikhailovski Palace where a superb apartment awaited me. I have immediately had several visits, and in spite of my less than graceful appearance (four nights in a train leave you in poor shape) I had to entertain all these people.

Starting already tomorrow I will have to busy myself with the preparations for the first concert, which will take place on the 28th of this month. I will have a lot of trouble with the singers and choristers, and they say that only the orchestra is above reproach. Anyway, I will do my best to make use of all these resources. I have not yet seen my gracious hostess; she has just let me know that she will receive me at 3 o’clock, so I need to get dressed and put on a white tie, which is not the best part of the job. This evening I expect my vast sitting room to be full of people. It is snowing heavily; it is already a foot deep in front of my windows. It goes without saying that I am not venturing outside. I have servants who speak French and have nothing to worry about. But I have just heard that the rehearsals at the Conservatoire will be at 9 in the morning, which is a problem – I find it so difficult to get up.

Heavens, what snow! I can see swarms of sparrows and pigeons looking for grains of barley dropped by horses in the snow, without fear of seeing their legs freeze. People ride by in sledges with their heads covered by heavy hoods. And this vast square, this frozen silence. In a few days all these impressions will disappear, I will be steeped in music and will not be thinking of anything else. I really had to leave Paris to come back to life! […]

WHAT SNOW!!!

To Berthold Damcke (CG no. 3308, 26/14 November):

[…] Yesterday [in fact on the 24th] there was a gathering in my apartment of a dozen or so of the leading Russian musicians and critics, and they reproached me so much for not having brought any of the music of Les Troyens and were so insistent that in the end I gave in. Their idea is to have large excerpts from this work performed after the sixth concert of the Conservatoire. They all know the piano score. Please therefore go to my flat (my mother-in-law has been warned) and among the manuscript scores that are locked in the wardrobe with a mirror in my bedroom take the copy made by Roquemont of the complete full score of Les Troyens. Then take the separate parts of the same work which are on my piano (but not the choral parts) and have everything, score and parts, packaged in a box with the following address: To Monsieur Hector Berlioz, c/o Madame the Grand-Duchess Yelena of Russia, Mikhailovski Palace, Mikhailovski Square (St Petersburg). Please make sure that the box is robust and that it is properly packaged for rail transport. You will tell my mother-in-law how much all this will have cost and she will refund you. I am very anxious to hear from you that it will reach me safely. I am in the midst of the rehearsals for my first concert which takes place next Saturday. The chorus is large, but they are amateurs who rehearse more or less when they feel like it, so you can imagine… The orchestra is superb, first rate. I will not tell you anything about all the flurry around me, I am entertained and welcomed everywhere as well as can be.

The cold and the snow are dreadful. […]

Do not mention to anyone my request about Les Troyens.

Take also in the wardrobe with a mirror a libretto of Les Troyens which must be there, and send it with the music.

To his uncle Nicolas Marmion (CG no. 3310, 8 December/28 November):

I am writing to you this evening because I feel a little better and because I want to comply with your request; you asked me to write to you after my second concert. I am caught here in a musical whirlwind which I could hardly describe to you. The public, the artists, the press, the Grand-Duchess, Prince Constantine, everybody congratulates and praises me and gives me the most gratifying support. The second concert took place yesterday in the great Hall of the Nobility (where I gave my first concert twenty years ago [15 March 1847]). My entrance was greeted, like the start of the concert, with interminable applause; I did not know how to react, and after taking bows to the right, the left, in front, behind, to the orchestra and the chorus, I had to stand still and wait for this eruption of enthusiasm to come to an end. I have been forced to change my second programme and to introduce in spite of its huge difficulties my Symphonie fantastique. This vast work achieved a dazzling success, all the movements were greeted with applause and the March to the scaffold was encored. Let me say that the orchestra was superb; I had asked for three rehearsals; as a result the performance was flawless. You had to see this audience after the symphony! I was recalled more than six times; some fanatical enthusiasts were embracing me furiously, others kissed my hand, the orchestra made a terrific noise by hitting their violins and basses with their bows and I who had not heard this symphony for more than ten years [on 22 February 1855 in Weimar] was struggling to contain myself and not yield to the temptation which the Scene in the fields had aroused of bursting into tears. « What! some critics were saying to me, you wrote this work 40 years ago! We are thoroughly ashamed not to have known it earlier. But fortunately we know many of your other works. » One newspaper has expressed thanks to the Grand-Duchess for the imperial present, as it puts it, that she made to St Petersburg by hiring me for this season.

Her Highness lavishes every kind of attention on me. I do not know how long I will be staying here; the concerts cannot take place regularly every week and there is already talk of my going to Moscow. But I will not yield and after the 6th concert I will go back to Paris. I am constantly ill here, the combination of dreadful frost followed by a thaw hurts me terribly. I see many Russians whom I welcome from my bed without any ceremony. Only music revives me a little. At the first concert I conducted a performance of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony and I was lost in adoration for this poor great man who was capable of creating such an astonishing piece of musical poetry. And how we sung that poetry! What a fine orchestra! These excellent musicians do whatever I ask of them. […]

To Estelle Fornier (CG no. 3314, 14/2 December):

Do not be cross with me if I write to you, I am not asking for a reply; but I think I should tell you a little about my life in this great capital of snow and ice. I am conducting tomorrow my third concert; the public and the musicians overwhelm me with demonstrations of affection and enthusiasm: every time I appear there is such applause that I do not know how to respond. My task involves conducting a wonderful orchestra which is entirely devoted to me and with which I can do anything I like. […]

Tomorrow there are only two pieces of mine in the programme, the overture Carnaval romain and the romance Rêverie et caprice for violin. The bulk of the programme consists of Gluck’s Orphée which at this morning’s rehearsal stirred me to the depths. For this masterpiece Mme the Grand-Duchess wanted me to have a very large chorus, and I have an imposing body of 130 singers. Her Imperial Highness overwhelms me with kindness; the day before yesterday she sent me an album with a malachite cover; I could not see why – it is because it was my birthday, and she had somehow found out. In the evening the musicians put on a dinner for 150 guests in my honour. I leave you to imagine all the toasts; there were many men of letters there. All these gentlemen speak French. Grand-Duchess Yelena asked me recently to come and read her Hamlet one evening. She knows her Shakespeare well enough to inspire the reader with confidence. The poor lady owns property which brings her 8 million roubles in rent (32 million francs); she does immense good to the poor and to artists. And yet I am often bored in the beautiful apartment she has given me and I am unable to accept all her invitations. I spend much of my time in bed, especially after the rehearsals and the concerts which exhaust me. She has your queenly bearing and gait, but that is part of her status. When will I be able to see you? There are days, especially in the mornings which I feel the greatest pain, when it seems it will be never… and then music revives me and my strength returns when I conduct masterpieces. […]

To Édouard Alexandre (CG no. 3315, 15/3 December):

[…] What an orchestra! what precision! what ensemble! I do not know whether Beethoven ever heard his music performed in this way. So I must tell you that, in spite of my pain, when I come to the podium and I see myself surrounded by all this good-will I feel revived and I conduct as perhaps I never have before.

Yesterday we were to perform the second act of Orphée, the symphony in C minor and my overture Carnaval Romain. All this was played in a sublime way. The young person who is singing Orphée (in Russian) has an incomparable voice and acquitted herself very well of her part. There were 130 choristers. All these pieces scored a wonderful success. And these Russians, who only know Gluck through horrible mutilations made here and there by incompetent people!!! For me it is immense joy to reveal to them the masterpieces of this great man. Yesterday the applause went on endlessly. In two weeks we will be giving the first act of Alceste. The Grand-Duchess has given instructions that I should be obeyed in everything; I do not exploit her order, but I make use of it. […]

Here they love what is beautiful, here life is dedicated to music and literature, here they have a fire in their heart which banishes thoughts of snow and ice. Why am I so old, so exhausted? […]

To Mme Massart (CG no. 3318, 22/10 December):

[…] [At the 5th concert] I will give the first three instrumental movements of Beethoven’s Choral Symphony. I dare not risk the vocal finale, as the singers available to me here do not inspire enough confidence… [the performance of the 9th symphony was altogether cancelled] […] At this point I am being interrupted in my sitting-room where I am alone as I write this, because Mme the Grand-Duchess is giving this evening a musical party where she would like to hear my duet from Béatrice et Bénédict; the accompanist and the two singers know the piece to perfection (in French). So I have just sent to Her Highness the score, with instructions to the three virtuosi to have no fear, because they all know the music thoroughly. As for me I am going back to bed. […]

To his niece Joséphine Chapot (CG no. 3319, 28/16 December):

[…] My last rehearsal took place yesterday morning, and there are few examples of a comparable impression produced by the Offertorium of my Requiem. I was exhausted, and this revived me.

In a few hours I will have to conduct also the temple scene from Alceste; I had great difficulty in getting it to work, but now it is going well. What a joy to introduce a people to works of such beauty! the Russians do not know Gluck! but they know Verdi and so many others……

I have just been asked for a seventh concert on my return from Moscow. I did not want to commit myself. I long for my bed in rue de Calais; I long to go and see you, my dear nieces, on my way to Nice and Monaco. I am so worn out!

Yesterday after the Offertorium of my Requiem a music-lover asked me: « What did the Parisians say after a piece like this? — They did not pay attention. — They did not pay attention! » and the man turned away and started to wipe his tears. They are going to perform the Requiem complete with 800 performers once I am back in the killjoy country that is France. They will rehearse the chorus for two months. […]

After his return from Moscow he writes to Mme Massart (CG no. 3330, 18/6 January):

I am back from Moscow and on entering my sitting-room I find a small pile of letters, among which yours [CG no. 3325] does not cause me the greatest joy, because there is also another one I was not hoping for, you can guess from whom [i.e. Estelle Fornier]. Yours nevertheless caused me great pleasure. It should have left me indifferent, but there you are, no one is perfect. All the same I read your very cordial words and I am replying today. […]

The programme for my concert next Saturday [25 January] is fixed. I have nothing to do with it, which is just as well, as the next and last concert is made up entirely of my own music. What joy it will be when I will have beaten the last bar of the finale of Harold! when I can say to myself: ‘I am leaving for Paris in three days, that is at the beginning of February.’ I cannot put up with this climate. I suffered less in Moscow. And what enthusiasm they all showed! […]

What are you talking about, telling me to give you a concert in Paris? Were I to give a concert to my friends, spending a mere three thousand francs, the press would insult me all the more.

After seeing you in Paris I will go to Saint-Symphorien [where Madame Fornier lived at the time with one of her sons and his family] and from there to Monaco to lie amid the violets and sleep in the sun. I suffer so much, my pain is so ceaseless, that I don’t know what to do with myself. I don’t want to die now, I have enough to live. […]

To Estelle Fornier (CG no. 3331, 23/11 January):

[…] Next Saturday we are giving here my fifth concert, and two weeks later my sixth. After that, whatever the cold, I will leave for France, for the sun, for Saint-Symphorien, for life. If you knew how long my days feel in my vast sitting-room, what tedious arguments with the singers over the organisation of the programmes, what intolerable conceit I find again here, from which I had long been free in Paris.

This adds to the hideous fatigue caused by these concerts. I have already refused all those I was being offered after the six for which the Grand-Duchess made me sign a contract. I refuse dinners, I refuse to go out in the evenings; I am unwell all the time. All I ask for is to have enough strength in three weeks’ time to travel four days and four nights in the snow. […]

Today was the great festival of the blessing of the Waters of the Neva; the Emperor was present, there were 600 priests, and the entire city was running on the ice. They say it is a fine sight. I did not leave my fireplace. The Emperor comes every two or three days to see my hostess the Grand-Duchess; I have not seen him yet. […]

To Ernest Reyer (CG no. 3332, 23/11 January):

[…] Here as in Moscow I am showered with attention, with repeated invitations, parties and dinners. And I barely have the strength to hold out against all this, so ill am I all the time. Fortunately I have only two concerts left: the concert I am conducting tomorrow but where I do not figure as composer, and the following one in 16 days where on the contrary the whole programme is made up of my music. It will include excerpts from Roméo et Juliette, from Faust, and the complete Harold symphony. I will be very tired, and will need four rehearsals. What a fine orchestra I have! They understand quickly and well. And they know almost the whole of my music. As for Beethoven, they play him almost by heart. This morning I was deeply moved by the symphony in B flat [no. 4] which we played without stopping once. Music would have cured me in this trip, had it been possible for me to recover my health. But alas! I am more and more ill, and there are days when I remain half-dead at the rehearsals. What news from you? I do not read anything, I do not know anything; I am in an immense apartment which the Grand-Duchess has given to me, and where I am often bored to death. Sometimes there are friends who come to see me, who have for my music a passion which looks very much like fanaticism. You must hear them talk…… The Conservatoire has purchased a manuscript copy of the full score of Les Troyens; they are going to translate this work into Russian and stage it once they have been able to train a rather large number of singers. They are short of them at the moment. It has never been possible to organise a performance of the Septet. They were asking me to perform at the next concert the descriptive piece for orchestra (‘the hunt in the forest’ [the Royal Hunt and Storm]) and the ballet pieces; but I was the one who refused. This work should not be broken up into fragments like this and made to look like an instrumental work. […]

To the English violinist and composer Alfred Holmes, who had asked about the possibility of coming to St Petersburg to give concerts (CG no. 3334, 1 February/21 January):

[…] Despite all the offers to stay on that I receive, I want to leave; cold and snow are driving me away, and my health cannot withstand these temperatures. I have a rehearsal this evening and I shudder in advance. […]

At the moment we need to make a success of a very demanding programme which the Grand-Duchess approved for my final concert. The concert they wanted me to give for myself in March would have detained me here for over a month; I would rather sacrifice 8,000 francs and return immediately.

All the kindness displayed by everybody, the musicians, the public, all the dinners and presents, make no difference. I want the sun, I want to go to Nice, to Monaco. […]

Six days ago there were 32 degrees of frost. Birds were dropping dead; cab-drivers were falling off their seat. What a country! And to think that in my symphonies I sing of Italy, of the sylphs and rose-bushes by the banks of the Elbe!!!… […]

The last preserved letter of Berlioz from Russia is addressed to Jules-Antoine Demeur (CG no. 3335, 7 February/27 January):

[…] It is six o’clock and I have just got up. This morning we had one final rehearsal for the last concert, which exhausted me. The adagio from Roméo et Juliette upset me very deeply, I would have liked to weep all the tears in my body; the scherzo of Queen Mab went without a single mistake, and so too the scene from Faust and Harold and everything, but at the end I was finished, though delighted to see this orchestra so proud of itself. I made my farewell to everyone, the choristers and the orchestral players; the concert is tomorrow evening; we will have a huge crowd. I will tell you in Paris about my trip to Moscow, and the acts of kindness of the musicians towards me, and those of the Grand-Duchess. But I am in such pain that all this is almost indifferent to me. […]

The evening tomorrow will probably be splendid, and I need to bear that in mind to forget my pain. How pleased I would be to have you here!

I have not seen your friend the flautist, he is not in my orchestra, but I have another flautist of exceptional talent. Many people come to the rehearsals, which I cannot prevent. What violins! what wind players! how quick they are to understand!

Two days ago I went to the Russian opera to see A Life for the Tsar by Glinka; the theatre’s singers are miserable, the chorus dreadful, the orchestra very good, and Glinka’s work is very original; the conductor is generally agreed to be an oyster. […]

As Berlioz repeatedly stated to his correspondents, he had no intention of prolonging his stay in Russia beyond what his contract stipulated, and wanted to return straight to Paris (a possible stop at Cologne that he had suggested to Ferdinand Hiller before leaving [CG no. 3281] was not even considered). He left St Petersburg by train on 13 February and arrived in Paris four days later.

![]()

Berlioz stayed here during his second visit to St Petersburg in 1867/68. The palace was built from 1819 to 1825 by Carlo Rossi, and now houses the Russian Museum. Berlioz’s apartment had a view on the square and the Hall of the Nobility opposite.

The snow-covered ground in this 20th century postcard is probably not much different from the ‘vast square’ and its ‘frozen silence’ that Berlioz saw from his window (CG no. 3305).

The Mariinsky Theatre, known during the Soviet Union era as the Kirov Opera and Ballet Theatre, reverted to its original name in 1992. The present building, which dates back to 1857, originally housed another theatre (“Opéra Russe”) but was remodeled and taken over by the Mariinsky company. During pre-revolutionary times the theatre enjoyed royal patronage and has played host to some of Russia’s most celebrated classical performers.

Berlioz attended a performance of Glinka’s first opera A Life for the Tsar at the Mariinsky Theatre on 5 February 1868. He was seated in Kologrivov’s loge with Balakirev and Stasov (Stasov p. 166). He had seen this opera 20 year earlier at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre during his first visit to Russia in 1847.

According to Rimsky-Korsakov Berlioz left before the end of the second act. Stasov recalls the occasion (Stasov, p. 166):

We heard none of the fresh, profound remarks we expected from one who had been so enthusiastic about this opera twenty-two years before. By now it was too much of a strain for Berlioz to sit in a theatre an entire evening (he was accustomed to retiring at nine o’clock). He praised Glinka’s opera as a whole but made only one specific comment, concerning the orchestration: “How pleasant it is to come upon such restrained, beautiful, sensible orchestration after all the excesses of today’s orchestras!”

![]()

Related pages on this site:

Berlioz in Moscow

Octave Fouque: Berlioz en

Russie (in French)

Berlioz and

Russia: Friends and Acquaintances

The

Russia that Berlioz visited, by Dr Linda Edmondson

Hector

Berlioz as reflected in the Russian press of his time, by Dr Elena Dolenko

![]()

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for the text and all the photos, engravings and information on Berlioz in Russia pages. All rights reserved.

© 2003 Pepijn van Doesburg for 2003 photos. All rights reserved.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.