Le Chuzeau

This page is also available in French

![]()

The Berlioz family was settled in La Côte for many generations before the birth of the composer, and owned there numerous farms and lands. The Livre de raison kept by Dr Berlioz, the composer’s father, between 1815 and 1838 provides a wealth of information on these family estates, the management of which Dr Berlioz supervised with loving care (see David Cairns, Berlioz vol. 1 [London, 1999], pp. 3-5). Berlioz’s musical career in Paris and across Europe inevitably took him away from his birthplace and the family estates, which he only mentions rarely in his writings and letters.

One of these estates, the farm called Le Chuzeau just outside La Côte, was connected with a dramatic episode in the composer’s life which he narrates in his Memoirs (chapter 10, cited below).

Located just outside La Côte Saint-André, the farm of Le Chuzeau was a favourite haunt of the Berlioz family; it was part of a large domain which the grandfather of the composer had acquired at the end of the XVIIIth century. The farmstead consisted of an imposing group of buildings arranged around a long inner courtyard. The farm remains in the same condition as in Berlioz’s time. Today, the owners of the farm are the descendants of the same farmers who worked on it when it belonged to the Berlioz family (Antoine Troncy, ‘Le Chuzeau’, in Hector Berlioz. Episodes de la vie d’un artiste, published by the Musée Hector-Berlioz, under the direction of Chantal Spillemaecker, Grenoble, 2003, p. 26). The farm buildings, including its pavilion, were sold by the Berlioz family in 1865.

The pavilion nicknamed by popular tradition “pavilion of the curse” [pavillon “de la malédiction”] in memory of the famous scene told by Berlioz dates actually from after the event itself – it was built only in 1827. Moreover Berlioz himself does not refer to the pavilion in his account, only to the farm as a whole, and the main argument with his mother took place according to him at the family home and not at Le Chuzeau.

The exact date of the episode related in the Memoirs is not established, but belongs to the period of tension between Berlioz and his family, after his arrival in Paris in late 1821 and his decision to give up medicine to become a composer. The incident took place during one of the visits he made to La Côte between 1823 and 1825 to put his case against the opposition of his family. According to David Cairns (Berlioz, vol. 1, pp. 119-22, 181-3) it should be dated to 1823, and it is probably the case that Berlioz in his Memoirs conflated several different visits to La Côte into one single episode. Berlioz’s own account runs as follows:

To understand what follows, you have to know that my mother, who had very strong religious convictions, was also very firm in her views about the arts and everything that relates more or less closely to the theatre — views unfortunately shared even nowadays by many people in France. For her actors and actresses, singers, musicians, poets and composers were all monstrous creatures, excommunicated by the church and as such doomed to hell. […]

My mother was thus convinced that if I turned to musical composition (which, according to French ideas, does not exist outside the theatre), I was stepping on a path that would lead to disrepute in this world and perdition in the next. The moment she heard what was afoot her soul stirred with indignation. The look of anger on her face warned me that she knew everything. I thought it prudent to stay out of sight and keep a low profile until the moment of departure. But I had hardly taken refuge in my room for a few minutes when she followed me there, her eyes ablaze, with all her gestures betraying extraordinary agitation:

« Your father, she said, abandoning her usual way of calling me tu, has had the weakness of agreeing to your return to Paris, he is abetting your extravagant and sinful plans! I will not have the same reproach to make to myself, and I am categorically opposed to this departure!

— Mother!…

— Yes, I am opposed to it, and I implore you, Hector, do not persist in your madness. See, I fall on bended knee, I, your mother, and I humbly beseech you to give up the idea…

— Mother, for God’s sake, allow me to raise you, I cannot … bear this sight…

— No, I will not move!… » Then, after a moment’s silence: « You are spurning me, you wretch! The sight of your mother at your feet leaves you unmoved! Then be gone! Go and drag yourself in the filth of Paris, disgrace your name, suffer your father and I to die of shame and sorrow! I am leaving the house until you get out. You are no longer my son! I curse you! »

Is it conceivable that a mixture of religious fervour and provincial bigotry, with its insolent disdain for the cult of the arts, could have brought about a scene like this between a mother as tender as mine and a son as grateful and respectful as I had always been?… I can never forget the preposterous, unbelievable, horrible violence of this scene. It did much to foster in me the hatred I feel for these stupid doctrines, relics of medieval times, which survive to this day in most French provinces.

That was not the end of this painful ordeal. My mother had disappeared, taking refuge in a country house called le Chuzeau which we owned not far from La Côte. When the time of departure came, my father wanted to make with me one final attempt to get her to say farewell and withdraw her cruel words. We came to Le Chuzeau with my two sisters. My mother was reading in the orchard at the foot of a tree. When she saw us she got up and fled. We waited a long time, and followed after her; my father called her; my sister and I were in tears. But all in vain — I had to depart without embracing my mother, without getting one word, one glance from her, and burdened with her curse!…

(Memoirs, chapter 10)

![]()

Unless otherwise stated, the photographs reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in September 2008, and other images have been reproduced from postcards in our collection. © Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb. All rights of reproduction reserved.

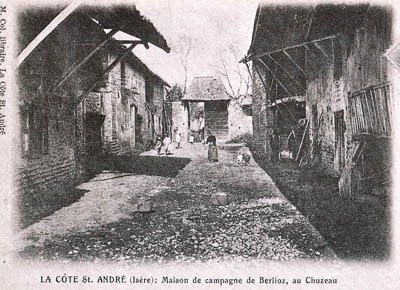

The Berlioz family farm at Le Chuzeau in the early 20th century

Today the courtyard of the farm, shown here in an old card from our collection, would be familiar to the Berlioz family as it has changed little since the early 19th century (see also the article by Antoine Troncy cited above).

The farm is now a heritage site.

The Pavillon “de la malédiction” in the late 19th century

The original copy of this water-colour painting by Jean Celle, dated 20 July 1895, is in the Musée Hector-Berlioz. We are most grateful to Madame Chantal Spillemaecker, Conservateur au Musée dauphinois and Conservateur du Musée Hector-Berlioz for sending us an electronic copy of this painting.

The Pavillon “de la malédiction” ca. 1959

The Pavillon “de la malédiction” – 2008

The Pavillon “de la malédiction” – 2008

The Pavillon “de la malédiction” – 2008

Official notice outside the farm

where the Pavillon is located –

The following photograph of the pavilion, taken in 2003, has been kindly sent to us by our friend Pepijn van Doesburg, to whom we are grateful.

![]()

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.