![]()

This page is also available in French

![]()

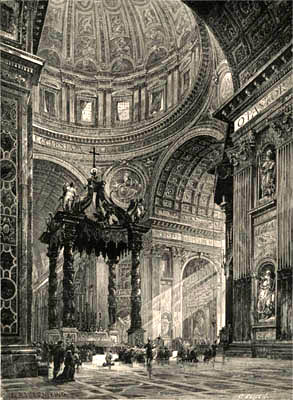

The origins of St Peter’s, the centre of the Roman Catholic faith, can be traced to the 2nd century, when a shrine was created on the site of St Peter’s tomb. The first great basilica, ordered by the Emperor Constantine was completed around AD 349. By the 15th century it was falling down. In 1506 Pope Julius II laid the first stone of a new church. It took more than a century to build and all the great architects of the Roman Renaissance and Baroque had a hand in its design.

Berlioz was not very impressed by Rome, for all its historical associations and monuments, with the exception of the Colosseum and above all St Peter’s. But he barely mentions them in the letters he wrote from Rome during his stay, and it is only in the accounts he published later that he allows his admiration to come through. Here in his own words is a glimpse of his experience of this magnificent edifice:

Saint Peter’s […] never failed to stir my admiration. It is so grand, so noble, so beautiful, and has such majestic calm! During the intolerable heat of summer I loved to spend the day there. I would bring a volume of Byron, settle comfortably in a confessional, and enjoy the cool atmosphere and awesome silence, only interrupted at infrequent intervals by the melodious ripple of the two fountains in the large square of St Peter’s which the breeze would convey to my ear. I would devour at leisure this ardent poetry and follow over the seas the Corsair’s audacious journeys. I adored this man’s character, at once inexorable and gentle, pitiless and generous, a strange blend of two seemingly contradictory feelings, hatred of humanity and love for a woman.

Occasionally I would put aside my book to meditate, and my eyes would wander around. Attracted by the light they would look up to Michelangelo’s sublime dome. What a sudden transition in thoughts! From the angry screams of the pirates and their bloodthirsty orgies, I would move suddenly to the music of the Seraphs, the peace of goodness, the infinite quietness of heaven… Then my thoughts would move down and delight in searching, on the square before the cathedral, the imprint of the noble poet’s steps…

(Memoirs, chapter 36)

I had hardly arrived when I made straight for St Peter’s… immense, sublime, overwhelming!… Here are Michelangelo, Raphael, and Canova. I am treading on the most precious marbles, the rarest of mosaics… This solemn silence… this cool atmosphere… these luminous tones, so rich and so harmoniously blended… This old pilgrim, kneeling alone in the vast edifice… A gentle sound, coming from the darkest corner of the cathedral, and rolling like distant thunder under these colossal vaults… I was frightened… I felt this really was the house of God and that I was not allowed to enter. On reflecting that weak creatures such as myself had nevertheless succeeded in raising this monument of grandeur and boldness, I felt a flush of pride. Then, thinking of the magnificent part that the art I cherished must be playing there, my heart started to beat at the double. Yes, I said to myself at once, these paintings, these statues, these columns, this gigantic architecture, all this is only the body of the edifice; music must be its soul; it is through music that it manifests its existence, it is music that sums up the unceasing hymn of the other arts, and with its mighty voice raises it incandescent to the feet of the Everlasting. But where is the organ?… The organ, slightly larger than that of the Opéra in Paris, was mounted on wheels; it was concealed from sight by a pilaster. No matter. This feeble instrument probably serves only to give the pitch to the voices, and should be adequate, if all instrumental effects are excluded. How many singers are there?… Recalling then the small hall of the Conservatoire, which could fit into St Peter’s fifty or sixty times over, I imagined that given a chorus of ninety voices for everyday use, the choristers of St Peter’s must have numbered in their thousands.

They are eighteen in number for ordinary days, and thirty two for solemn festivals. I have even heard a Miserere in the Sistine Chapel sung by five voices. […]

On one of those gloomy days which darken the end of the year, made even more dismal by the icy blast of the north wind, listen, while reading Ossian, to the extraordinary harmony of an aeolian harp placed on top of a bare tree. You might experience a deep feeling of sadness, a vague and boundless longing for another life, an immense loathing for this one – in short, a severe attack of spleen combined with a temptation for suicide. This effect is even more powerful than those of the choral harmonies of the Sistine Chapel. And yet no one has suggested including the makers of Aeolian harps among the great composers.

(Memoirs, chapter 39)

![]()

Unless otherwise stated, all the photographs reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in May 2007; other pictures have been scanned from engravings in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

The original copy of the first 3 engravings below have been donated by us to the Hector Berlioz Museum and they hold the copyright for them.

![]()

© Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.